Japanese live-action streaming series have struggled to match the global impact of South Korean rivals such as “Squid Game” and “Crash Landing on You.” However, the recent Japan-based shows “Tokyo Vice” and “Shogun” have become popular with international streaming audiences. Both are made by multinational production teams that reject the nearly exclusive domestic focus of the usual drama series backed by consortiums of media companies that have little interest in the overseas market.

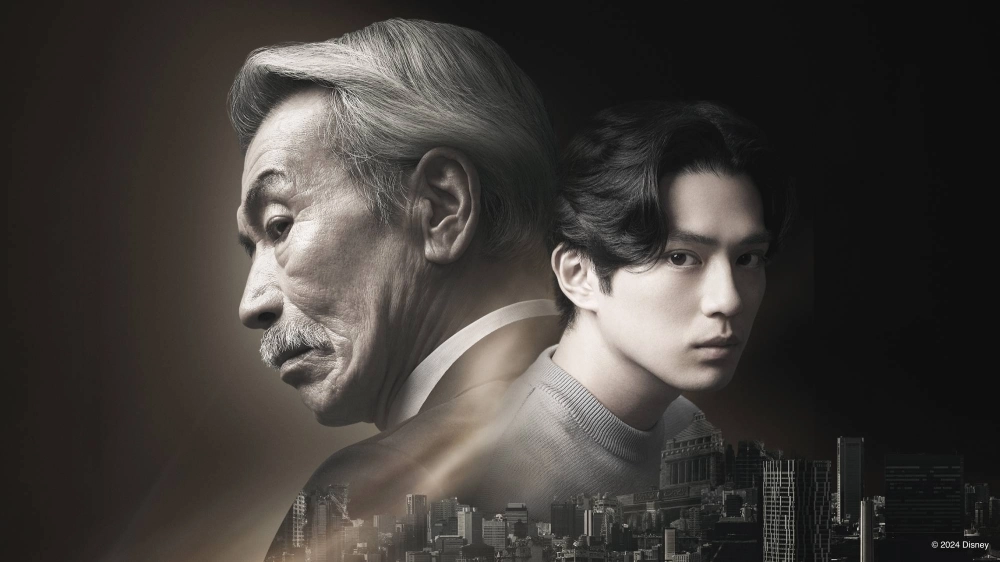

Another Japanese series made with a similar outward-looking approach will drop April 24 on Disney+. Created and scripted by veteran entertainment industry executive David Shin, the 10-episode “House of the Owl” stars Min Tanaka as a powerful political fixer, or “kuromaku,” who has a troubled relationship with his adult children, particularly an idealistic son played by the single-named Mackenyu.

Currently CEO of Singapore-based Iconique Pictures, which produced the series, Seoul-born and U.S.-raised Shin worked in Japan for 10 years as president of the Fox Networks Group. From 2019 to 2023, he was in charge of Disney’s content sales and streaming businesses in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.