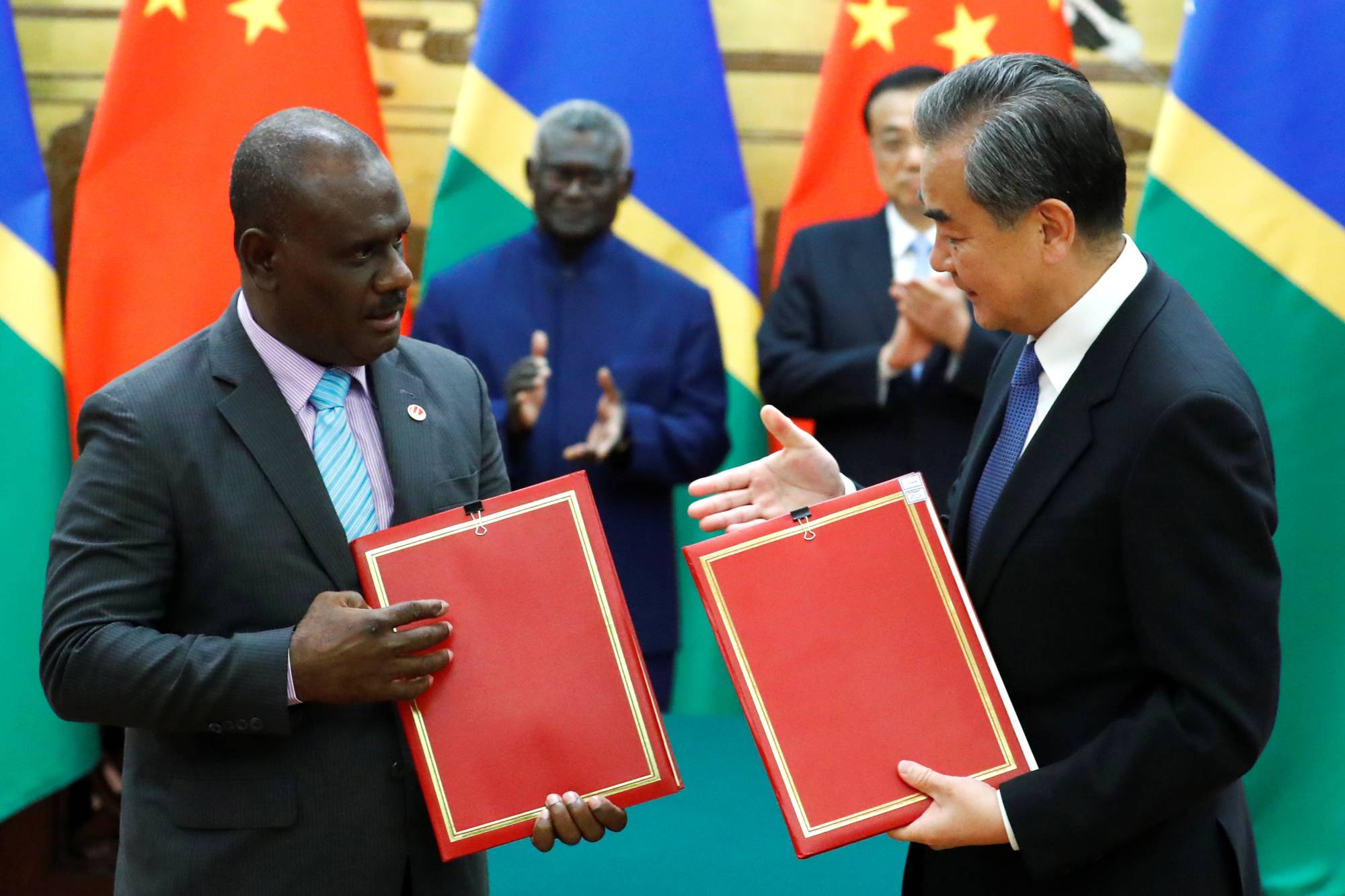

The leak of a draft security cooperation agreement between China and the Solomon Islands has alarm bells ringing in Honiara, the nation’s capital, and beyond.

Provisions in the agreement, such as those that seemingly authorize the dispatch of Chinese forces to help control social unrest in the country, are especially worrisome.

Rather than complain, governments that are troubled, and Tokyo is among them, should pay more attention to local concerns. South Pacific nations are threatened by climate change and diminishing economic opportunities. They fear becoming pawns in the geopolitical competition between China and the West. Governments that fear Chinese encroachment should do more to address the issues that worry their residents to win favor in regional capitals.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.