The hum inside the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium is set to be unlike that of any other sporting event this afternoon. Thousands of fans will wave hands and signs as athletes from around the world take their seats for the opening ceremony of the Deaflympics.

For nearly two weeks starting Nov. 15, about 3,000 Deaf and hard-of-hearing athletes from more than 70 countries and regions will compete in Tokyo, as well as some venues in Fukushima and Shizuoka prefectures. They’ll be joined by coaches, officials and tens of thousands of spectators, with millions more expected to tune in online to watch basketball, swimming, golf, Greco-Roman wrestling and other events.

It is the first time Tokyo has hosted the games, which this year mark both the 25th edition of the Summer Deaflympics and the event’s 100th anniversary — making it the second-oldest multisport festival in the world. The organizing committee hope the milestone will push Deaf sports further into the global spotlight, and that the city, still carrying lessons from the 2021 Paralympics, will continue to evolve into a more inclusive metropolis.

“(We want) to develop the city into a world-class sports hub where everyone enjoys sports,” a spokesperson for the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) tells The Japan Times, adding the games will provide “a valuable opportunity to promote inclusive sports and foster greater understanding of diversity in our society.”

Miyu Nakamura, founder of Japan Sign Travel, which provides tours for deaf and hard-of-hearing people from Japan and overseas, agrees on the potential, noting that the games could spur the country toward becoming a “Deaf-friendly travel destination.”

The question, as the opening ceremony begins and flags rise in silence, is what kind of change the 2025 Deaflympics might spark — not just for related industries, like sport or travel, but for Japan as a whole.

Century of evolution

A century ago, long before even the Paralympics existed, a group of athletes gathered in Paris for the International Silent Games, the forerunner to today’s Deaflympics. The city had hosted the Olympics months earlier, which may have been the reason the New York Times referred to the competition as the “Silent Olympics” in its coverage.

The concept was proposed by Eugene Rubens-Alcais, president of the French Deaf Sports Association, who saw it as a vehicle to provide a dedicated international platform for Deaf athletes to compete at the highest level, to establish an international governing body for Deaf sports and challenge misconceptions about the capability of deaf people.

The event drew more than 120 male and female competitors from nine European nations. Instead of the sound of a starter’s gun, they sprinted and leapt to the flash of lights, astonishing spectators with their skill and precision. By the end of that week, they had not only competed but created a movement: The International Committee of Silent Sports (CISS), the precursor to the International Committee of Sports for the Deaf (ICSD), was established Aug. 24, 1924.

“The competition at the games immediately became the social context for countries to deliberate about similarities and differences in the welfare of their deaf people,” notes the ICSD on its website, adding that “the break-down speed of the prejudice [against deaf people] has increased as more nations and individuals join in the Deaflympic movement.”

Over the next hundred years, the games evolved with the changing world. They became a quadrennial event, a winter edition was added in 1949 (though women weren’t allowed to compete until 1955) and the name gradually shifted from the World Games for the Deaf to, finally, the Deaflympics in 2001.

Today, the ICSD counts 117 member countries, and the games remain distinct from those governed by the International Olympic Committee: They are still organized and run by members of the community they serve. In fact, Deaf athletes cannot compete at the Paralympics unless they have a separate eligible Paralympic disability.

“Deaf people do not consider themselves disabled, particularly in physical ability,” wrote Jerald M. Jordan, CISS president from 1971 to 1995. “Rather, we consider ourselves to be part of a cultural and linguistic minority.”

Despite any institutional changes that came with growth, the mission has remained remarkably consistent. The Deaflympics exist to nurture sporting talent at every level — from grassroots to elite — while fostering well-being, unity and pride within the Deaf community. More broadly, they stand as a reminder of what inclusive sport can achieve: the dismantling of barriers, one game at a time.

Strong track record

Previous host cities have shown the Deaflympics can do more than draw athletes and spectators — they can reshape the cities that hold them.

In 2017, the Turkish city of Samsun used the games as a way to roll out accessibility improvements. The event prompted new and upgraded facilities and the installation of visual signage across public transport networks, making everyday life easier for Deaf residents long after the closing ceremony.

Melbourne, which hosted in 2005, saw a different kind of legacy. The games there generated an estimated $19 million for the local economy and more than 5 million visits to the Deaflympics website, according to then-ICSD President Donalda Ammons — evidence the movement was growing both in visibility and influence.

Taipei followed suit in 2009, using the games to start a public conversation about the needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing citizens. Organizing committee CEO Emile Sheng noted at the time the event achieved its main purpose “to support the hearing impaired.”

Japan knows the power of such legacies. The 2021 Paralympics helped increase public awareness of disability and accelerated the nation’s push toward more barrier-free infrastructure. Four years later, that momentum is being carried forward by the Deaflympics — and now, into law.

In June, Japan enacted the Act on Promotion of Measures Concerning Sign Language, hailed by advocates as a victory two decades in the making. The legislation requires national and local governments to promote the use of sign language — an acknowledgment, finally, that it is a vital part of Japan’s cultural and linguistic landscape.

Now called “shuwa” in Japanese, sign language was once known as “te-mane,” a phrase considered derogatory as it denoted an awkward imitation of spoken languages.

“(Sign language in Japan was) looked down upon as an inferior form of communication,” explains Daigo Ishibashi, president of the Japanese Federation of the Deaf. “Our ancestors could not use sign language publicly. They would sign secretly, only in private. Deaf schools, which they attended, forbade students from using signs.”

Although Japan revised its Basic Act for Persons with Disabilities in 2011 to legally recognize sign language, that came years after the United Nations formally designated it as a language in the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. By comparison, Sweden did so in 1981.

That’s why Japan’s new legislation is “significant,” adds Ishibashi, noting that it codifies five fundamental rights: “to acquire sign language, learn in sign language, learn about sign language, use sign language and protect sign language.”

For Japan’s Deaf community, which officially numbers around 300,000 with potentially millions more affected with some form of hearing loss, this is more than policy — it’s recognition long overdue.

Planned initiatives

Given the new law, strengthening access to information and communication — including through understanding, popularizing and disseminating sign language — is a core element of the Deaflympics Foundation Plan, which has been formulated by the JFD, the Tokyo government and the Tokyo Sport Benefits Corporation.

Ahead of the games, efforts were stepped up to increase both the number of Japanese sign language interpreters — which totaled 4,198 as of October 2024, according to the Japan Information and Culture Center for the Deaf — and the number of users of international sign language, a lingua franca. More than 200 interpreters (half of whom are deaf users of international sign language and half of whom are hearing users of Japanese sign language) participated in JFD-led workshops designed to promote understanding and collaboration during co-interpretation.

Extensive sign language training has been carried out for volunteers and TMG employees who will be involved directly with Deaflympics operations and hospitality. In addition, subsidies have been provided for people to attend training courses in international sign language in the hope of better facilitating communication with attendees from overseas.

To promote a safer environment for deaf people, alerts using lights have been installed at six metropolitan government facilities, including Komazawa Olympic Park, which will host the athletics, handball and volleyball competitions, as well as in the ceilings of almost 700 toilets and changing rooms across the capital. The visual system will alert users in the event of a disaster.

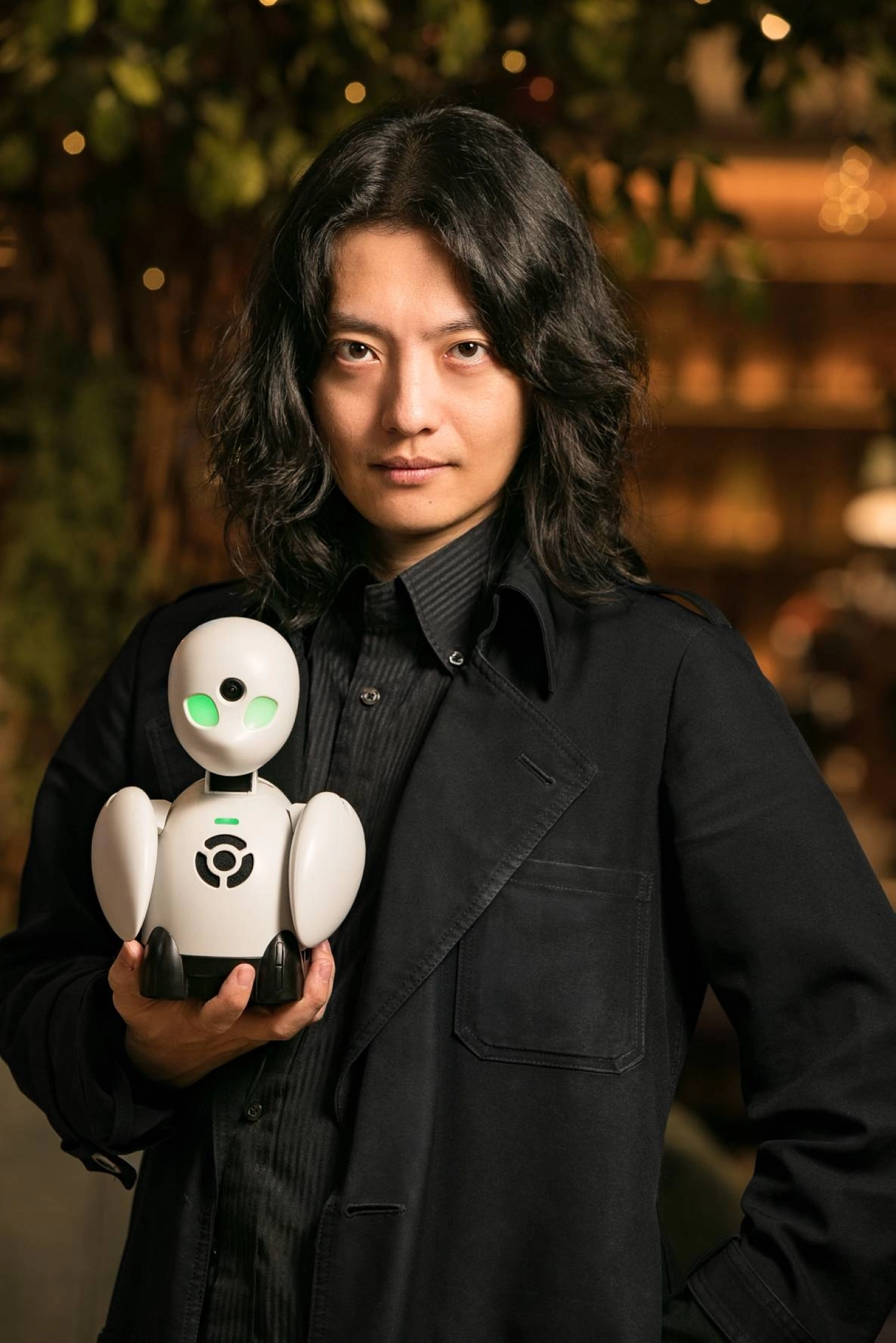

Organizers, meanwhile, are teaming up with technology companies to foster inclusivity. “Universal communication” equipment that displays speech on a glass screen will be deployed at some 40 locations around Tokyo, including sports facilities, and OriHime, a remote-controlled robot, will enable remote attendance of the event. Created by Tokyo-based robotics company OryLab, the machines use real-time, 4K-resolution video and high-quality, low-latency audio, while users on a computer or smartphone can look around in real time.

Engaging with the next generation of adults is another key theme of the Deaflympics Foundation Plan. Children will have the opportunity not only to accompany athletes during ceremonies and assist with medal presentations but also to attend the competitions as spectators and participate in hands-on sports experiences.

“These activities aim to deepen understanding of Deaf sports and foster interest in inclusive sports from an early age,” says the TMG spokesperson. The invitation has also been extended to children from disaster-hit areas of Japan, including Ishikawa, Fukushima, Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, as part of efforts “to combine sports with social support” while “ensuring inclusivity and providing hope.”

Young Deaf athletes with ties to Tokyo are receiving financial support, training assistance and promotional opportunities through the Tokyo-Yukari Junior Para-Athlete Program, an initiative launched to help para-athletes represent Japan in future international competitions such as the Deaflympics and Paralympics.

Ripple effects

Although the greatest impact of the Deaflympics is expected to be in the capital, the venue for 19 of the 21 sports, other parts of Japan are seeing benefits from supporting the games as well.

Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, hosted the 83-member Brazilian delegation’s pre-event training, which involved athletes and coaches preparing for six sports over four days. During the remaining two days, the delegation joined events designed to build anticipation for the games and took part in cultural exchange activities with residents.

Takashi Daito, commission group leader of the city’s sports promotion division, says the initiative fosters greater understanding not only of deaf people but also of people of other nationalities, noting the engagement with Brazilian residents is especially meaningful since Hamamatsu has the largest Brazilian population of any municipality in Japan.

“Through hosting, we hope to contribute to realizing an inclusive society where people with diverse differences respect and support one another,” he says.

Farther south, in Nagoya, officials are watching Deaflympics-related activity as they prepare to host the fifth Asian Para Games in October 2026, another first for Japan. The city held a series of “one-year-to-go events” in September and October.

Organized by the Asian Paralympic Committee, the games are designed to promote the Paralympic movement and expand competitive sports opportunities for people with disabilities across Asia. About 4,000 athletes from 45 countries and regions are expected to compete in 18 sports over seven days.

Like Tokyo with the Deaflympics, Nagoya hopes hosting the games will drive greater inclusivity in the city. But even as major cities leverage these events to improve accessibility and understanding of people with disabilities, efforts have yet to reach the entire country. A nationwide survey conducted in 2023 by the Nippon Foundation Para Sports Support Center found that while 98% of respondents were aware of the Paralympics, only 16% were aware of the Deaflympics.

To build an inclusive environment for all, raising awareness of the needs and abilities of people with disabilities must extend beyond host cities. Whether through local sports, education or community events, the movement toward inclusivity depends on shared effort — one that needs to continue long after the games end.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.