In 1993, when large tracts of wilderness on the Kagoshima Prefecture island of Yakushima were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, environmentally minded observers the world over celebrated. But the real battle to save the island's forests had been fought — and won — a decade earlier. One of the men at the center of that fight was Masaharu Hyodo.

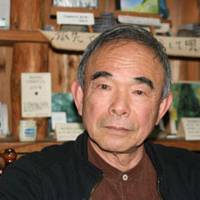

Explaining that struggle to The Japan Times earlier this year, the crystal-eyed Hyodo smiled reguarly as he recalled times past. Born on Yakushima in 1941, he said that in his childhood the whole island was his backyard. "I used to go out and just spend the whole day playing on the beach, in the rivers and mountains," he said.

Lying off the southern coast of Kyushu, Yakushima is a large, essentially circle-shaped island consisting almost entirely of mountains that shoot up from sea level to almost 2,000 meters in height. The combination of warm southern seas and such high peaks gives the island one of the highest average rainfalls in the world — amounting to a staggering 10 meters a year in some areas. That climate, in turn, has produced stands of Yakusugi (cryptomeria) trees that, some say, are now more than 7,000 years old.

Yet, by the time Hyodo was born, the centuries-long process of deforestation on the island had entered what might be called its second phase — the last point at which the forests could conceivably be sustainable.

Logging began on Yakushima early in the Edo Period (1603-1867), when the island's feudal lords in Kyushu asked the locals to produce wooden roof shingles. The islanders reportedly appreciated the work, as there were few other ways to make a living in their mountainous home. Still, it was tough labor — a group of eight men would take up to 10 days to fell a single tree.

The second phase of logging came with the dawn of the modernizing Meiji Era (1868-1912). As the new central government that took over from the feudal Tokugawa Shogunate sought to exert its authority, it nationalized much of the nation's forests, including 80 percent of those on Yakushima. Logging continued in these areas, but its pace was still restricted by the tools available then: axes and saws.

The third stage started around 1960, when the chainsaw arrived. A single logger could now complete in 20 minutes what it used to take eight men 10 days to do. In that year, too, Hyodo graduated from high school — but says he was deaf to the buzz of the industrial revolution occurring in the mountains.

"At the time people would joke that the only product Yakushima had to offer was the labor of its youth," Hyodo recalled with a laugh. "The young locals all left the island to find work."

Hyodo was no exception — he ended up working at the weather station at Haneda in Tokyo. But it wasn't long before he became aware of the devastation being inflicted on his home island.

"I went back to Yakushima every now and again and I started to see big logs piled up at the ports — really big logs — and they were destined to be used for pulp," he said. The other thing that struck him was that even as the logging industry grew, the local population declined.

"It was hard to see that this was benefiting the island," Hyodo said.

Saburo Nagai, another local who has known Hyodo since those days, explained: "There were professional tree-fellers who came to Yakushima from all over the country."

Sensing that the fate of Yakushima had been wrested from the hands of the locals, Hyodo and other Yakushima natives started meeting in Tokyo to discuss how they could try to rectify the situation.

It turned out that the biggest problem came from the people they had left behind on Yakushima. During a 1969 trip there from Tokyo — a journey that took 33 hours by train and then ferry — they tried to make their fellow islanders aware that the forests were quickly vanishing.

"What would you know, you're living in Tokyo," Hyodo recalled being told again and again. "I realized that I'd get nowhere unless I went back to the island for good."

In 1971, at age 29, Hyodo and his wife made the decision to throw away their careers in Tokyo and head home.

"There were about 40 of us," Hyodo recalled of the locals who shared his concerns over the logging, which had by then wiped out 80 percent of the original forest (monoculture cedar plantations were planted in their place). Those 40 got together in 1972 to form Yakushima o Mamoru Kai (The Association to Protect Yakushima).

Their message was that what little original forest remained should be preserved for future generations.

Hyodo, who ironically worked in the timber industry after his return (dealing only in plantation timber), chuckled as he recalled how he made signs to put on his invariably timber-laden truck: "Keep the original forests for the children!" and "Stop all the logging now!"

Still, the majority of Hyodo's neighbors, including his own parents and friends, were by then relying on the national government-funded logging industry for their livelihoods.

"I just wanted people to stop the logging for a moment, so we, the local people, could think about whether this was really the right thing to do," Hyodo remembered.

But the answer he got was always the same: "Stopping the logging isn't going to put food on the table."

However, what might be regarded as nature's own self-defense mechanism soon came into play. In 1979, Typhoon 16 hit Yakushima directly, causing landslides in 152 locations and damage to 231 houses — though fortunately without any loss of life.

As Nagai explained, "About 150 of those locations where landslides occurred were in the plantations where only cedar had been planted by the loggers."

In other words, the plantations then all-but blanketing the island were not capable of standing up to Yakushima's natural environment. The original forests were. So in the end, it was Typhoon 16 that made the majority of locals understand what was at stake — and just five months later one of Yakushima's two municipalities banned logging of original forests.

The problem was that the municipality had no jurisdiction to impose such a ban, as the forests were owned by the national government's Forestry Agency. Consequently, when the agency decided in 1981 that the last remaining tracts of Yakushima's original forests should be felled, the scene was set for a showdown.

"We had to take the discussion to Tokyo," Hyodo said. "We went to the Lower House of the Diet, the Upper House. We'd run around telling the members what was going on. We went to the head office of the Asahi Shimbun and to the Kyodo news agency as well."

What was at stake was the Segire River basin, at the west of Yakushima — an area that, as Nagai said, "was as close as there was to untouched forests on the island."

"The key was the public opinion, the media and academia. Universities and researchers would always support us," Hyodo said.

With the help of several university professors and, it turned out, some sympathetic ears within the Forestry Agency, a solution was eventually found.

On Sept. 20, 1982, the then Minister for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Kichiro Tazawa, agreed to visit Yakushima himself. A day later he declared it "a conservation area for academic reference" — the only classification that the Forestry Agency had that would involve the complete cessation of logging.

Nagai explained just how significant a victory this was. "To actually stop a (logging) plan like this once it has been announced is very unusual. The agency had already constructed the logging roads — this work had been part of their plans for years."

"And then the minister came in and stopped it at a stroke," Hyodo added, smiling.

A decade later, UNESCO's researchers came to survey Yakushima for possible citation as World Heritage Site — and the core area they eventually listed was the Segire River Basin.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.