A “great day for European solidarity” is how Germany’s finance minister described last week’s $590 billion eurozone virus rescue package, clinched even as Europe’s North and South haggle over the cost of cleaning up the economic wreckage left by COVID-19. The package would allow countries to borrow from the euro region’s rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism, for health-care spending without policy constraints, up to a certain amount.

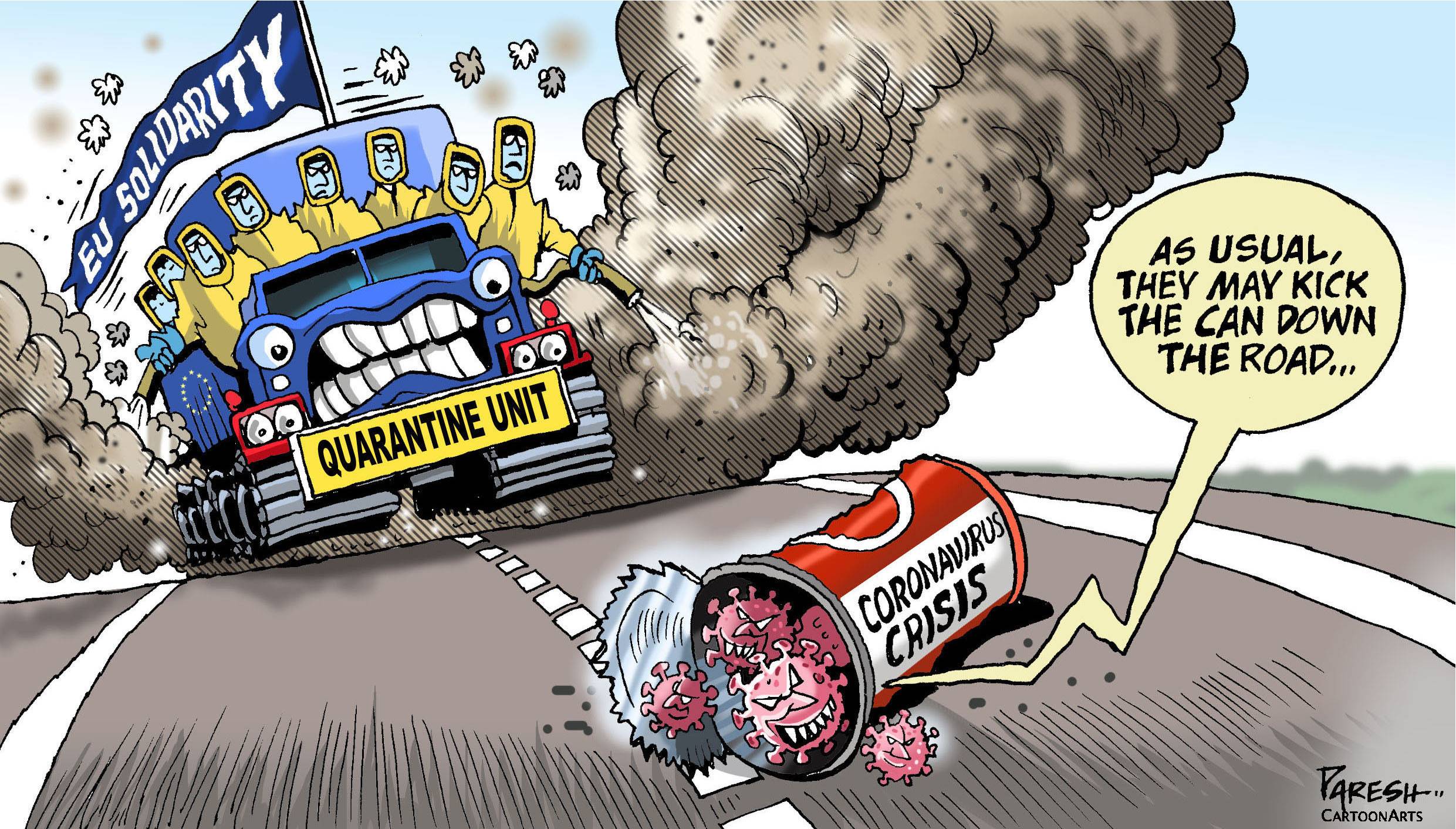

The focus on money is understandable, given the looming recession that’s expected to be deeper than the crisis of 2008. But it obscures a glaring failure of the European Union that may have made both the human and financial cost of the pandemic worse: A lack of coordination and collaboration in health-care policy.

Despite a common market, a (mostly) common external border, and a common health-care challenge in the shape of an aging population, the EU’s 27 member states have scattered like mice when fighting the coronavirus. At the beginning of the crisis, Italy, the first and worst hit in Europe, begged its partners for masks and equipment - not money. The response was a string of border closures and the hoarding of medical supplies for domestic consumption. By the time France, Spain and Germany instituted their own lockdowns, it was clear there would be 27 different responses to the coronavirus, not one “European” one.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.