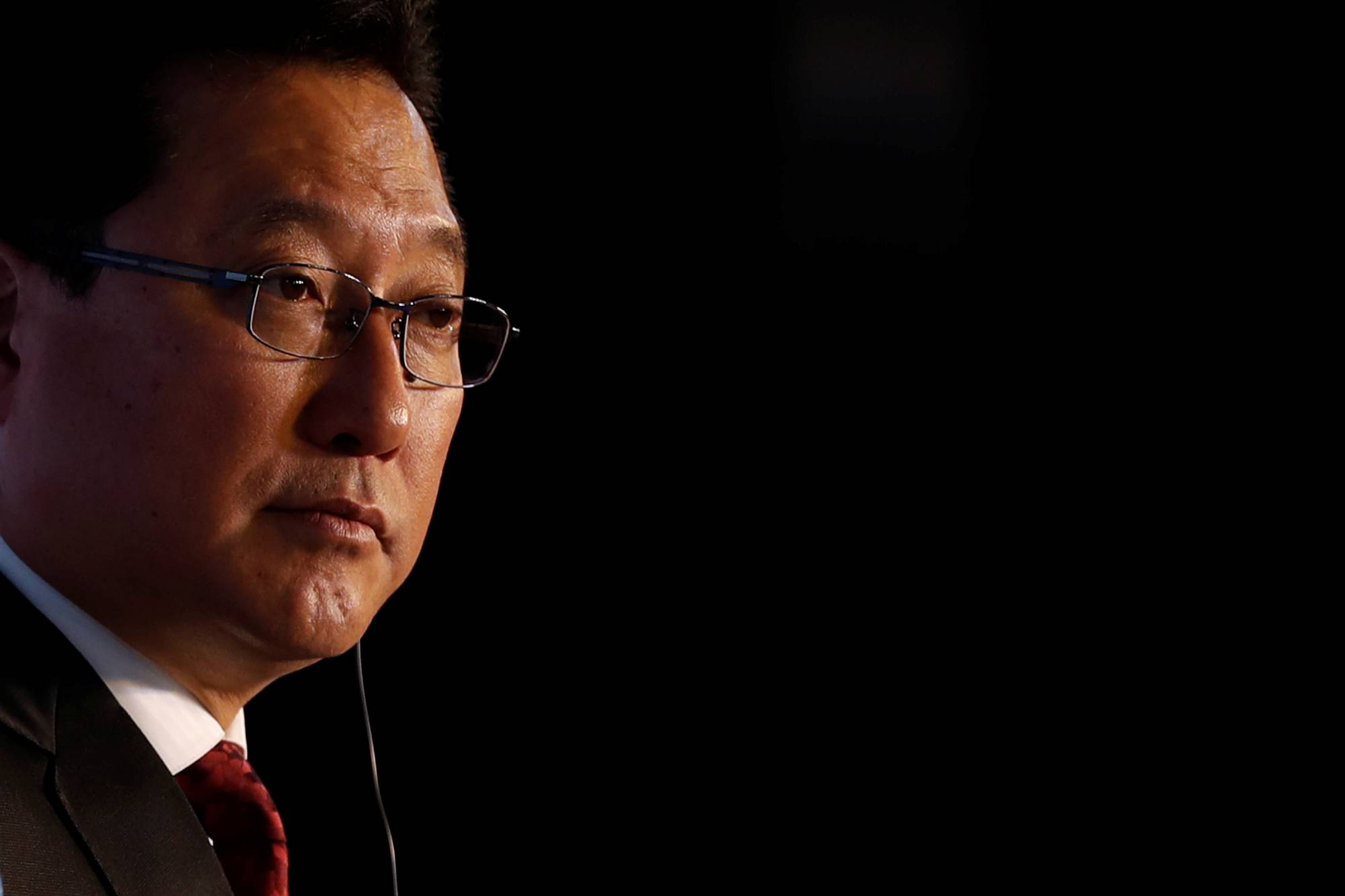

Shigenobu Nagamori, a work-obsessed Japanese billionaire who jokes that he plans to live to 120, had already sidelined three successors when he wooed Jun Seki to join his $37 billion company.

It was November 2019. Nagamori, then 75, invited the younger man to dinner at Ryokuyouso, an exclusive traditional kaiseki restaurant that he owns in Kyoto. There, he made his offer: Seki would join Nidec and become chief operating officer of the world’s biggest manufacturer of electric motors. He would build up its business supplying motors for electric cars, and if that went well, the CEO role would be his.

The timing was no coincidence. A month before, Seki had lost out on the top job at Nissan. The executive, who was 58 at the time, thought the opportunity to run one of Japan’s iconic companies was too good to pass up.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.