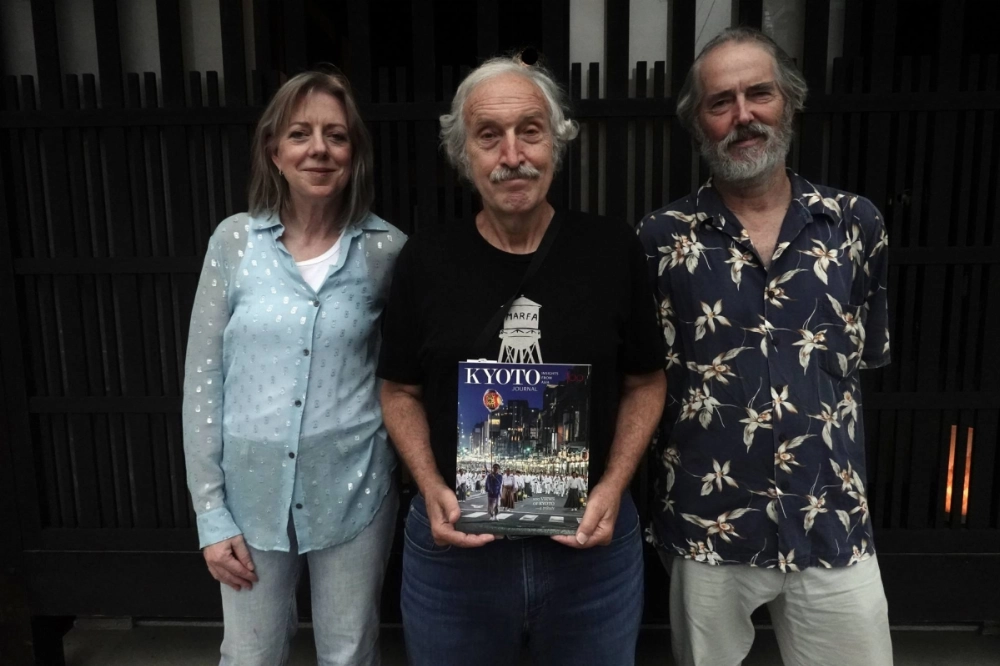

Ken Rodgers, longtime managing editor of Kyoto Journal, passed away on Nov. 4. He was 72 years old.

Rodgers was one of the Kyoto foreign community’s leading lights, respected for his kindness, patience and a positive outlook that inspired an eclectic range of writers, photographers and artists who contributed to the award-winning, all-volunteer magazine.

Born Kenneth Charles Wade Rodgers on May 18, 1952 on the Australian island of Tasmania, he studied printmaking and did a variety of jobs in his native country, and then South Africa, before coming to Japan. Rodgers arrived in Kyoto in August 1982, originally on a working holiday visa, and made a home and community here over the next four decades.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.