With the U.S. midterm elections looming, the Republican and Democratic parties are ramping up their advertising campaigns in key races, bolstering their social media presence, targeting voters in person and enlisting prominent politicians to endorse candidates at rallies nationwide.

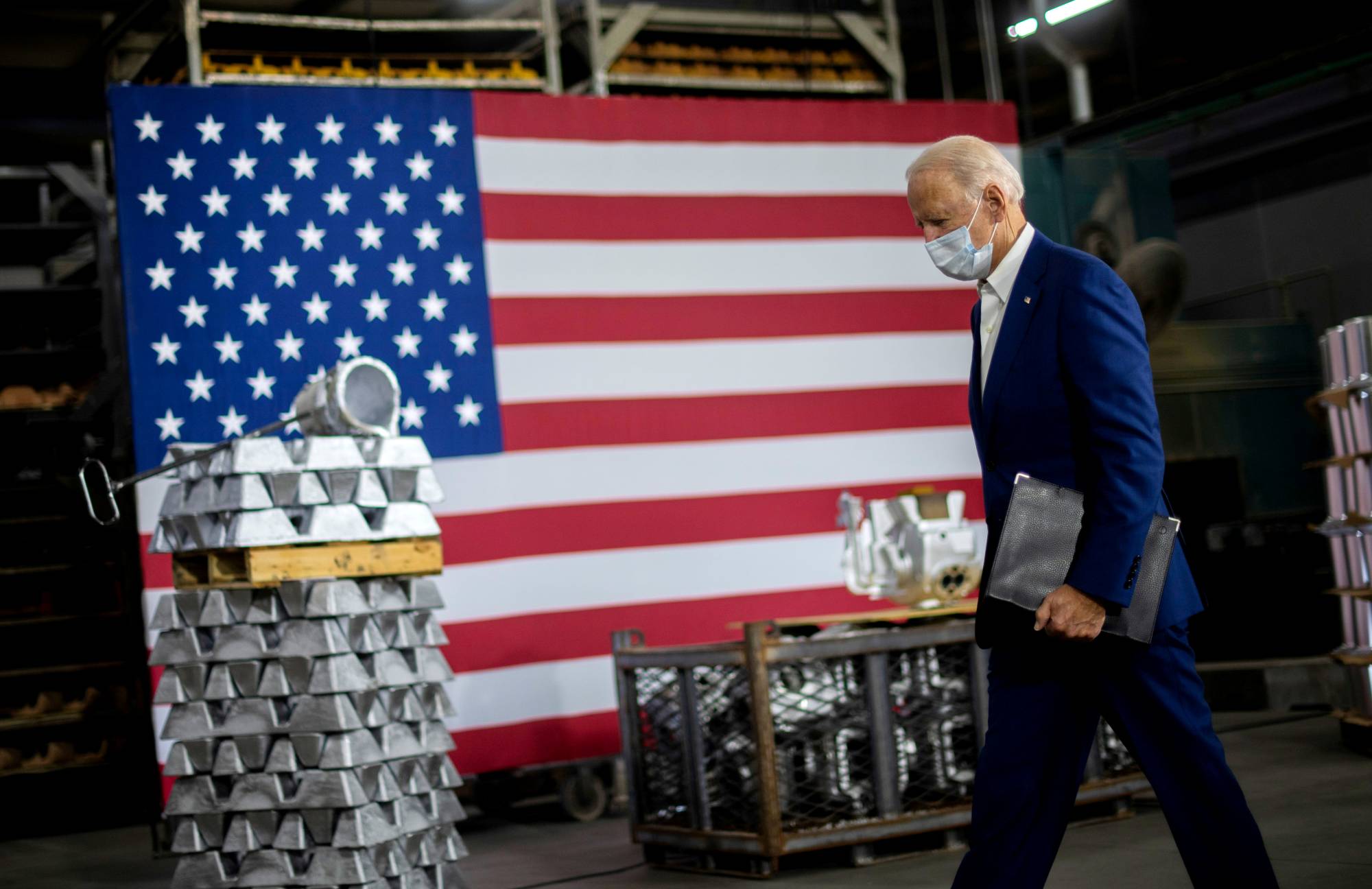

Despite the domestic challenges facing the United States — persistent inflation, declining stock and bond markets, flat job figures and intense polarization — and the resultant low popularity of President Joe Biden, the midterm elections could be much closer than one might expect.

Given the president’s poor support rates, history suggests the Democrats will struggle in the upcoming elections. Democrats hold a slim majority in the House of Representatives, with a number of candidates under threat in competitive districts. A number of veteran Democratic lawmakers have retired from politics over the past two years, which hurts the party’s chances further. And voters generally tend to punish whichever party is in control of Congress irrespective of the country’s actual position.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.