Dear Alice,

I'm looking at my Japanese driver's license and wondering if the form on the back has anything to do with organ donation. Years ago, I registered in the United States to be an organ donor, which was a simple matter of checking a box on my driver's license application. Now that I'm living in Japan, I'd like to register here too, but have no idea how the heck it's done. Can foreigners be donors? Actually, I'd prefer to offer the whole kit and caboodle, but is it possible in Japan to donate one's body to science?

Gregory H., Saga Pref.

Dear Gregory,

Let's look at this one part at a time. In Japanese, the term for organ donation is zōki teikyō. Japan works on an "opt in" or "explicit consent" (meiji no dōi) model, which means that you have to take a concrete action, such as filling in a form, to declare your willingness to be a donor. This is different from some countries, including Spain and Austria, where everyone is presumed to be a willing donor unless they take action to register their refusal. Fortunately, the process to "opt in" is relatively easy in Japan and can even be done in English.

Foreign residents are welcome and encouraged to become donors, and while the nationality of donors is neither disclosed nor recorded, there have been cases in which a foreigner died and provided organs to save the lives of others, according to Misa Ganse, director of operations at the Japan Organ Transplant Network (JOT).

At present, there are nearly 14,000 people in Japan on the waiting list for an organ, with kidneys (jinzō) being the most needed. But because there are so few donors here, most of these patients will die while waiting for an organ that could save their lives. Some Japanese travel overseas, at crushing costs, in order to receive an organ transplant. This is a controversial practice since no country has a surplus in organs.

In the United States, where organ transplantation is better accepted, there are 7,000 to 8,000 organ transplants every year, which works out to about 26 organ transplants per million population. Contrast that to Japan, where the rate is just 0.9 transplants per million, the lowest rate in the industrialized world. Fewer than 100 organ transplants (zōki ishoku) were performed in Japan last year.

So what accounts for this low rate of donation? One factor is the traditional belief that a body should be whole upon cremation, but legal obstacles and some troubling history have also played a role. When medical advances made organ transplantation possible, during the 1950s and 1960s, Japan was on par with other countries or even ahead. Then an incident in 1968 brought developments here to a standstill.

That year Juro Wada performed the first heart transplant in Japan at Sapporo Medical University. Although the patient survived for 83 days, which was a very good outcome in those early days of heart transplantation, Wada came under intense fire. Critics charged that the operation was highly improper, if not downright criminal, particularly because the surgeon himself made the determination that the donor was brain dead. At the time, the concept of brain-based death (nōshi) was still new and there was no consensus in Japan on how to define it. Criminal charges against Wada were eventually dropped, but the public was left with a deep distrust of organ transplantation.

It took several decades after that to enact a law defining brain death and making it legal to transplant organs from brain-dead patients. More people now understand that it is possible for the heart to keep beating and the body to remain warm, even after the complete and irreversible loss of brain function. Public opinion polls now show an increase in willingness to donate after brain death — in a 2013 survey, 43.1 percent of respondents indicated that they would be willing to donate organs after brain death, while 23.8 percent remained opposed.

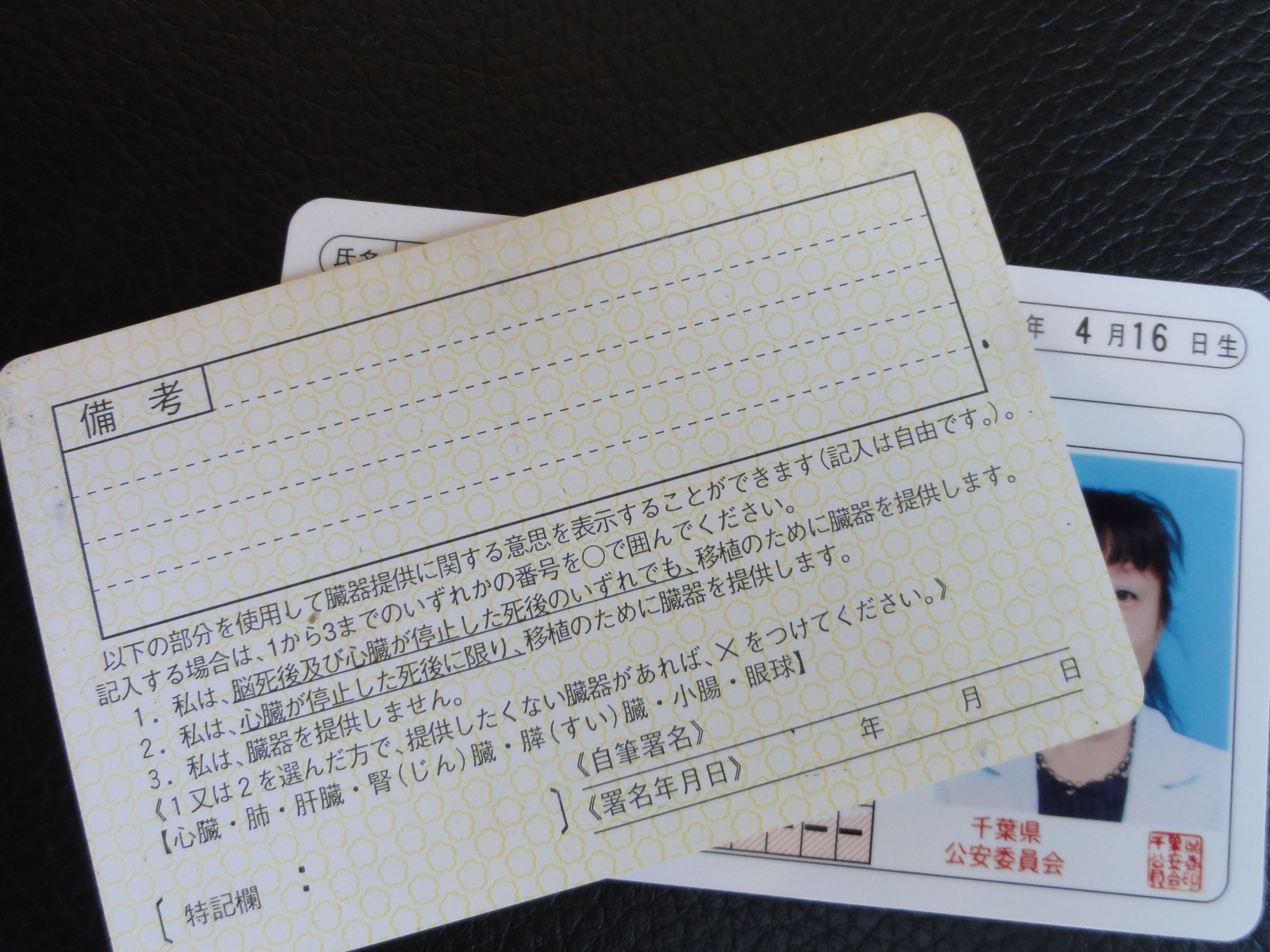

So let's go back to your driver's license. By completing the form on the back, you can declare your willingness to be a donor, and under what circumstances, or record your opposition to donating organs at all. For those who don't drive, the same form is on the back of Japanese health-insurance cards. It's also possible to record your wishes on a separate organ-donation decision card (zōki teikyō ishi kado), which can be picked up for free at municipal offices and some pharmacies. An English-language card can be downloaded from www.jotnw.or.jp/english/img/card-back3.pdf.

Let me explain the instructions, which are the same for both the Japanese and English versions. If you circle "1," you are consenting to nōshigo zōki teikyō (organ donation following brain death) as well as shinteigo zōki teikyō (donating after cardiac death). Circling "2" indicates you consent only to donation after cardiac death, and if you circle "3," it means you do not wish to donate at all. Placing an "X" over any of the organs listed — heart, lungs, liver, kidney, pancreas, small intestines or eyes — means you do not wish to donate that organ. It's a good idea to discuss your wishes with a family member, and get their signature next to yours. Family members always have the right to refuse donation, and if your wishes aren't clear, the law now allows family members to make a decision in favor of donation. Discussing your wishes in advance increases the chance that they'll be followed.

It is possible in Japan to donate your entire body to science, which is called kentai, but as in other countries, you can't donate organs and leave the rest of your body for medical training and research. Furthermore, donating your body has to be arranged directly with a medical school and there's no guarantee they'll take you when your time comes. At the moment, perhaps because some people see whole-body donation as a way to avoid the high cost of cremation in Japan, there's a national oversupply of cadavers.

For more on this topic, including helpful links, please visit my blog at alicegordenker.wordpress.com. On Sept. 10, I'm speaking at the College Women's Association of Japan (CWAJ) luncheon in Tokyo. Everyone is welcome. See www.cwaj.org/LuncheonPrograms/monthlyluncheon.html. Puzzled by something you've seen? Send a description, with a photo if possible, to [email protected] or Alice Gordenker, L&C Department. The Japan Times 4-5-4, Shibaura 4-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8071. This column appears next on Sept. 20.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.