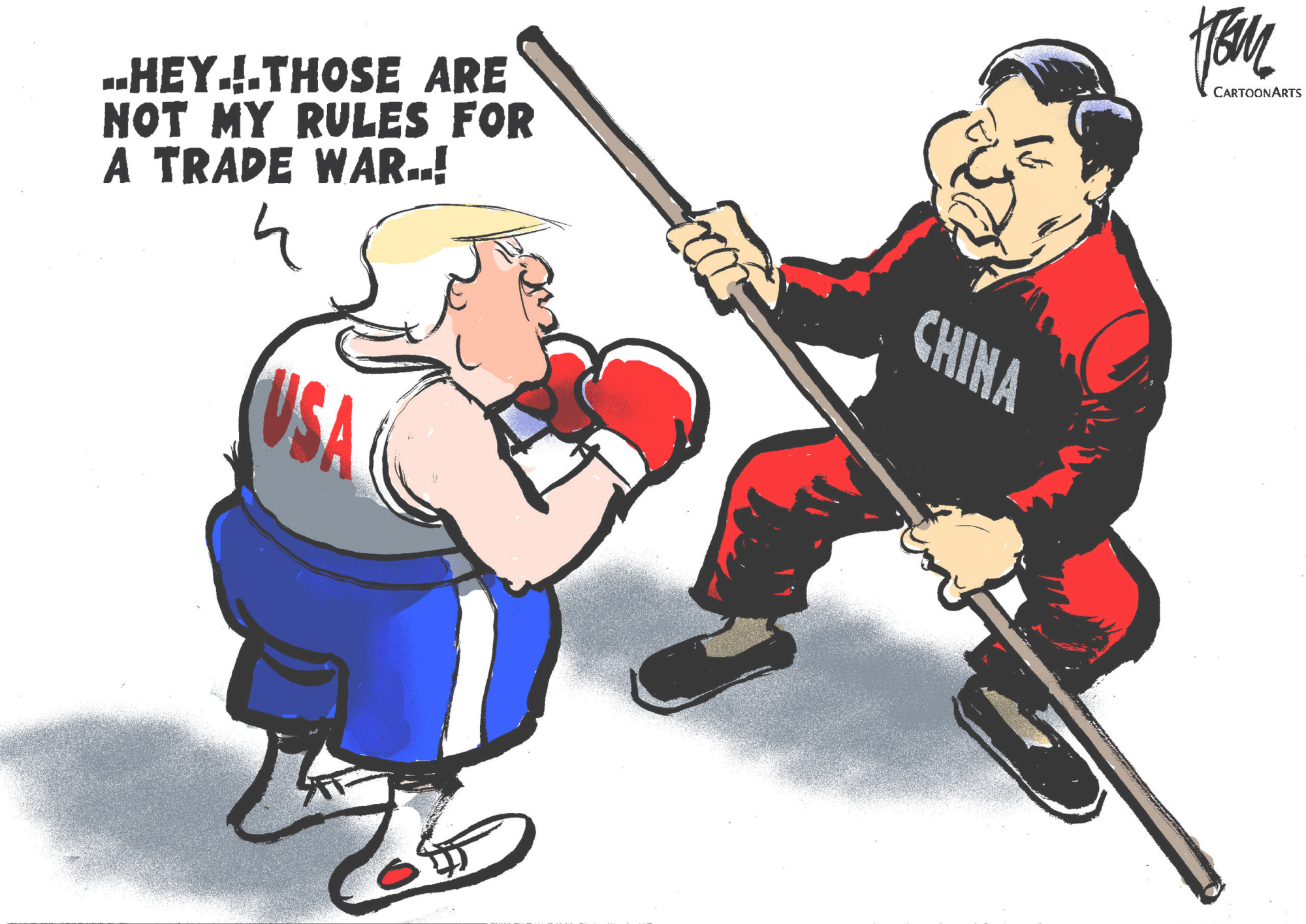

The escalating trade war between the United States and China has sometimes been characterized as what game theorists would call a prisoner's dilemma. A prisoner might benefit by informing on another, but only if the second prisoner does not also betray the first. If both inform, both lose; the best outcome for both occurs if both remain silent. Likewise, an economy can benefit from raising tariffs on another, but only as long as the latter doesn't retaliate; in a tit-for-tat scenario, both lose. In that case, the hope becomes that the losses force the beleaguered parties to recognize their mistake and return to cooperation.

It is a tidy argument. But it does not explain the U.S.-China trade war, for a simple reason: Neither side's motivations are as straightforward as the prisoner's dilemma implies. They much more closely resemble those described by the ancient Greek historian Thucydides in his account of the Peloponnesian War.

To some extent, that 27-year conflict was precipitated by a series of smaller-scale trade and shipping disputes involving lesser city-states. But more fundamentally, Thucydides observed, "it was the rise of Athens," an emerging power, and "the fear that this instilled in Sparta," the leading established power, "that made war inevitable."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.