“Still Alive”: The two short words that serve as the overall theme of this year’s Aichi Triennale suggest a mountain of meaning. They could be a provocation, after a statue symbolizing wartime “comfort women” sparked controversy at the 2019 triennale and, after a torrent of threats and complaints, was temporarily shut down. Or they could be an expression of hope, after a three-year period in which the global pandemic turned cultural gatherings into public health risks. Or they could be a more primal declaration.

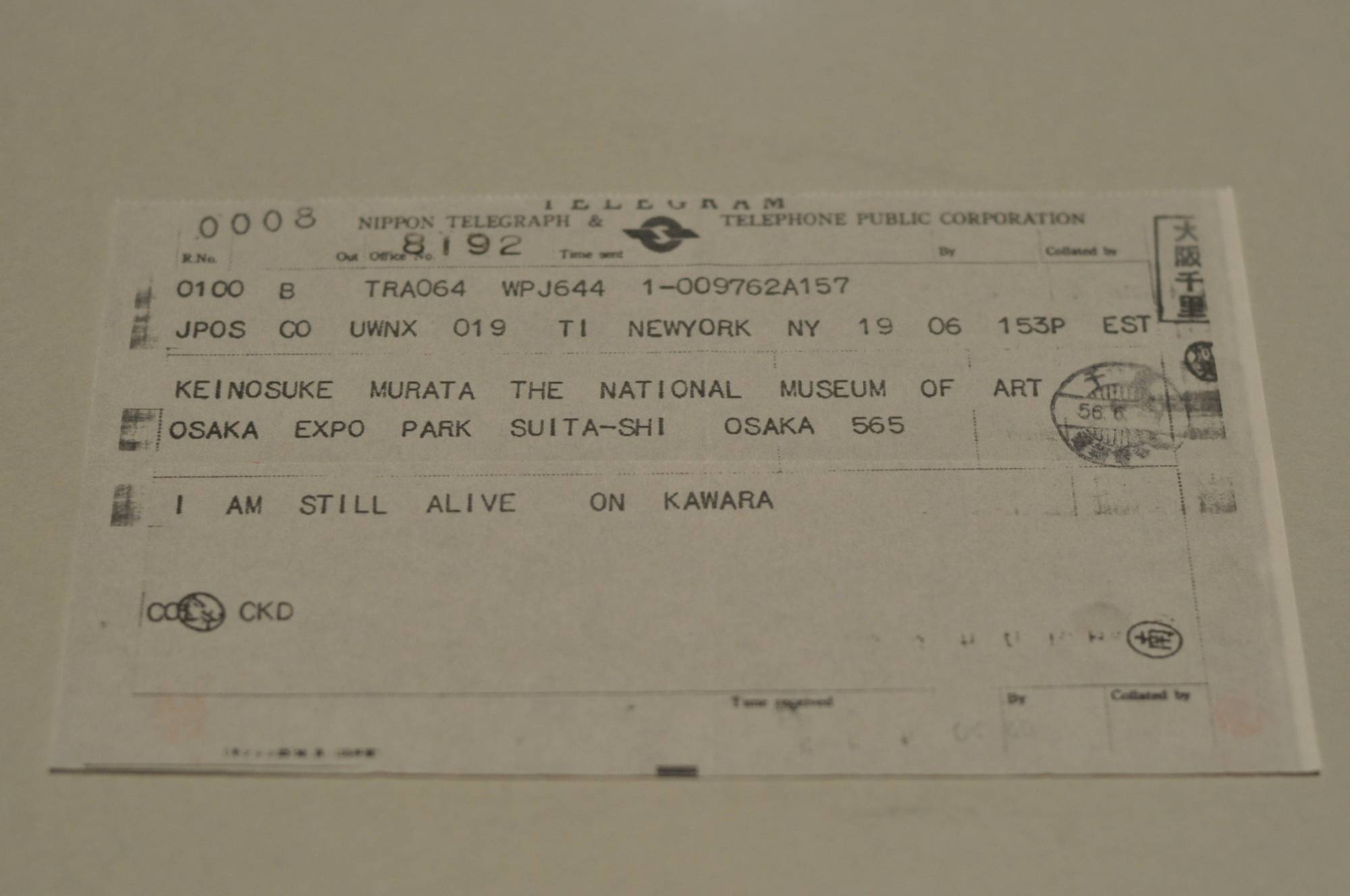

That’s also true of the work that inspired the theme, on view at the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya through Oct. 10. Conceptual artist On Kawara’s “I Am Still Alive” is a series of roughly 900 telegrams sent over 30 years with variations on that basic sentiment. He initially sent three messages in 1969: “I am not going to commit suicide don’t worry”; “I am not going to commit suicide worry”; and “I am going to sleep forget it.” The subsequent 30 years of telegrams, with the simpler message, “I am still alive,” became a new series and, ultimately, a moving piece of conceptual art. The implication is this: If there was any reason to think the artist might no longer exist, here was affirmation of his life.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.