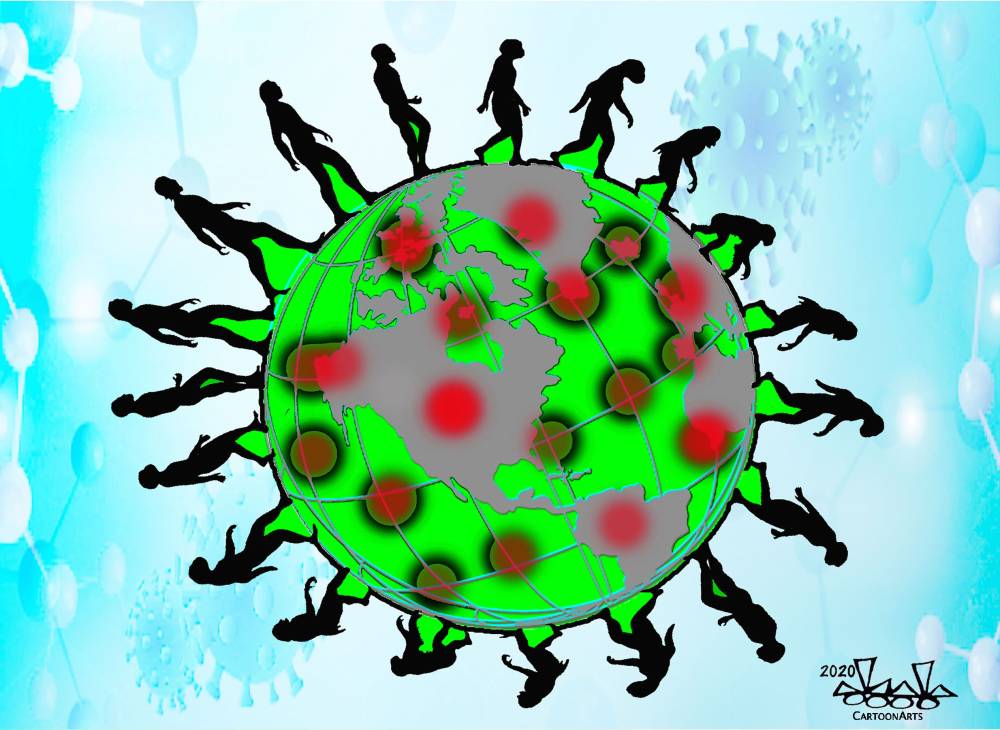

Crises are not just tests of leaders. They are also tests of ideas about how the world works. The coronavirus pandemic is helping bring one such idea — the concept of realism — back into vogue, by reminding us that we still live in a world where cooperation is hard, self-interest predominates and globalization is no magic elixir. Yet the current crisis is also demonstrating that this venerable intellectual tradition has enormous blind spots, and that a dog-eat-dog ethos isn’t so realistic after all.

Realism is a body of thought reaching back to Thucydides, but it emerged most fully in the 20th century as a response to two world wars and the vicious international insecurity that caused them. Although there are many varieties of realism, the bedrock principle is that world politics are a cutthroat affair. States must look after their own interests because there is no overarching authority to protect them. Moral and legal norms count for little; the “global community” is an illusion; trade is no guarantee of peace. Power is what matters most in an anarchic world and the penalties for weakness are severe.

Realism took a beating after the Cold War, when the importance of geopolitics seemed to recede and there were hopes that globalization was drawing the world into single community. But it has experienced a revival more recently as sharp international rivalry has returned. The Trump administration described its America First national security strategy as “principled realism.” And as advocates of realism have argued, the coronavirus has — in certain respects — affirmed that concept’s underlying logic.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.