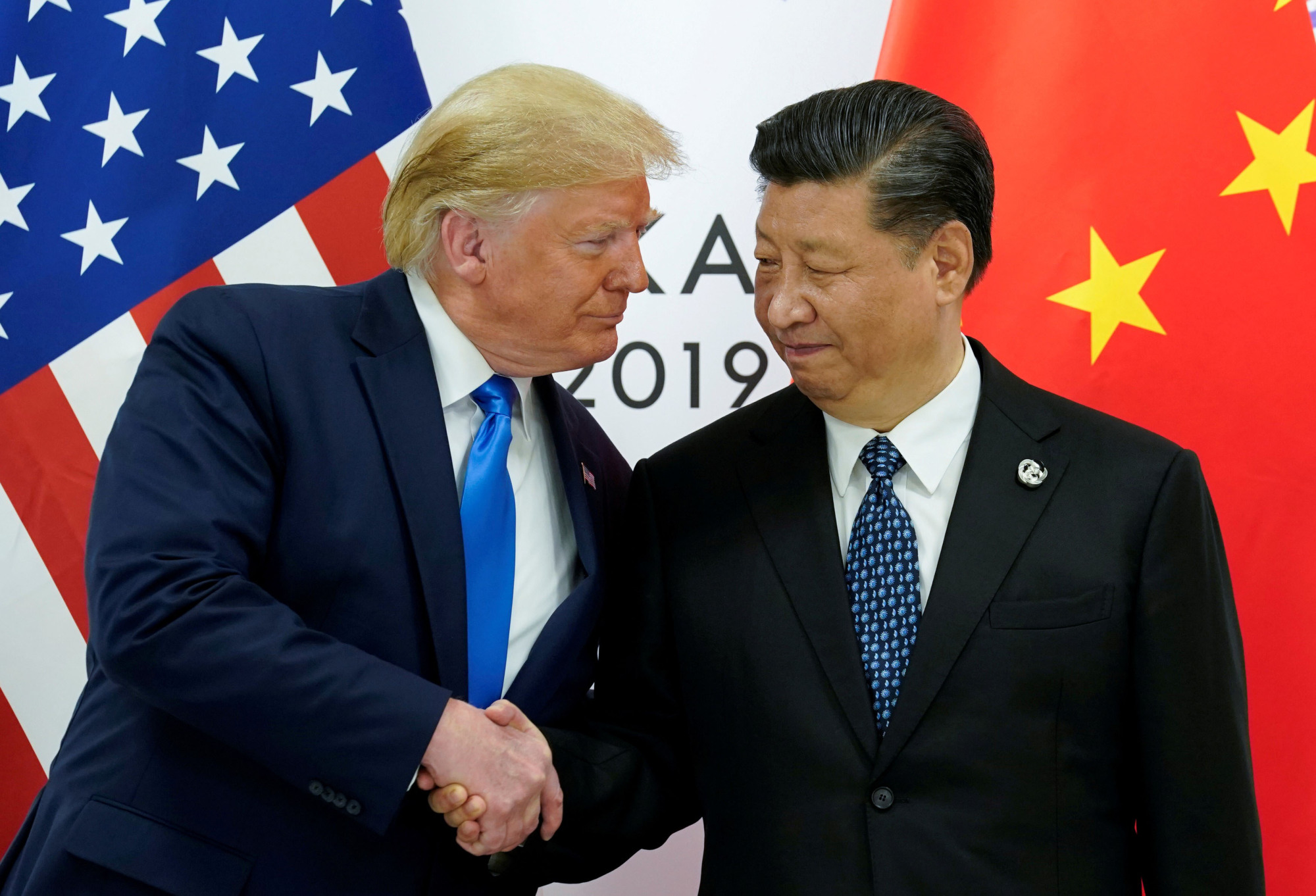

Relief that Presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping came to a trade truce will likely be short-lived. That's because the two men have less command over the forces shaping global commerce than they might like to think.

The decline of trade and manufacturing began in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, long before either leader came to power or tariffs started volleying between Washington and Beijing. The trade war has harmed confidence, but it's just a sideshow to the deeper underlying currents in the global economy, which is driven by the ebb and flow of credit.

On the surface, the weekend agreement to resume talks may have put a floor under sentiment. It didn't alter the world's short to medium-term landscape: The U.S. expansion has just become the longest ever, though few are carousing; China is in a long-term slowdown with short-term pain points; and Europe is wobbling. For the past decade, inflation has been quiescent almost everywhere, and markets are still looking to central banks to save the day. The idea that the pomp and ceremony of a Group of 20 meeting will reshape the world economy is a fallacy.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.