Several months ago I made a bet with a friend about how the Hague Convention on international child abduction will be applied after Japan finishes implementing it through domestic legislation. My bet was this: If a Japanese court ever does order the return of a child wrongfully brought or retained here, the first case will be one in which both parents are non-Japanese. Needless to say, I hope to lose.

Despite the Japanese press trying to reduce the complex problem of international parental child abduction to one of Japanese mothers fleeing from abusive foreign husbands, the nationality of the parents involved in child abduction cases should not be an issue under the convention. The treaty is about the best interests of children and is rooted in a couple of fairly simple notions: that what is best for children should be decided in their country of habitual residence, and that this residence should not be subject to change by the unilateral — possibly illegal — actions of just one parent. This is not just a matter of abstract fairness either, since most of the evidence a court might find relevant to deciding what is best for a child after parental separation is likely to be where the child has been living, whether it is school or medical records or the testimony of relatives, teachers, counselors or other people who know the child and their family.

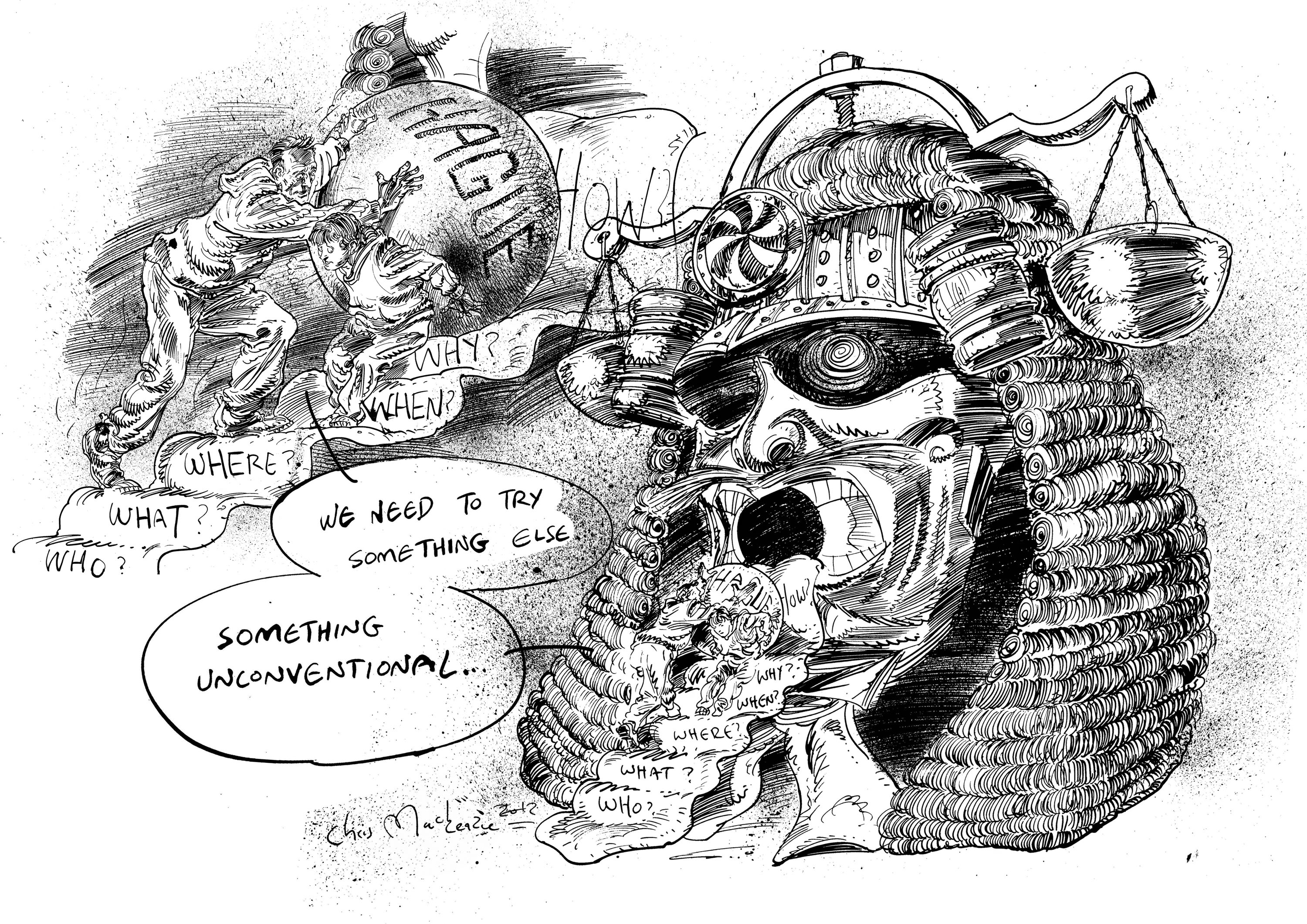

In Japan, however, the "best interests" that tend to get primacy are those of the people who make and apply the law rather than of children. This is why it has always been difficult for me to imagine that Japan joining the Hague Convention will actually result in children being taken away from Japanese mothers and returned to foreign countries (even though all this might mean in many cases is that the taking mother has to apply to a foreign court to relocate to Japan with the children).

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.