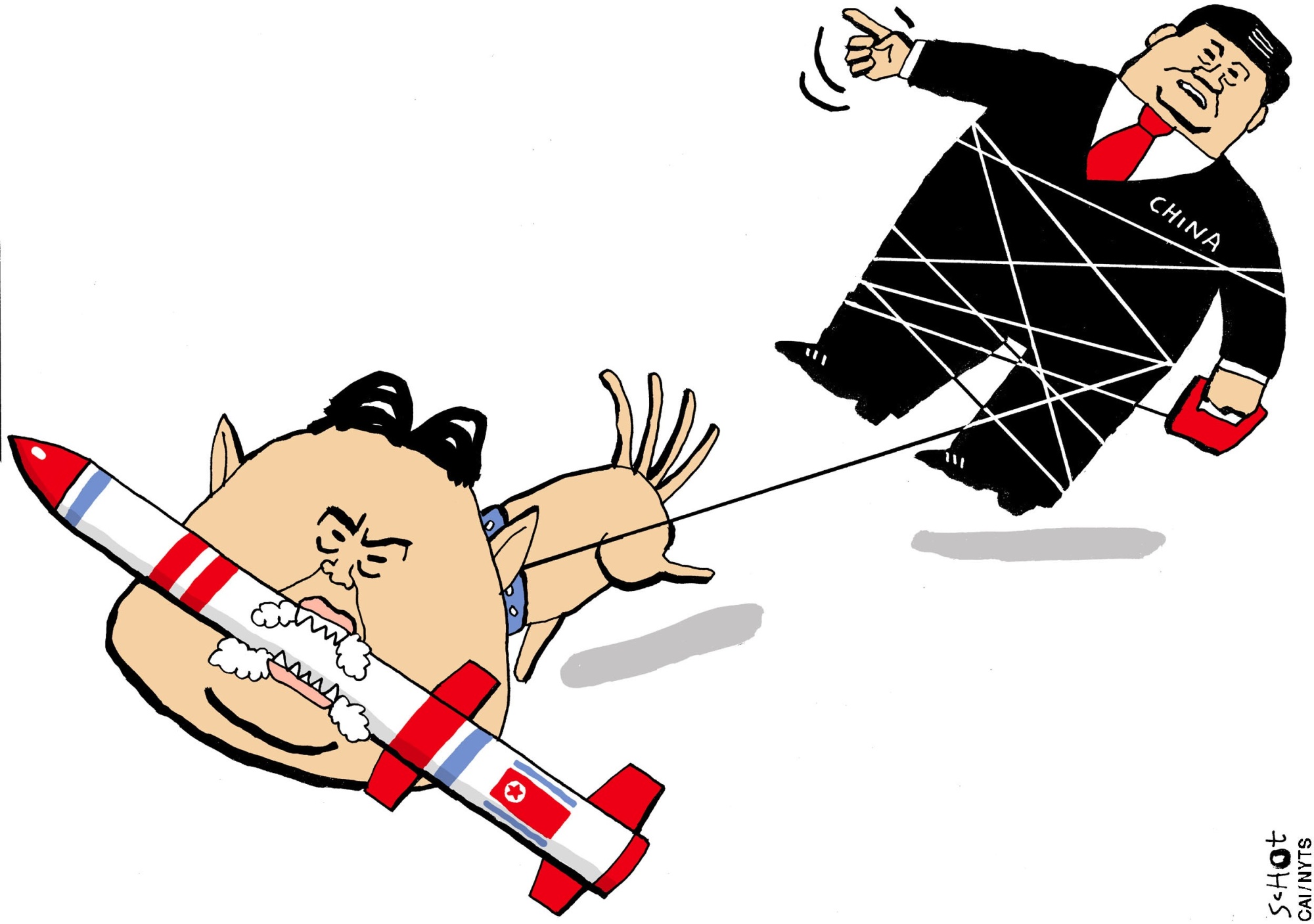

The idea that China holds the key to solving the ongoing political and military crisis on the Korean Peninsula has been the standard jack-in-the-box of U.S. North Korea policy for the past seven decades, set to pop up whenever U.S.-North Korea tensions escalated and the threat of war thought imminent.

U.S. President Donald Trump and former Chief White House Strategist Stephen Bannon are only the latest to espouse the view that China has the power and influence to induce its "client state" to stop its saber-rattling and nuclear provocations. (This view is not just confined to U.S. policymakers, either.) In fact, ever since Chinese troops crossed the Yalu River on Oct. 1, 1950, and attacked U.S. and U.N. forces on North Korean soil, numerous U.S. policymakers have been looking to Beijing as the eminence grise of the Kim dynasty that can sway the latter's behavior.

Indeed, despite substantial evidence that the incumbent North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un, has a strained relationship with his big neighbor and has been openly antagonizing the communist leadership in Beijing as well as deliberately curtailing Chinese influence in his country, the "client state" narrative continues to hold sway. However, this narrative decidedly runs counter to the deep historical sense of mistrust between the two nations.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.