Until recently, Japan's elite para-sport athletes have struggled to earn support from their workplace as they aim to represent their country in international competition.

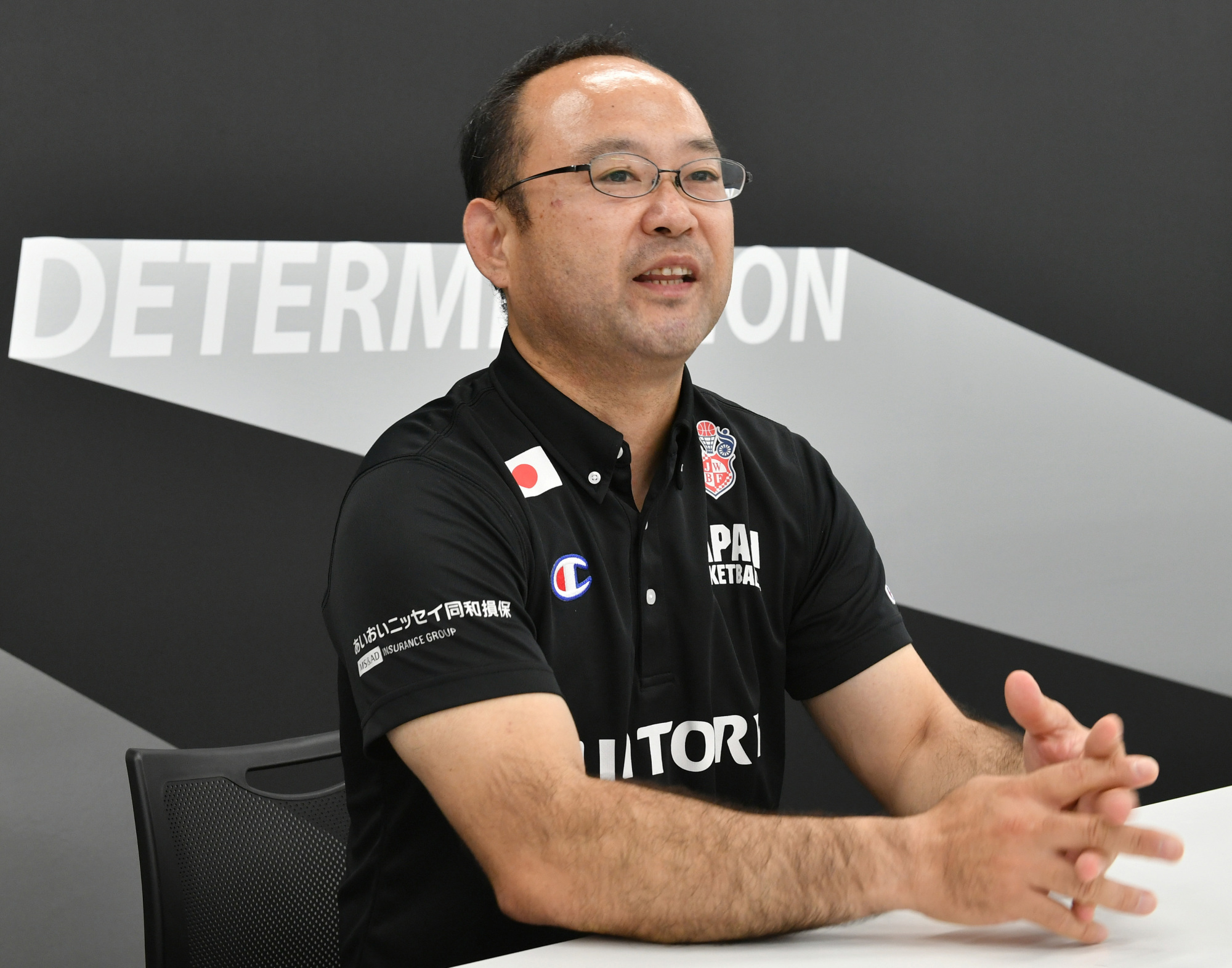

Shinpei Oikawa, the head coach of Japan men's wheelchair basketball national team, vividly recalls a conversation between one of his players and his company boss shortly after Tokyo was awarded the right to host the 2020 Paralympic Games in 2013.

"What is the difference between taking time off to join the national team's training camp and going to Disney Land?" asked the boss, according to Oikawa.

Even national team members have faced opposition from bosses and co-workers, especially when attempting to take time off in order to participate in team activities or competitions.

"Sometimes the athletes had to change their occupations, or faced a tough choice between playing basketball or keeping their jobs," Oikawa said in an interview with The Japan Times at Para Arena in Tokyo's Shinagawa Ward last month. "But that has dramatically changed in the last two years (since the 2016 Rio Paralympic Games). A lot of companies now accept para athletes as employees. Their support and understanding are much better. It is much easier to take days off from work."

He added: "The economic environment has also changed. The budget for training programs increased from ¥5 million to ¥20 million and we have earned more sponsorships. We don't have to pay by ourselves for anything related to national team activities as we needed to in the past."

According to Oikawa, a former basketball player who lost his lower right leg to osteosarcoma when he was 16 years old and turned to wheelchair basketball after a five-year battle with the disease, many athletes used to participate in practices or training camps on their own. This included paying for transportation and accommodations for team activities, which totaled just 40-50 days per year when Oikawa became the national team's head coach in 2010.

"It was also difficult to find training facilities where about 30 people could spend the whole week together," said Oikawa. "There were no such gymnasiums or hotels in Japan. I used to travel all over Japan to find appropriate facilities.

"Gymnasiums often have time reserved for public use, preventing us from booking a full week. Para athletes were not always given priority for reservations, even though we are talking about national team players."

But circumstances have improved considerably, the 47-year-old from Chiba Prefecture insisted. The National Training Center, which was established in 2008 in Tokyo's Kita Ward, provides training facilities. Some gymnasiums and hotels offer opportunities for weeklong training camps.

Improvements in these circumstances allowed Oikawa to increase the team's yearly activity schedule to 100 days following its ninth-place finish at the Rio Paralympics.

"We had increased our practice time, but we were still not good enough to compete against the world," Oikawa stated. "The national team was like an All-Star team selected from domestic clubs. We had good players but we were not good as a team. To be competitive in the world, even 100 days of team activities including competitions is not enough."

For 100 days a year, Oikawa's team now trains at Chiba Port Arena. Upon learning of plans to establish Para Arena's gymnasium, he secured another 50 days of court time, allowing the team to train three days a week.

"To compete in the world, you need a strategy. But the strategy doesn't work properly unless you are physically and technically sound," Oikawa said. "You need practice days and facilities to improve those things.

"Increasing our practice time gives me more ideas and helps me fit those ideas to the players' motion.

"It is amazing how drastically everything has changed after the Rio Games. Just a few years back, it was so hard to earn even ¥300,000 by soliciting many companies for sponsorships," Oikawa said with a laugh. "Now we earn big money for small logos on the uniform. Now we're struggling to catch up to these rapid changes."

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.