Implementing change is often a painful procedure.

That is apparently the case for the leaders working to revamp the landscape of college sports in Japan.

It has been a couple of years since discussions aimed at forming a Japanese organization similar to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, which oversees college athletics in the U.S., and establishing athletic departments at universities began.

These reform measures are intended to give more legitimacy and governance to college sports in Japan.

Sports teams at Japanese universities are given access to school facilities and some subsidies, but are not formally recognized as belonging to the school.

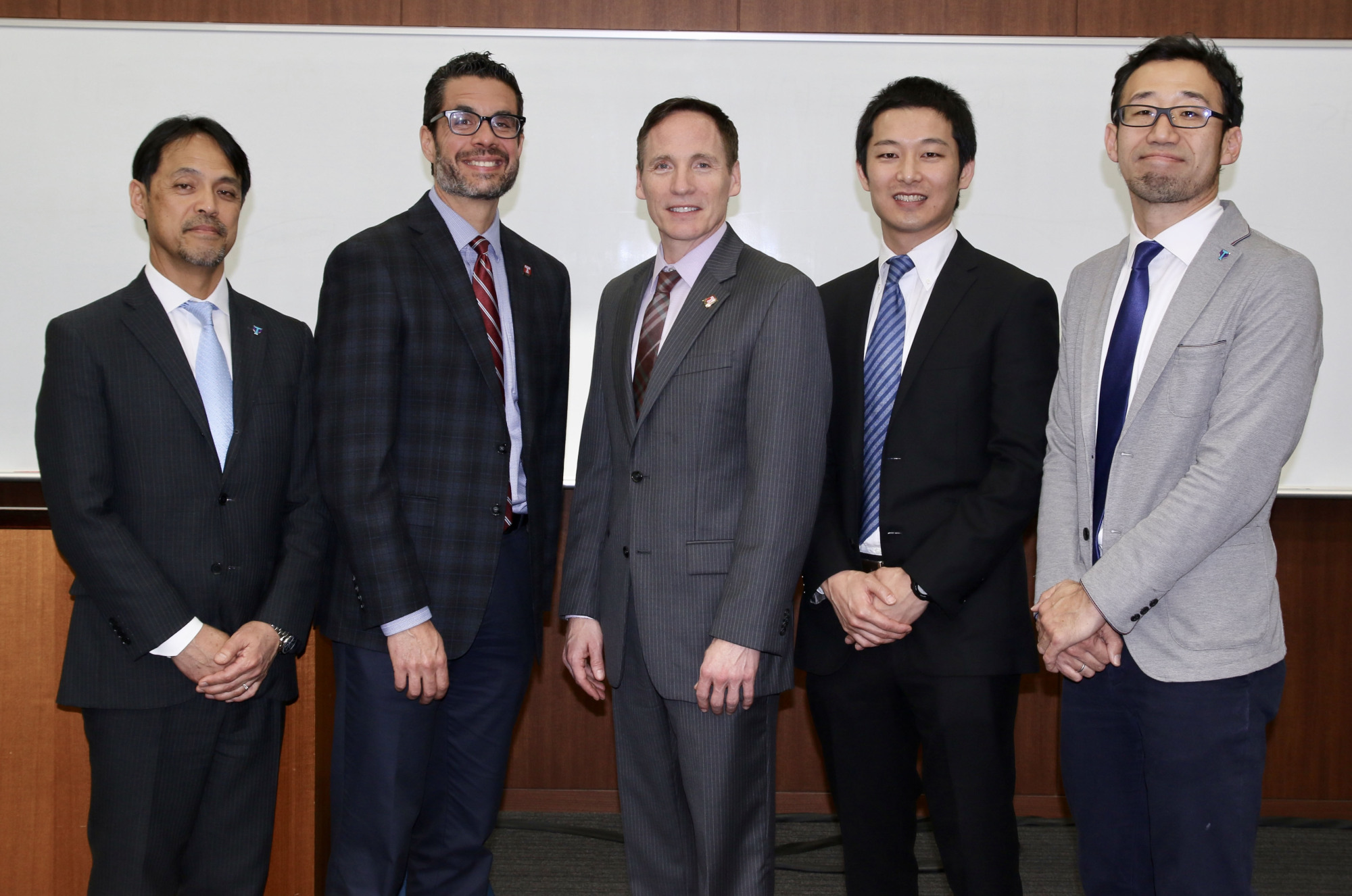

In order to change this, a joint project between the University of Tsukuba, Temple University and Dome Corporation has carried out research on collegiate sports in the United States to examine what would work in Japan.

The project is divided into three phases, with Tsukuba as the test case. The project has recently completed its second phase, which was devoted to preparing an athletic department with a "transitional athletic director" at the Ibaraki Prefecture-based national institute.

Speaking to the audience in a report event at Tsukuba's Tokyo campus on Wednesday, Jeremy Jordan, an associate professor for the School of Sport, Tourism and Hospitality Management at Temple, emphasized — as he has repeatedly done — that the aim of the project is not to copy the U.S. model, but to create one suitable for Japan.

"Hopefully, by sharing information about what's happened over the hundred years in the U.S. in terms of college athletics," said Jordan, an NCAA faculty athletics representative and one of the project leaders. "It helps you build a model that fits here in Japan, maybe skip some of the painful points that we've had in the U.S. in terms of college athletics, and continue to help student-athletes develop both in the classroom and athletically."

Tsukuba was originally scheduled to start up its athletic department in April, after this past year's transitional period.

But Shinzo Yamada, one of the sports administrators at Tsukuba, said his team pushed back the launch to give the transitional team another year of preparation.

Tsukuba has more than 40 sports teams but their reactions to the formation of the athletic department, which is a step into the unknown for them, has been muted.

In fact, only three teams — the baseball team and the men's and women's handball teams — have agreed to act under the umbrella of the athletic department. The men's and women's volleyball teams have agreed to take part as associate members.

But the project team is not disheartened by the blunt response. The members are not naive and knew it would not be easy to change the culture of something that has been in place for decades.

Jordan hinted that things are moving slower than they originally thought. But he added that it's probably "how it should be," to allocate more time to educate those who are associated with college sports in Japan.

"So that people can really be thoughtful about why they want it to happen, why this change should happen," Jordan said.

Daniel Funk, a professor in the same department as Jordan at Temple, described the project as "a big ship in the ocean," because once it starts moving, it becomes "very hard to turn."

Still, Funk seemed a little perplexed to see resistance from sporting officials at Japanese universities, because universities have facilities and already let their students play sports, yet have left them as "private organizations" to act outside their institutional systems.

So looking back at the last two years serving as director of the research project, Funk said that the group has tried to come up with "a change management strategy." The idea is to persuade officials of universities and college sports clubs to understand why the moves are necessary and how it benefits them.

"So moving forward, I think that would be a direction to help other universities deal with both the external and internal politics change," he said.

Yuhei Inoue, an assistant professor in sports management at the University of Minnesota who has also been a key member on the research project, insisted that developing relationships is highly important in Japan when you attempt to modify something.

"So whatever model you try to bring over here, how you explain it to people like coaches and school officials is important," Inoue said. "I think that it is really significant to communicate with them well and earn cooperation from them."

The NCAA was founded in the U.S. in 1906 (it was initially called the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States), essentially because there were too many injuries and deaths related to college football.

Funk said he hopes Japan is "not forced to move quickly" because of a crisis. He wants college sports in Japan to promote "well-being" for the students and student-athletes.

Despite meeting more resistance than originally anticipated, Jordan remains optimistic that the project will eventually work due to growing interest from collegiate officials in Japan.

"It seems like for their interests, because every time we come over here, there's more and more schools that are coming to these functions, it seems there's a lot of discussion, the government wants to create this — Japanese version of the NCAA."

The project will next go into the third and final phase, in which Tsukuba will designate its director and vice director of athletics and prepare to actually run its athletics department.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.