At this shank end of a summer that a calmer America someday will remember with embarrassment, you must remember this: In the population of 325 million, a small sliver crouches on the wilder shores of politics, another sliver lives in the dark forest of mental disorder, and there is a substantial overlap between these slivers. At most moments, 312 million are not listening to excitable broadcasters making mountains of significance out of molehills of political effluvia.

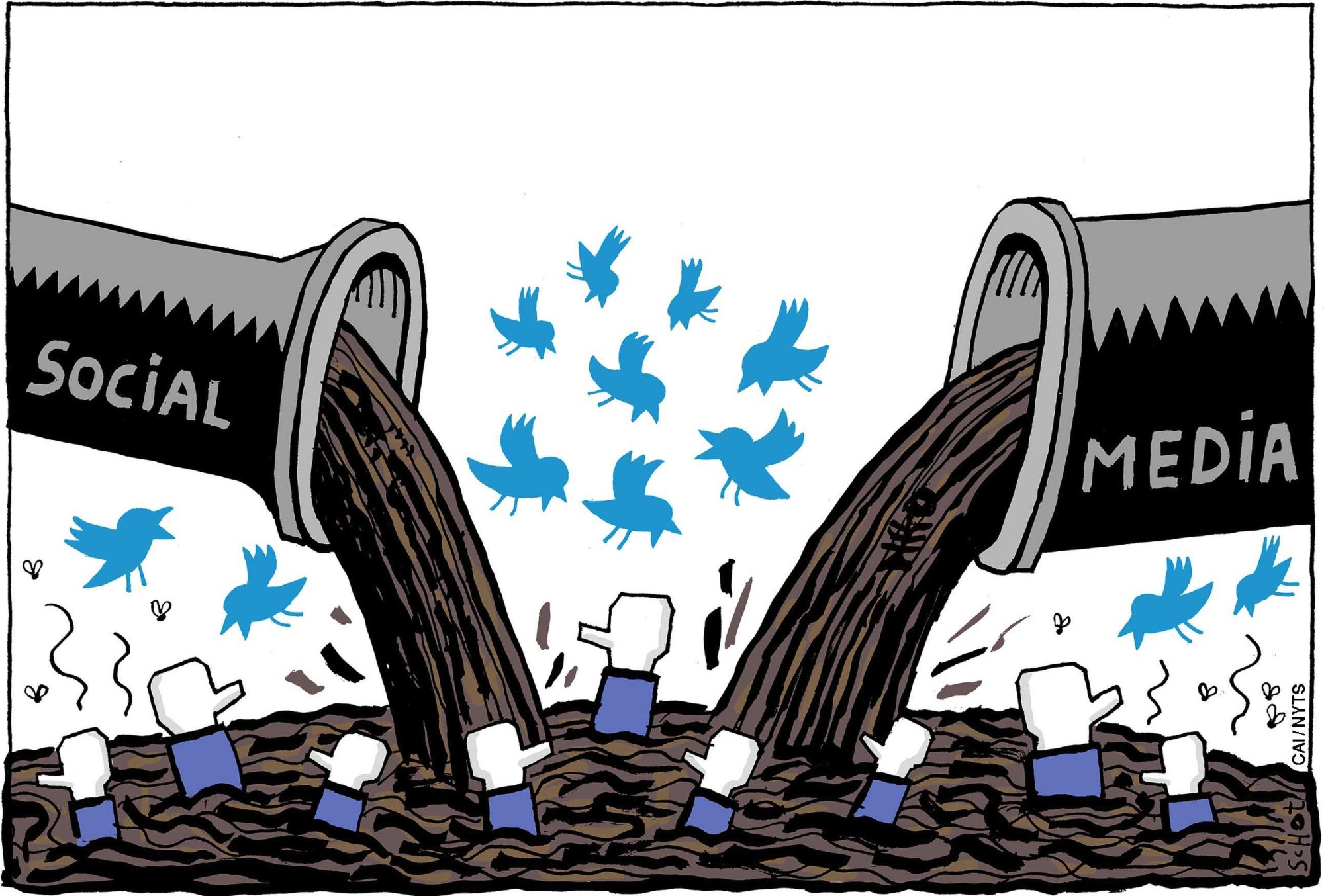

Still, after a season of dangerous talk about responding to idiotic talk by abridging First Amendment protections, Americans should consider how, if at all, to respond to "cheap speech." That phrase was coined 22 years ago by Eugene Volokh of the UCLA Law School. Writing in The Yale Law Journal ("Cheap Speech and What It Will Do") at the dawn of the internet, he said that new information technologies were about to "dramatically reduce the costs of distributing speech," and that this would produce a "much more democratic and diverse" social environment. Power would drain from "intermediaries" (publishers, book and music store owners, etc.) but this might take a toll on "social and cultural cohesion."

Volokh anticipated today's a la carte world of instant and inexpensive electronic distributions of only such content as pleases particular individuals. Each person can craft delivery of what MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte called (in his 1995 book "Being Digital") a "Daily Me." In 1995, Volokh said that "letting a user configure his own mix of materials" can cause social problems: customization breeds confirmation bias — close-minded people who cocoon themselves in a cloud of only congenial information. This exacerbates political polarization by reducing "shared cultural referents" and "common knowledge about current events."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.