On the second floor of an unassuming building in Tokyo's Shinjuku Ward, three young artisans sit cross-legged on tatami, working. They scrub cherry wood with hog hair before inspecting, scrubbing again, then painting and pressing. It’s near silent but for the gentle bristle and crackle of brush, wood and paper.

We are in the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints, an institution specializing in the traditional production of ukiyo-e. Propped up on zabuton pillows and hunched over modest wooden workstations, the artisans — who all happen to women in their 20s this day — are practicing an age-old craft using the exact same method as when the art form was first popularised over 350 years ago.

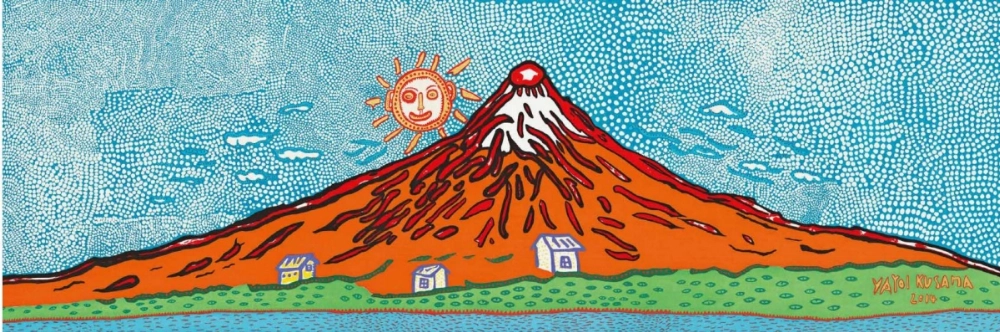

But it’s not just reproductions of Hokusai’s “Great Wave” or Edo landscapes that these artisans are diligently crafting. Since the early 1970s, the Adachi Institute has been working on creating brand new ukiyo-e prints in collaboration with contemporary artists. Now, they are exhibiting the resulting 162 prints by 85 artists in “Ukiyo-e in Play,” an exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum that runs through June 15.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.