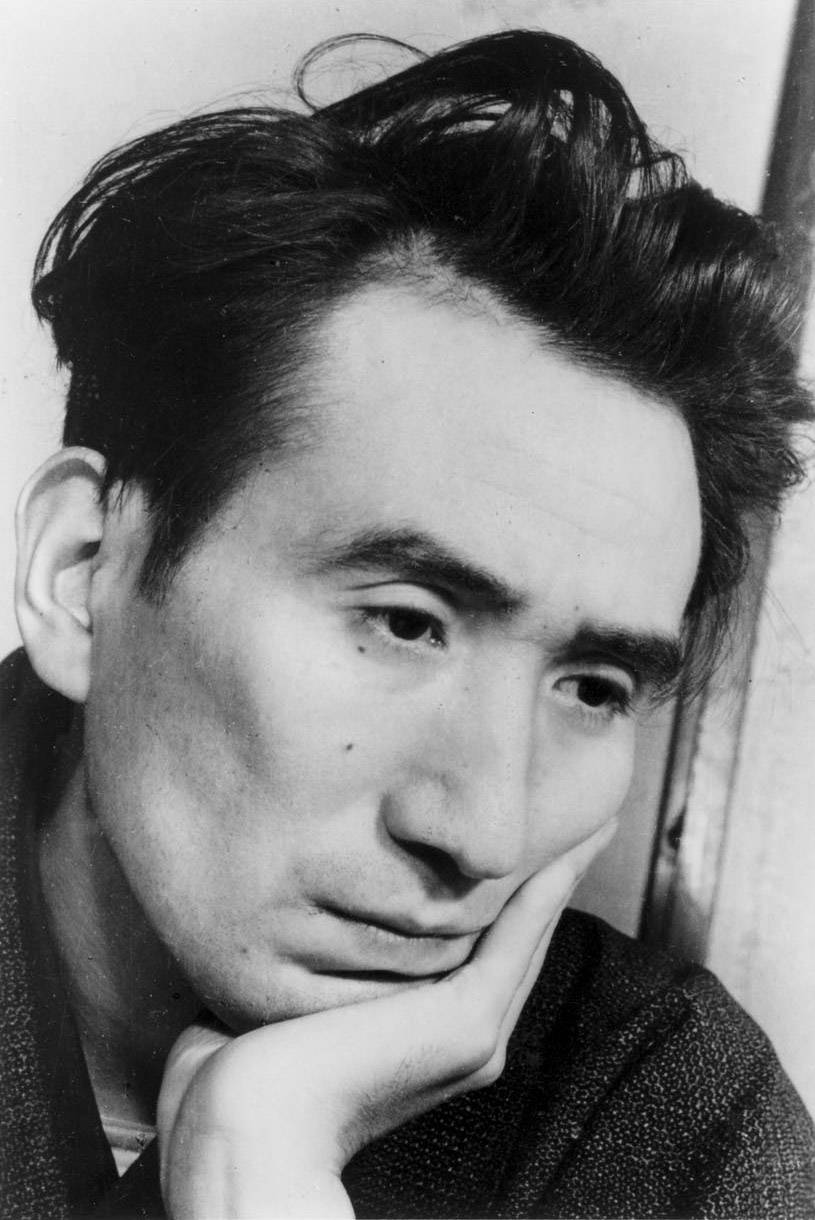

For the first time in English, readers will be able to experience the early days of Japanese fiction’s beloved bad boy.

Osamu Dazai’s 1935 novella “The Flowers of Buffoonery” shares a protagonist, the young, wannabe writer Yozo Oba, with the author’s modern classic novel “No Longer Human,” released more than 10 years later. Yet this is hardly an origin story of Dazai’s troubled narrator. While both books closely mirror the tragedies in the author’s life, the early novella strikes a lighter tone.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.