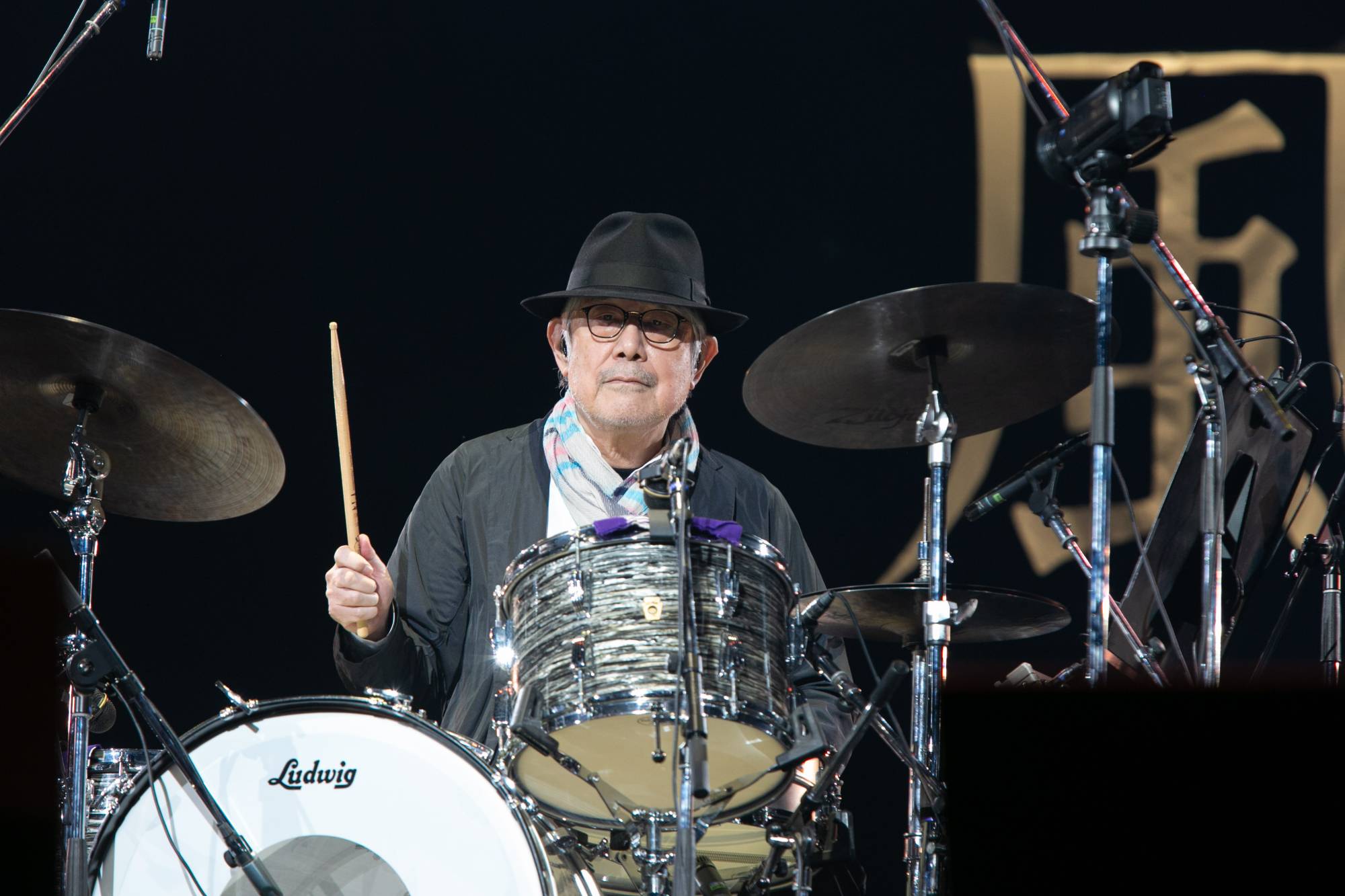

It’s hard to understate the impact Takashi Matsumoto has had on modern Japanese pop and rock music. Known to most for his role in the influential group Happy End, the drummer and lyricist boasts a song catalog that puts him in league with the likes of Quincy Jones and Oscar Hammerstein.

Matsumoto was born in Tokyo’s Minato Ward in 1949, and growing up he’s said to have been a big fan of the Beatles. In college, he began making the rounds of the capital’s then-fledgling live-music community. He joined a psychedelic rock band, Apryl Fool, in the late 1960s, embracing a style that was at the time considered radical compared to the then on-trend “group sounds” artists that mimicked bands like the Beatles.

Apryl Fool released a single album, “The Apryl Fool,” before breaking up. Upon dissolution, however, Matsumoto and bandmate Haruomi Hosono linked up with Eiichi Ohtaki and Shigeru Suzuki to form Happy End. (Hosono would eventually go on to lead Yellow Magic Orchestra, another of Japan’s most-acclaimed acts.)

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.