There is a consensus that aggression by one nation against another is a serious matter, but there is no comparable consensus about what constitutes aggression. Waging aggressive war was one charge against Nazi leaders at the 1946 Nuremberg war crimes trials, but 70 years later it is unclear that aggression, properly understood, must involve war, as commonly understood. Or that war, in today's context of novel destructive capabilities, must involve "the use of armed force," which the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court says is constitutive of an "act of aggression."

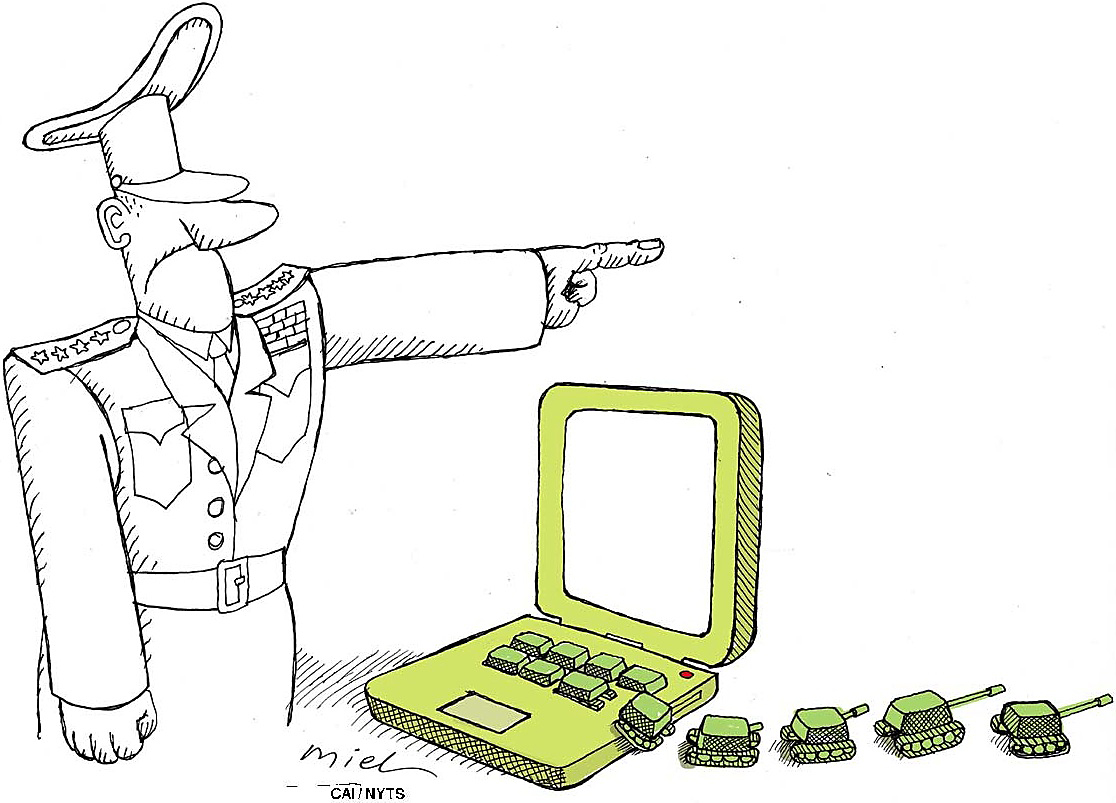

Cyberskills can serve espionage — the surreptitious acquisition of information — which is older than nations and not an act of war. Relatively elementary cyberattacks against an enemy's command-and-control capabilities during war was a facet of U.S. efforts in Operation Desert Storm in 1991, in the Balkans in 1999 and against insurgents — hacking their emails — during the "surge" in Iraq. In 2007, Israel's cyberwarfare unit disrupted Syrian radar as Israeli jets destroyed an unfinished nuclear reactor in Syria. But how should we categorize cyberskills employed not to acquire information, and not to supplement military force, but to damage another nation's physical infrastructure?

In World War II, the United States and its allies sent fleets of bombers over Germany to destroy important elements of its physical infrastructure — steel mills, ball bearing plants, etc. Bombers were, however, unnecessary when the U.S. and Israel wanted to destroy some centrifuges crucial to Iran's nuclear weapons program. They used the Stuxnet computer "worm" to accelerate or slow processes at Iran's Natanz uranium-enrichment facility, damaging or even fragmenting centrifuges necessary for producing weapons-grade material.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.