As the music business struggles to reinvent itself for the digital world, the only topic more controversial than what a recording is worth is who exactly should have the power to set its price.

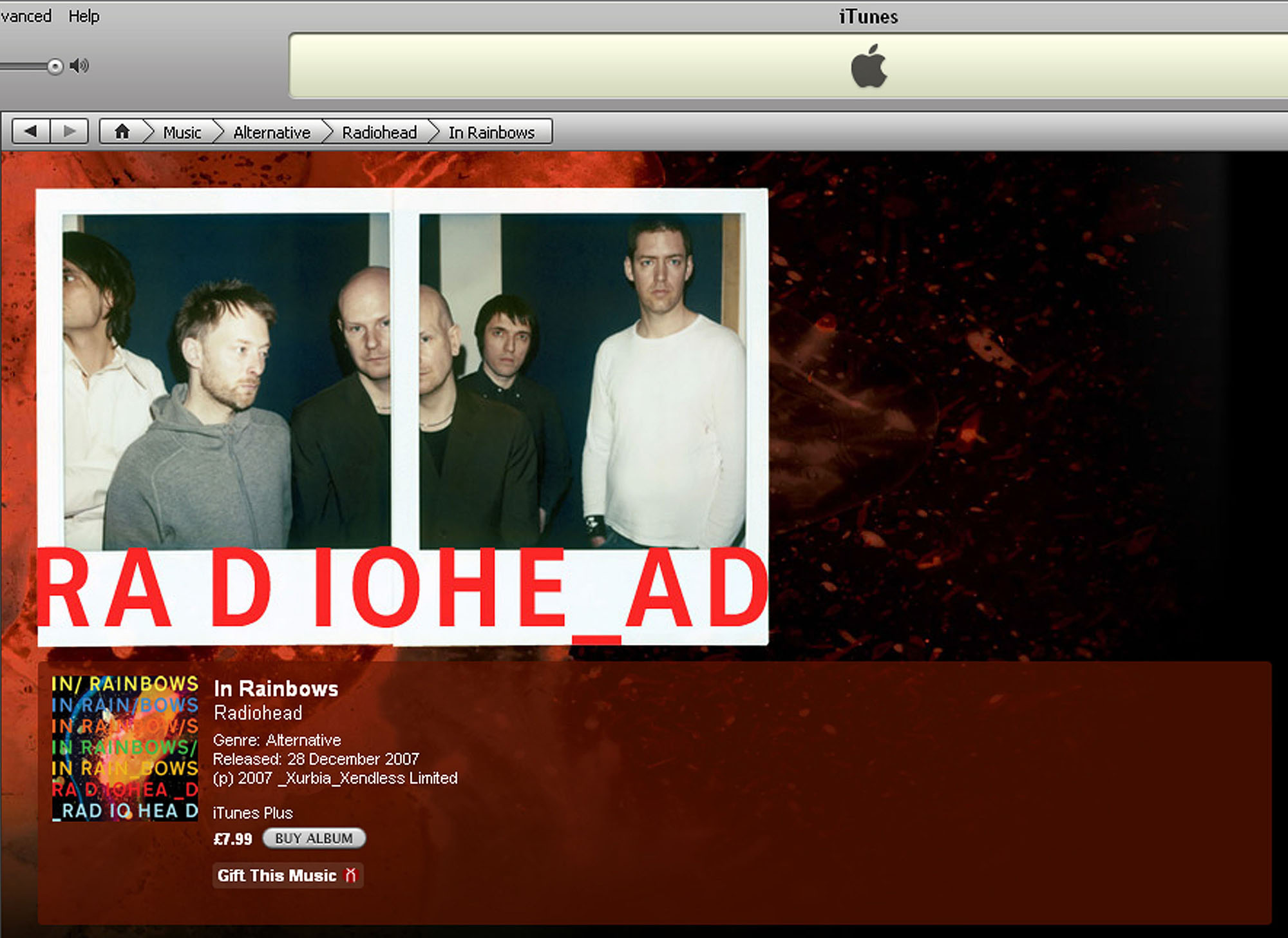

Thom Yorke has weighed in on both questions: first, in 2007, when he made Radiohead's "In Rainbows" album available online on a pay-what-you-want basis, and then last week when he pulled the music of his "other" group Atoms for Peace from Spotify, on the grounds that the online music service doesn't pay new artists enough. So far, however, no one, least of all Yorke himself, seems entirely satisfied with the answers, answers that have import beyond music, across the cultural industries.

Like several other music startups, Spotify offers an "all-you-can-eat" streaming service, as well as a limited free streaming intended to attract new customers. Over the long term, the idea is that the fees from such services will generate enough revenue to replace a significant part of the money labels and artists now make on CD and download sales. One might compare the model to cable or satellite television, where people pay a monthly fee to one company, which then takes the responsibility for paying copyright holders in turn. It's an elegant model: convenient for consumers, profitable for technology companies, and — theoretically, at least — fair to creators.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.