"Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow,” Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida recently told an international security gathering in Singapore, a catchphrase that speaks to the harsh lessons learnt over the past few months.

Better deterrence and response capabilities, he told a room packed with defense officials and diplomats, will be "absolutely essential if Japan is to learn to survive in the new era and keep speaking out as a standard-bearer of peace.” Cranking up rhetoric, though, is the easy part.

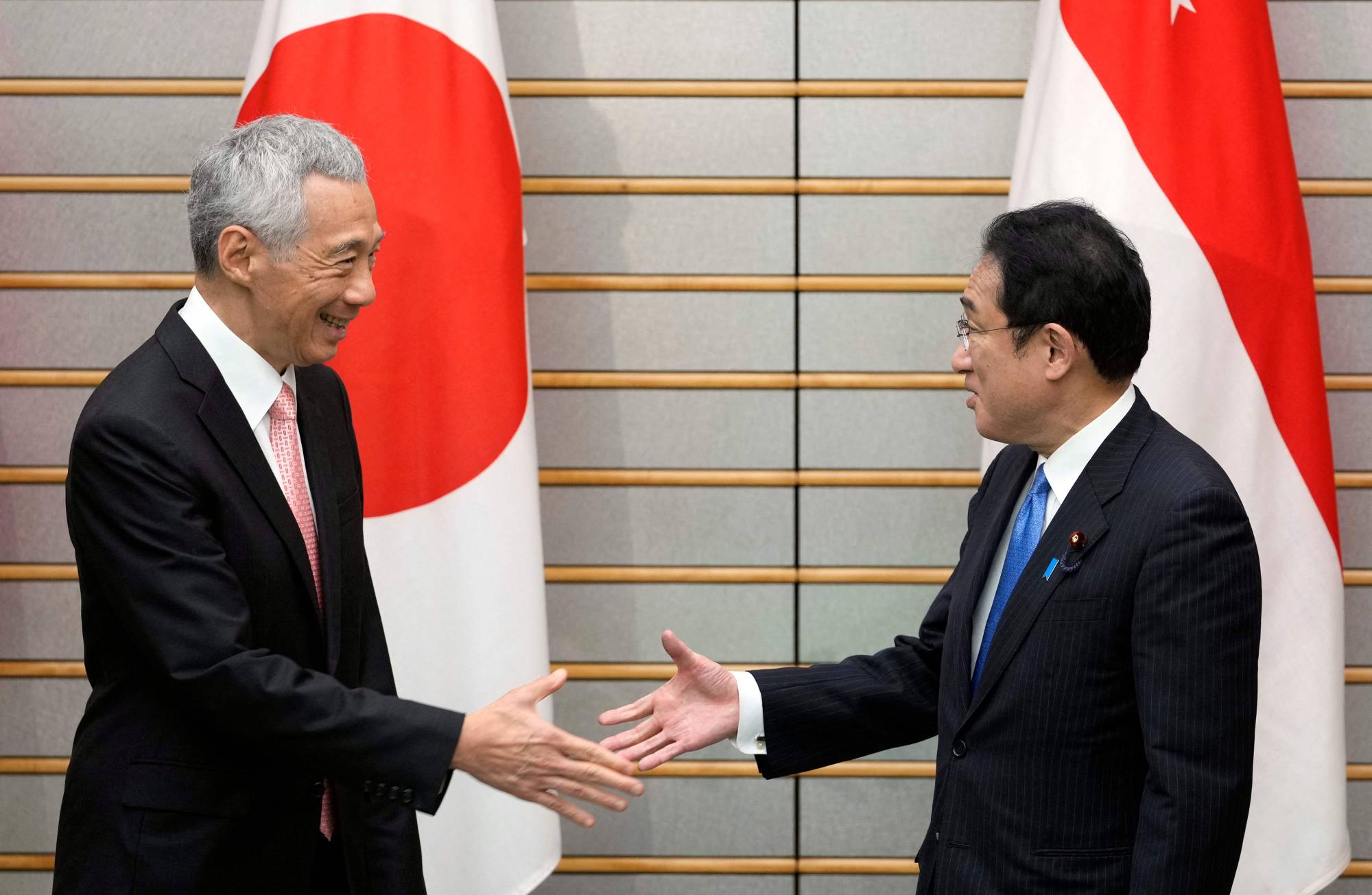

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has jolted the pacifist nation into making bigger promises on spending, security and a foreign policy that relies on more than economics — welcome news for allies eager to have a muscular Japan discouraging provocations from its nuclear-armed neighbors. Tokyo now needs to overcome what remains of domestic resistance, free up funds and strengthen alliances, and fast. But this "courteous power” can already use diplomatic tools to do more for the "rules-based free and open international order” that Kishida talked up at the Shangri-La Dialogue earlier this month. He could do worse than to start in Southeast Asia. It’s a region that, like much of the emerging world, has largely distanced itself from allies’ response to President Vladimir Putin’s aggression — and where Japan has more credibility than most.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.