Fifty years have passed since U.S. President Richard Nixon’s February 1972 visit to China.

Nixon’s visit achieved the normalization of U.S.-China relations, drove a wedge into the Sino-Soviet relationship and established a foothold for extricating the U.S. from the quagmire of the Vietnam War.

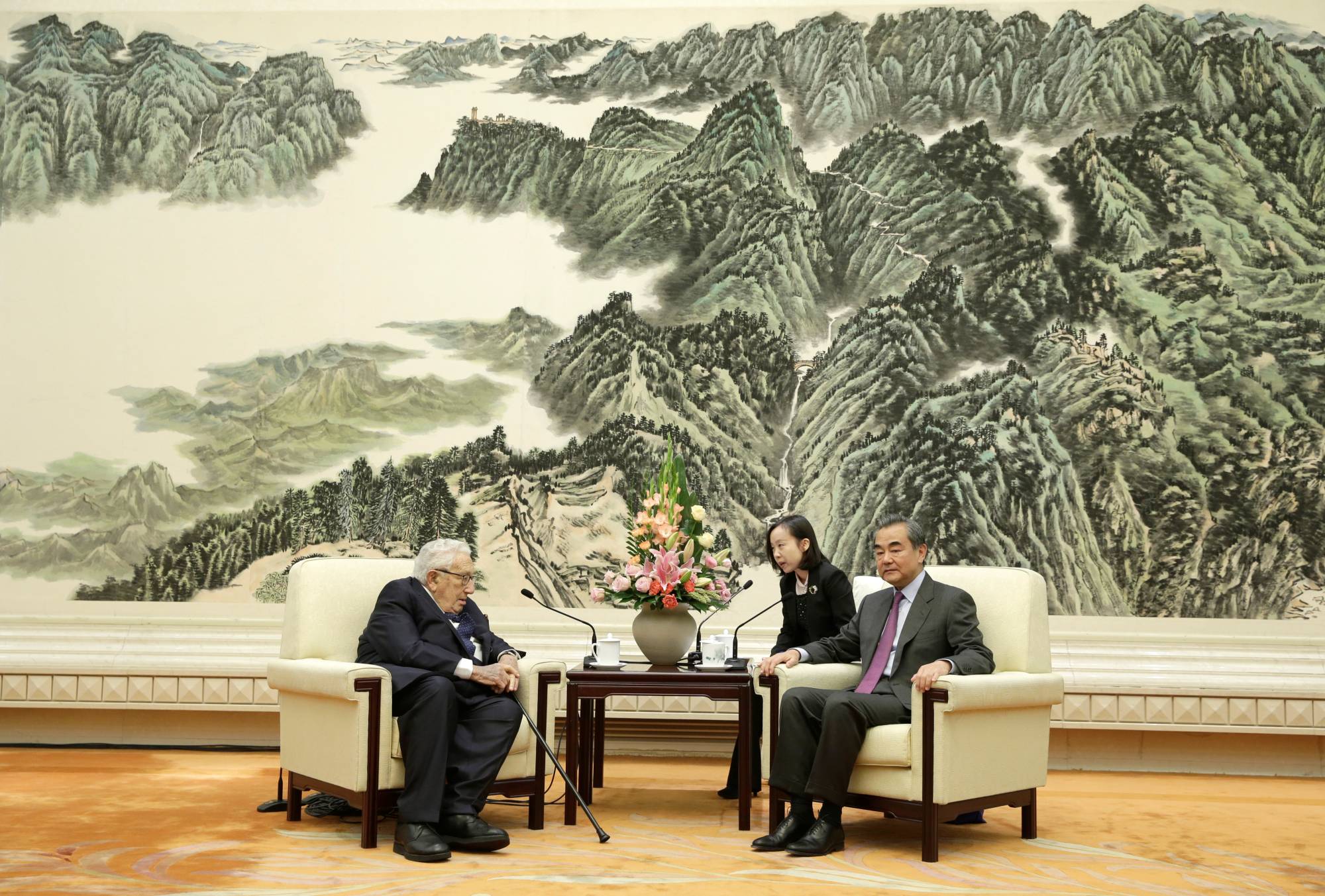

The visit was a diplomatic feat by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.