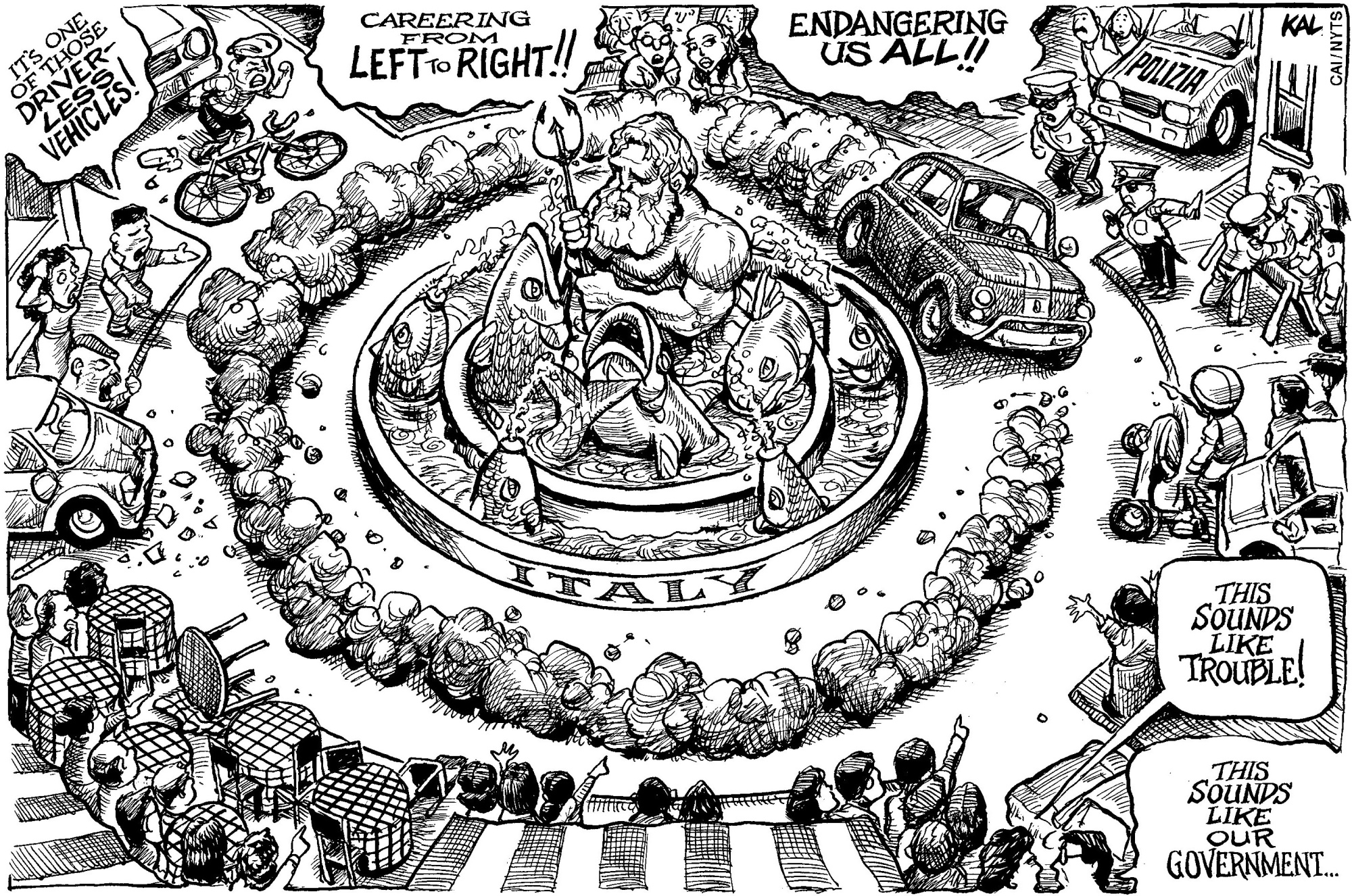

The Italian crisis is over, and has just begun. Its dimensions go far beyond Italy; they are now European, even global. The near three-month long improvisations on a theme of governance ended last Thursday with the announcement of an administration headed by Giuseppe Conte, a law professor with no government experience tasked with running a Cabinet controlled by the leaders of the two parties which form that administration — a signal of weak, divided and warring politics at the summit of power for the foreseeable future.

It also reveals something deeper: the chronic inability of the Italian state to find a political floor solid enough to undertake the changes necessary to put the country — all of it, not just the wealthy north — on the road to modernization.

In Italy's case, that means a version of modernity which provides for its systems — political, economic, industrial, social provision, policing, security — to work with relative efficiency and transparency, untied to organized crime or networks of corruption. The politicians' failure to allow necessary reforms has meant, over the past quarter of a century, the demagogic and aimless premierships of Silvio Berlusconi, the floundering of center-left governments, reformist but continually undercut from within their own ranks, and technocratic governments with no popular base and thus limited leverage.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.