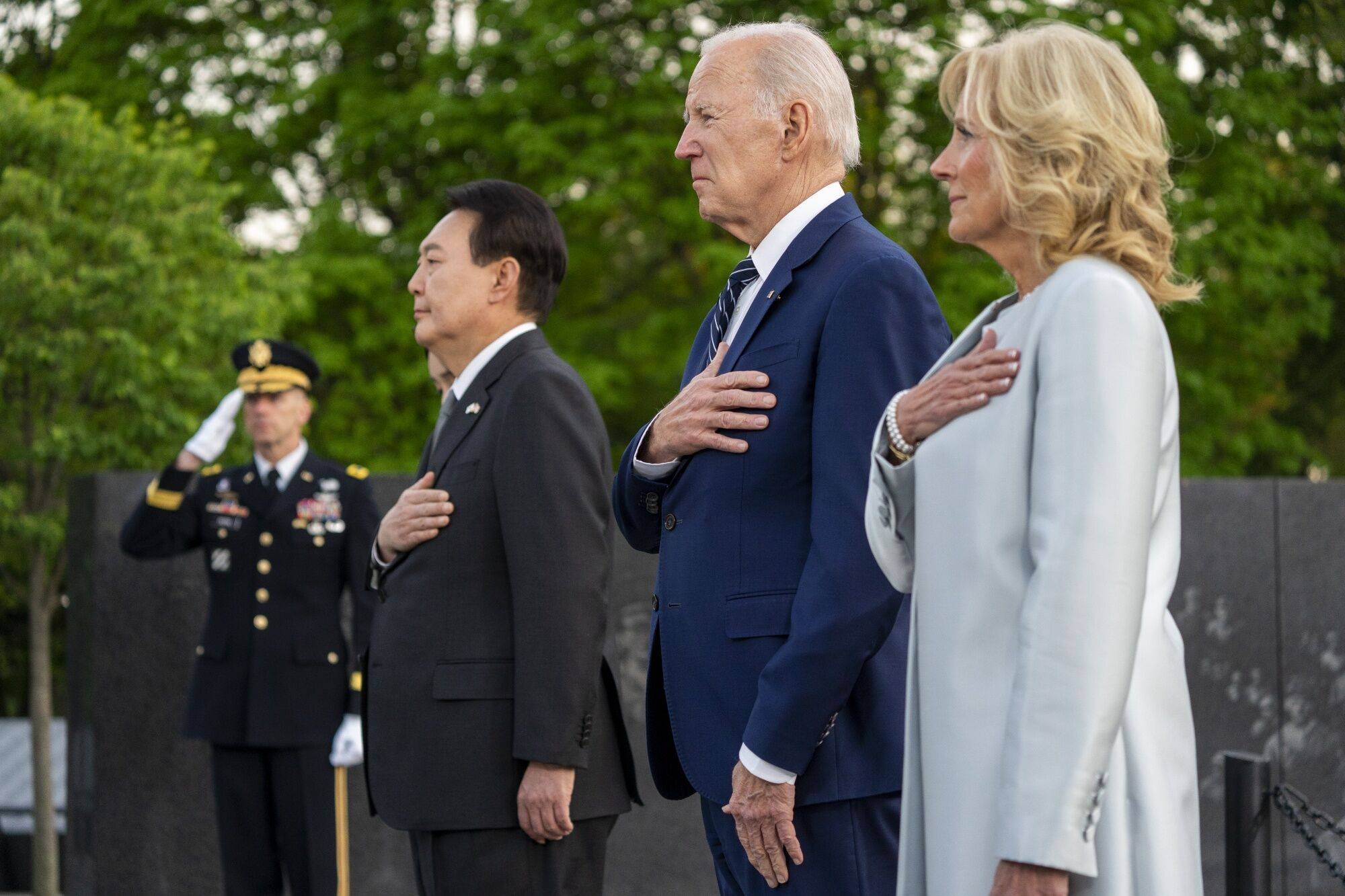

South Korea will make clear on Wednesday that it will not seek its own nuclear weapons, as President Yoon Suk-yeol meets with U.S. leader Joe Biden in Washington amid growing concerns in Seoul over the United States' commitment to defending its Asian ally from North Korea’s increasingly potent missile and nuclear arsenal.

The pledge will be part of a new agreement — known as the Washington Declaration — that also creates a fresh bilateral nuclear consultation mechanism based on U.S.-European Cold War-era frameworks, according to senior U.S. officials, who said the document had been under discussion with Seoul “for months.”

Once a fringe position, support for the idea of South Korea developing its own nuclear bombs has spread rapidly in the country as doubts grow about the United States’ willingness to potentially sacrifice San Francisco for Seoul, after North Korean nuclear and missile breakthroughs have put American cities firmly within striking distance.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.