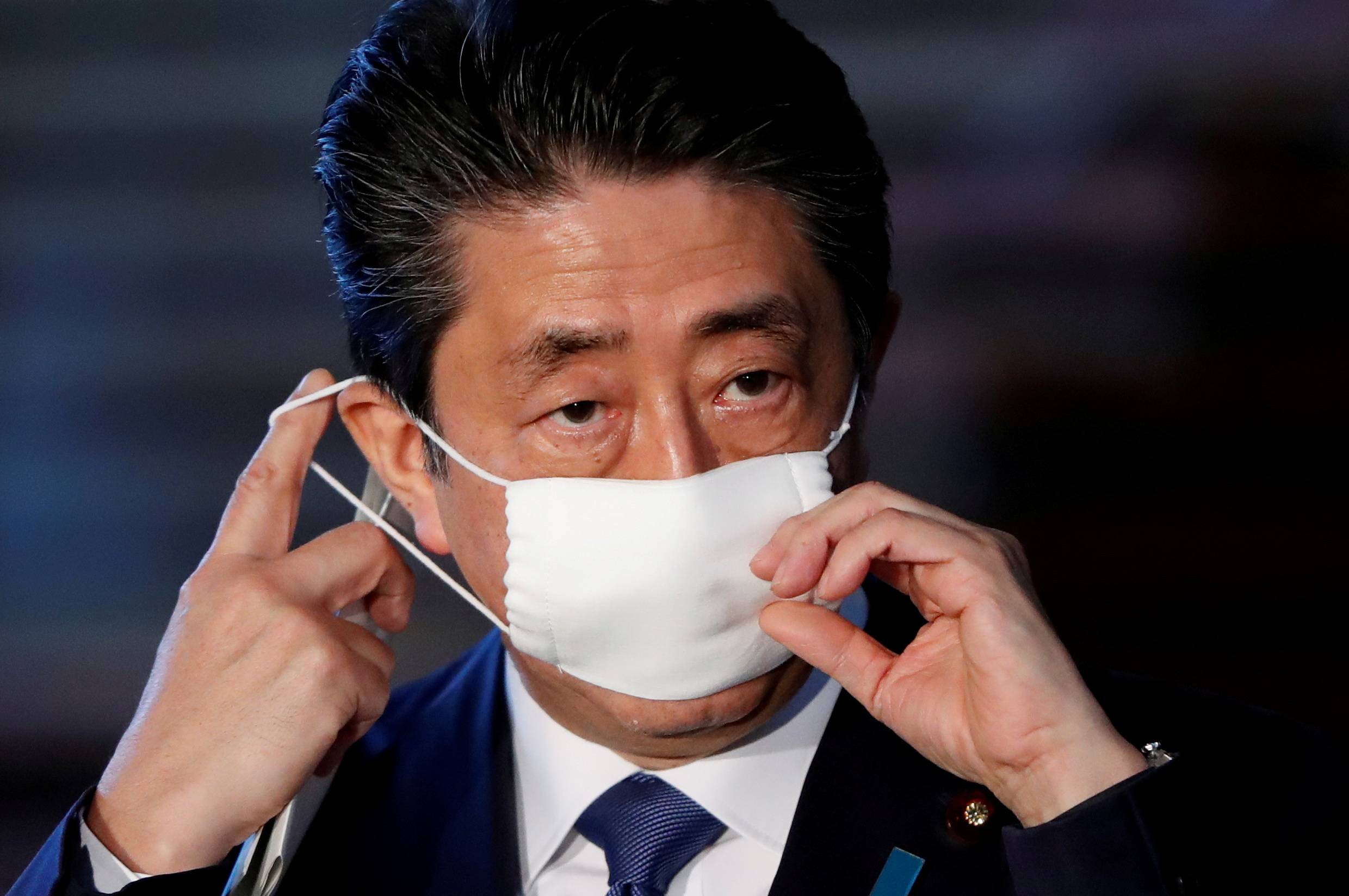

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe last week declared a state of emergency due to the nation’s rising COVID-19 infections. But the measure, made possible by a recent amendment to the law against infectious diseases, only empowered governors of the designated hot-spot prefectures to request citizens and private businesses to practice social distancing, such as minimizing outings, working from home, and closing or reducing hours of the businesses. The lack of enforcement provisions, such as fines, invited broad skepticism as to its effectiveness.

Abe’s “soft approach” in the critical make-or-break stage of the outbreak has been attributed to the limited legal authority of the government and the uncertainties about the epidemic in this country. However, given that even the opposition parties are criticizing Abe of “missing the right timing to declare an emergency by a week” and that his Liberal Democratic Party itself did not call for a stronger amendment to the anti-infectious disease law, Japan’s soft approach must have its origin somewhere else.

Despite Abe’s reputation as a leader capable of making bold decisions, such as altering the government’s interpretation of the Constitution over collective self-defense, his response to the novel coronavirus outbreak that started in Wuhan, China, was slow and incremental from the beginning.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.