The mouthwatering scent of boiled bonito broth fills the room — an aroma akin to that which is released from dashi, the simple yet savory culinary cornerstone of Japanese cuisine, and the soup stock responsible for bringing out the umami in our food.

Except, this isn’t a washoku restaurant.

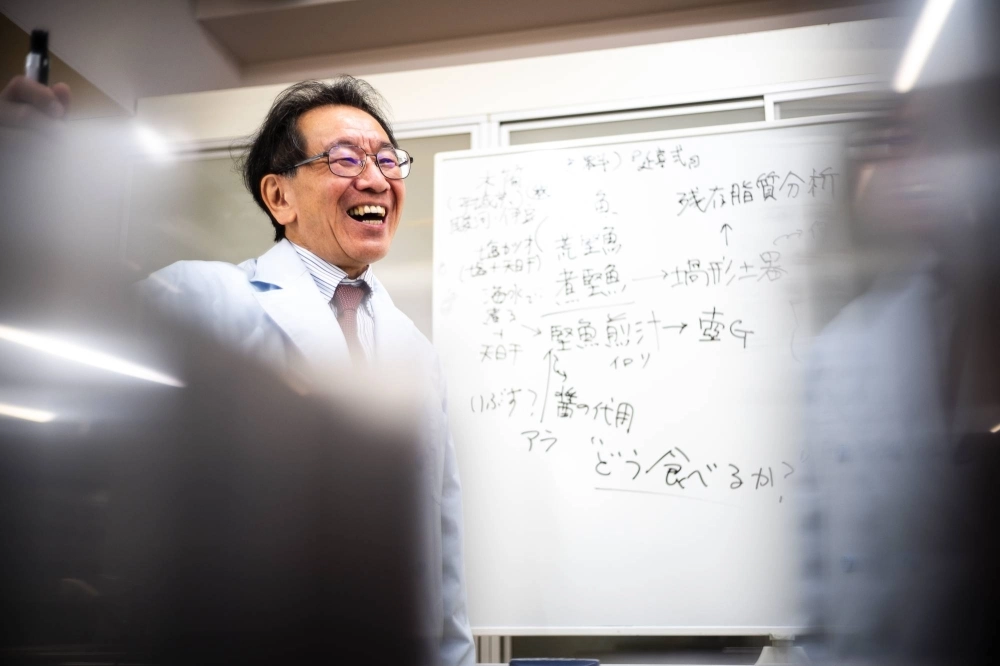

Instead of chefs and wait staff, there’s a group of furrow-browed researchers in white lab coats standing around a steel pot sitting atop a stove. They’re timing how long the liquid in the pan has been bubbling over the fire.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.