The week before last scientists announced they'd discovered a gene spreading among bacteria in China that renders them resistant to some of the world's most powerful, "last resort" antibiotics. If such invulnerable bugs spread, doctors may soon lack the tools needed to combat infections, whether contracted through chemotherapy, surgery or even simple cuts. Indeed, the post-antibiotic "apocalypse," as this scenario has been known for a decade, may already be upon us: There's evidence that the resistant genes have made their way to Laos and Malaysia.

Antibiotic resistance isn't new. Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, presciently warned in his 1945 Nobel Prize address that casual overuse of his miracle drug could promote resistance. In recent years, the United States has suffered several cases of foodborne illnesses that didn't respond to existing drugs. But the real threat lies in China, where a large, dense population and close interactions between people and livestock have long made the country a breeding ground for new infectious diseases. To control the problem, the world has to control it in China first.

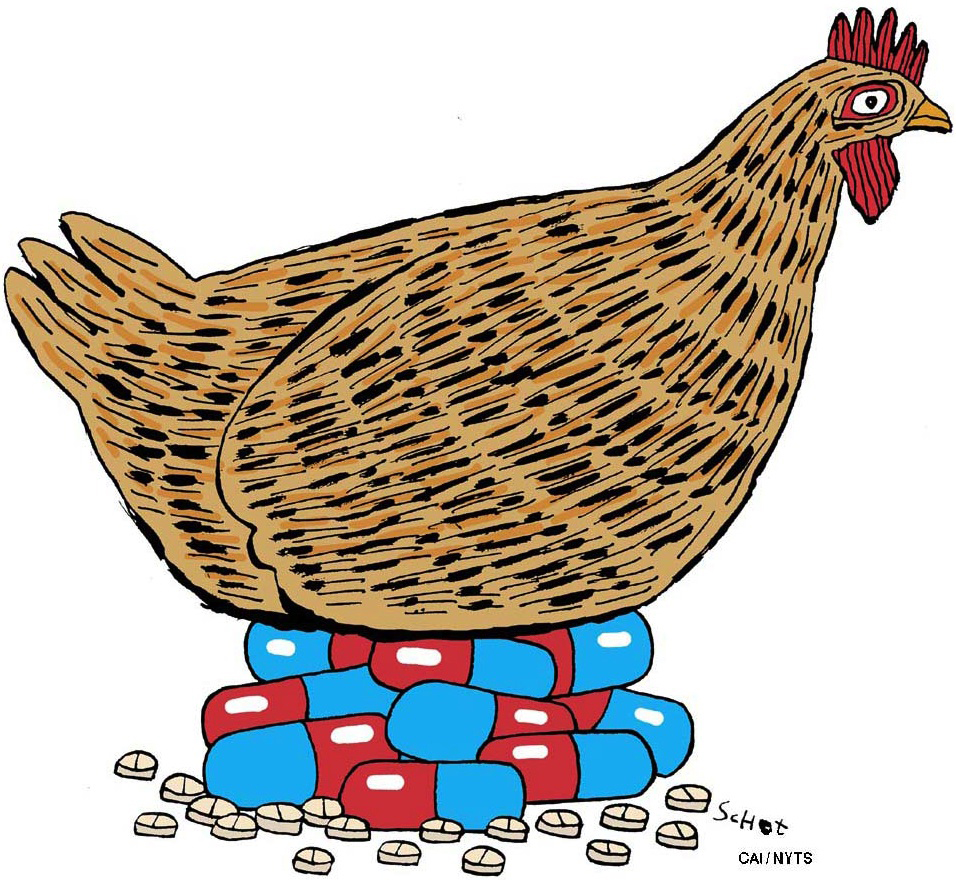

That won't be easy. China's millions of farmers are notorious for pumping their livestock full of antibiotics — roughly three times more, pound for pound, than counterparts in the U.S.; agriculture accounts for perhaps half of antibiotic use in China. The practice, pioneered in the 1940s in the U.S., increases yields for farmers, but also creates an ideal environment for bacteria to develop resistance. Bigger herds offer bigger evolutionary opportunities and China — with the world's largest pig and poultry industries — is particularly susceptible. The drug-resistant gene that scientists recently reported is believed to have evolved in Chinese pigs.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.