"Let's dance!" If the late David Bowie had sung his 1983 smash hit in Japanese, he would have made it 踊りましょう (Odorimashō) or, in plain style, 踊ろう (Odorō).

And if the makers of the Japanese 1996 box-office hit "Shall we Dance?" had gone for a native title — no doubt they had good reasons not to — they might have used the same form with a question marker, making it 踊りましょうか (Odorimashō ka) or 踊ろうか (Odorō ka). No need for "let's" or "shall" or anything else, because Japanese verbs come factory-equipped with a special inflection just for such types of invitations and encouragements.

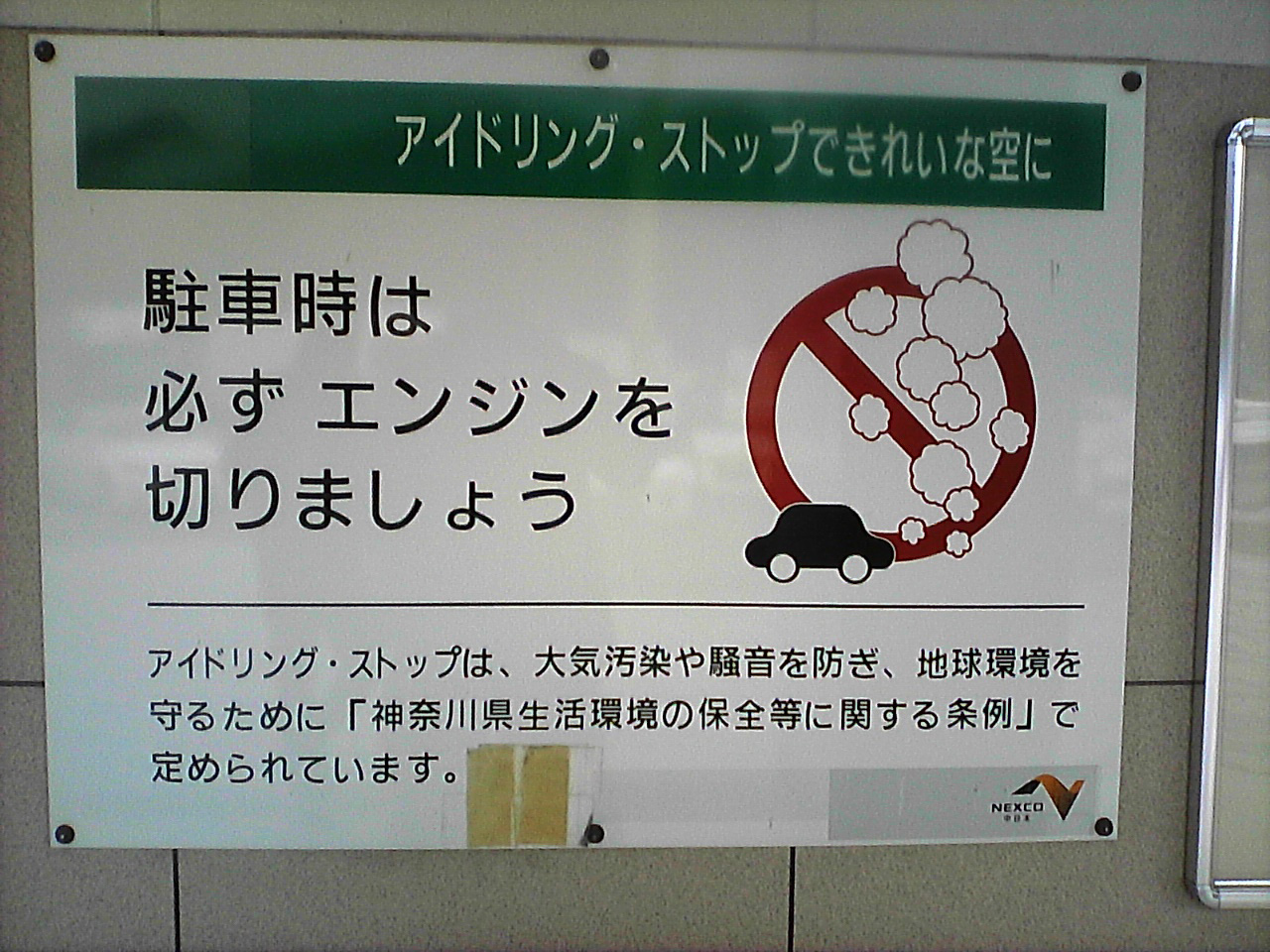

All of these ōs and shōs, and their English counterparts, fall into the group of what linguists call "hortatives" — forms intended to encourage someone to do something. A somewhat confusing point about Japanese hortatives is that it is not always clear who exactly that someone is. As with the English "let's," the default assumption is that both the speaker and the hearer are included in the encouragement. So when wife says to husband 帰りましょう (Kaerimashō, "Let's go home"), she (a) wants to leave and (b) wants him to leave too. Or think of the popular nursery rhyme with the chestnut tree that goes 仲良く遊びましょう (Naka yoku asobimashō, "Let's play nicely together"). Everyone who knows the full lyrics (no showing off — it's only four lines) will also know that both あなた (anata, you) and 私 (watashi, I) are explicitly part of this invitation.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.