The word "fukkō" ("reconstruction") — is once again in the air. Ubiquitous during the postwar period, it enjoyed an earlier vogue a generation before as Tokyo was rebuilt after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. But while the word may be the same, its meaning and spirit changes from era to era. A new exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in the Roppongi district of Tokyo gives a visceral sense of just how substantial such generational shifts can be.

The show, titled "Metabolism: The City of the Future", is a trawl through the voluminous archive of the Metabolists, a grouping of young architects and creators who came together in the late 1950s to advance an ambitious program of architecture and urbanism to reshape Japan.

Gathered around the iconic figure of Kenzo Tange, and given coherent voice by the critic Noboru Kawazoe, the group included Masato Otaka, Fumihiko Maki, Kiyonori Kikutake, Arata Isozaki and Kisho Kurokawa — today, a roll-call of the pre-eminent elder statesmen of postwar Japanese architecture; then, a half-dozen vigorous young men in their 20s and 30s guided by a visionary teacher.

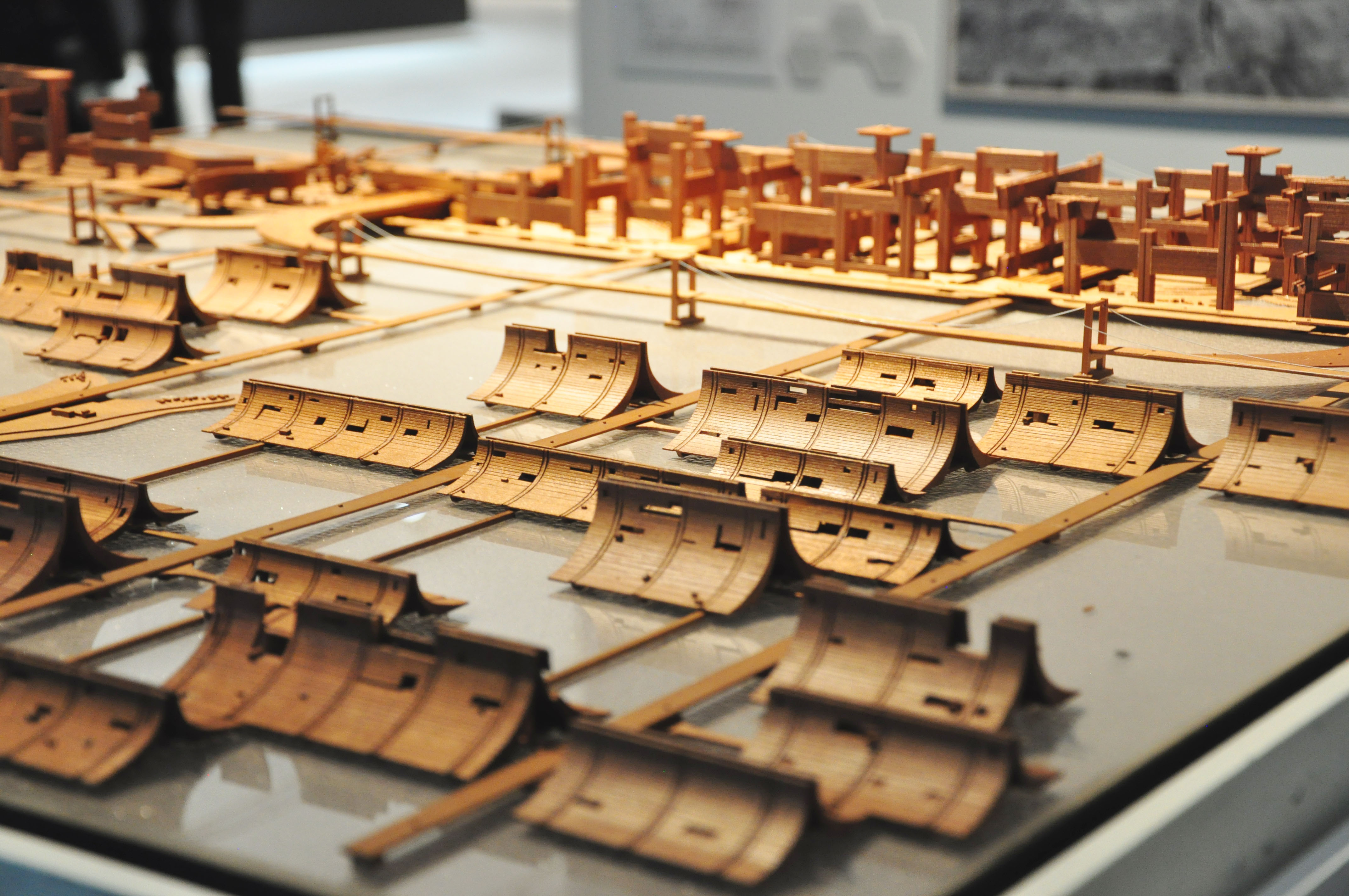

Subtitled "Dreams and Visions of Reconstruction in Postwar and Present-day Japan," the material excavated is quite simply stupendous. Assembling more than 500 items from around 80 projects, the show reveals visions of cities floating on water and spiraling into the air; mechanized pyramids and towers bristling with plug-in capsules for dwelling, linked by huge tubes for services and movement; elevated platforms and artificial ground sheltered by sweeping roofs; grand plans for cities and farms bound into nationwide networks of transportation and communication.

Marshaling models, drawings, photographs, and newly commissioned 3D animations, this is a splendid museum-quality show, both historically significant and immensely timely.

The Metabolists confronted a postwar society undergoing a frenzy of urbanization and industrialization. Both cities and countryside were subject to dramatic change, exacerbating a sense of rootlessness and disorder. A central concern was to find ways of harnessing and coordinating these forces of change within the organizational structure of cities and buildings. This led to proposals that combined durable "megastructures" accommodating movement and services with flexible and replaceable "capsules," which housed the activities of living, working and playing, and which could be easily changed as human needs evolved. Another postwar challenge addressed in Metabolist schemes was the severe limit to the quantity of habitable space for a burgeoning population. The response was to colonize the sea and the air with artificial "land" — as seen in projects such as Kikutake's "Marine City" and Isozaki's "City in the Air."

Such proposals constituted far more than a collection of smart ideas of how to build buildings and cities more densely, flexibly, and efficiently. They amounted to a vast and intricate vision of nation-building, for a country reborn from the ashes of war and the loss of empire. The Metabolist vision was ascendant during the decade of the 1960s, bookended by the World Design Conference held in Tokyo in 1960, which publicly launched the movement, and the Osaka World Expo of 1970, which marked its apogee. It coincided directly with the "Income Doubling Plan" that the Hayato Ikeda cabinet implemented in 1960. This moment constituted, in the words of Rem Koolhaas — perhaps the most influential architect alive and an avid student of the Metabolists' ideas — "a rare moment where government, bureaucrats and artistic architectural circles were connected in a single enterprise."

The nation-building vision was advanced not only through concrete proposals for technologies and systems, but also at the level of meaning and myth. At the heart of the Metabolists' aspirations was the attempt to create a vision of modernity from Japanese rather than Western materials. Sources native to Japan or drawn from oriental traditions were mined to inspire and bolster Metabolist visions, often contrasted baldly against a notionally unitary West.

The emphasis on flux and change was held to be a manifestation of the Buddhist acceptance of impermanence and the Japanese celebration of transience, the result of centuries of building in wood in a land prone to disaster. Traditional architectural forms drawn from timber frames and temple roofs were reinterpreted on massive scales in concrete and steel, as demonstrated in Tange's unbuilt Plan for Tokyo of 1960 and the celebrated Yoyogi National Gymnasium. While we may smile today at such rationalizations, they demonstrate that the Metabolists wielded an art of rhetoric equal to their prodigious architectural artistry -all in the service of their overarching vision.

In addition to the edifying sight of the surviving members of the Metabolists surveying their youthful projects with quiet pleasure, Rem Koolhaas' hawklike aura was unmistakable during the events surrounding the opening of the Mori Exhibition. His presence in the wings of the show signifies a remarkable moment of alignment between architectural discourse in the West and that of Japan. Koolhaas and his office, OMA/AMO, have been pursuing their own detailed study of the Metabolists since 2006, a fact that Mori Arts Museum (MAM) Director Fumio Nanjo and his staff only became aware of last year.

Coordinating their schedules around the International Union of Architects' (UIA) triennial Congress presently meeting in Tokyo, Koolhaas was able to launch the publication of his own voluminous study, "Project Japan," from the same halls that hatched the Metabolists' visions, and in their very presence. The significance of these alignments has been given further uncanny timeliness by the disaster of March 11 and the reconstruction it has now necessitated.

However, despite the ambition of these respective archival reconstructions, a glance at the insipid language and perfunctory themes emanating from the UIA Congress underscores the dispiriting realization of how much the aura and promise evoked by the word "reconstruction" has evaporated in the Japan of today. The future is no longer what it once was — to find it now, we must look to the past.

Julian Worrall is assistant professor of architecture and urban studies at the Institute for Advanced Study at Waseda University. "Metabolism: The City of the Future" at the Mori Art Museum runs till Jan. 15, 2012; admission ¥1,500; open daily 10 a.m.-10 p.m. (Tue. till 5 p.m.). For more information, visit www.mori.art.museum.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.