This will be my 32nd winter in Kurohime, way up in the hills of northern Nagano Prefecture. Yesterday I was stacking firewood for the Afan Woodland Trust Centre, which has a fine, baronial-style stone-and-brick fireplace. There really is nothing like a room heated with firewood, and sitting by an open fire watching the logs burn is far more relaxing than television.

When I was a boy growing up in Britain, every house that I knew had a fireplace — in fact usually more than one, if not one in every room. In the country they usually burned wood, but in the towns the fuel was coal. Our coal was delivered in sacks by burly blokes with blackened faces who hefted them from a cart pulled by an enormous black Shire horse with a white patch on his forehead and white feathering on his front legs. Any dung that the horse dropped on the street was quickly gathered up by the residents for their gardens — my grandfather swore that horse dung was the best thing ever for roses.

But I digress. The coal those burly blokes tipped from their sacks into a small shed in the back (the "coal hole") was brought into the house in a large brass scuttle. Bringing in the coal, cleaning the fireplace and setting up the fire to be lit was my job — and of course I loved it, because I often got to light the fire and could then watch it catch hold as well.

Those coal fires, however, caused horrendous air pollution in the cities, especially in London and the industrial North, where it combined with the fog that figures a lot in British weather to create "smog." This often got so dense that you really couldn't see more than a few feet in front of you — and thousands of people with weak chests would die every winter.

So, though it was very nice to have a room heated by an open coal fire, it was wise of parliament to pass the Clean Air Act in 1956, as this banned those fires in most of Britain's towns and cities and also made factories stop belching black smoke out of their chimneys. However, wood fires were still allowed in the countryside, and I don't see them being banned in Japan either, especially as 67 percent of the country is covered with forests, woodlands and tree plantations.

Nonetheless, I do admit that wood fires in an open fireplace are not really efficient because a lot of the heat goes up the chimney. Wood stoves, especially catalytic ones, are far more efficient. With them, though, if you can see those lovely moving flames and glowing coals at all it will be through glass that's like as not smudged.

Despite this drawback, timber's future has been burning brighter this year, since 2011 was designated by UNESCO as its Year of the Forest. I served on Japan's national Year of the Forest committee, and throughout the year I've done quite a bit of traveling and study a lot about Japan's forests. Along the way I recently came across a very modern, highly efficient factory in Maniwa, Okayama Prefecture, that ought to douse any flickerings of doubt anyone might have about our forests having the potential to be a tremendous natural resource.

The name of the company is Meiken Laminated Wood Co., and its president, Mr. Koichiro Nakajima, was also on the Japanese Year of the Forest committee. His company's manufacturing process produces tons of bark, sawdust, shavings and odds and end of wood which they are turning into energy. Twelve years ago they brought in a steam-powered generator that cost so much that their accountants heaped scorn on management's decision as being a "waste of money."

Well, the bean-counters were proved wrong. Shredded bark is burned to heat water in a boiler that produces the steam to drive the generator. Moreover, before it is burned, the bark is itself dried using excess heat from the chimney, which makes it a much better fuel. The factory now produces nearly all the electricity it uses in the day when the equipment is working flat out, while during the night when the factory is almost idle the company sells its excess electricity — which provides enough power for 2,000 households.

As well, seven years ago Meiken began to use wood shavings and sawdust to make wood pellets for stoves. It now produces and sells 13,000 tons a year of this easily used, easily transported fuel. I noticed that the freshly compressed pellets were very hot, so diseased timber would be sterilized by this process — which is an important factor for foresters having to cut down large numbers of trees in order to deal with fungal infections.

Meanwhile, from aromatic trees such as cypress, Meiken is also making a range of clear, fragrant oils that are extracted from wood chips destined to become paper — a process that doesn't alter the quality of the paper. The oils can be used in numerous ways, including in detergents and liquid soaps.

At present, the only waste from Meiken's production processes is ash. Burning wood produces from 6 to 10 percent ash by weight, and if properly used this makes an excellent fertilizer rich in calcium, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, aluminium and many micronutrients essential for plant growth. On acid soil it can also be used instead of lime.

However, the giant agricultural co-operatives of Japan are not in the slightest bit interested in trying anything "new," and prefer to go on pushing fertilizers made from petrochemicals — all of which is, of course, imported. Wood ash is a problem to transport and store, but these problems can be solved, especially if you use the stuff locally.

Most country folk (us included) recycle wood ash to the soil, whether it be in our gardens or in the woods. If the compost tub gets smelly I toss in some wood ash that both cuts down the smell and keeps away flies. It also seems to hasten decomposition.

At the Meiken factory, although wood ash is at present a waste product, Mr. Nakajima is a persistent fellow, a visionary, and I have no doubt he'll find some agricultural group to work with eventually.

In yet another woody vein this year, I am delighted that Dr. James Foster, an old friend and a computer expert, has recently moved to Kurohime from Tokyo, together with his Japanese wife, one of his two daughters and Leo, his German shepherd dog. Today I helped him shift two K-truck (as those little white trucks seen all over Japan's countryside are called) loads of well-seasoned firewood from my basement to his house. I thought that was the very best of housewarming gifts. I've already given him some good, well-aged single-malt whisky, so no doubt we will use both to warm ourselves when the winter snows come.

Tonight, we have one of our "boys night" gatherings at our Trust Centre. That big baronial fire will be lit in the main hall, and everybody will bring something — whether bottle, plate or pot — and my contribution will be a venison stew fit to feed 20 that I've made with lots of potatoes, carrots, leeks, parsnips and winter mushrooms (all home-grown). We have checked our mushrooms especially, both shiitake and nameko (the yellow winter ones), for radioactivity and they are just fine, which is a relief.

Astonishingly, though, even yesterday some people came from Tokyo to do an interview and they asked why I live in the country. Why do I have to go over the same things time and time again? Is it impossible to envisage that a former foreigner (I'm a Japanese citizen) would prefer to live a rural life? I feel sorry for folk who are tied to a city, with expensive land, poor air, too many cars and people — and with great ugly buildings blocking out the sky. Wasn't it Mark Twain who wrote that clever people live in a city, but wise men live in the country?

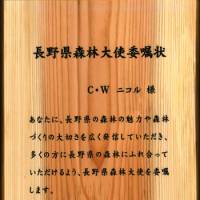

Forest Ambassador

At an open ceremony held in the Aeon shopping center in Ueda City, Nagano Prefecture, on Nov. 23, Nagano Governor Shuichi Abe appointed C.W. Nicol to be the prefecture's first-ever Forest Ambassador.

A certificate to this effect, inscribed in black ink on a board of cryptomeria (sugi) wood, was presented to Nicol, after which short speeches were made and officials from both the prefecture's and the central government's forestry agencies engaged in a round-table forum.

The small crowd of people gathered for the ceremony heard that almost 80 percent of Nagano is covered with trees, and that nationwide it ranks third (after Hokkaido and Iwate) in forest area — but in timber production Nagano is a mere 19th among Japan's 47 prefectures.

With this lowly ranking adding urgency to his forestry drive, of which Nicol's appointment is part, Gov. Abe said he hopes to rejuvenate the industry in Nagano by improving woodland management and the use of forest resources — to which end he was handily able to remind his audience of an exhibition of wood-pellet heating stoves on the roof of the shopping centre.

The governor also spoke of the need to improve forest access in order to reap the rewards of a growing trend toward eco-tourism. Narrow logging roads, he pointed out, can also be used for hiking, cycling and cross-country skiing, to name just a few activities.

To this list, Nicol — who expressed his delight and honor at being appointed to foster "such vital issues for Nagano" — added the uses of woodlands as places of healing, a movement he instigated in his hometown of Shinanomachi (Kurohime), in Nagano, and which is fast gaining in popularity.

Besides his new role as Nagano's Forest Ambassador, Nicol is also on the Japanese committee for UNESCO's Year of the Forest (2011). The C.W. Nicol Afan Woodland Trust has been designated by UNESCO Japan as a Heritage Site for the Future. Nicol is a Welsh- born Japanese citizen. (Andrew Kershaw)

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.