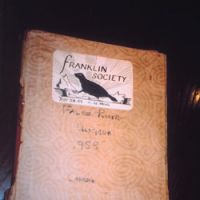

My eldest daughter Miwako visited me from Canada recently, bringing with her a large cardboard box full of old letters, field notebooks and field logs that had been stored away somewhere. The oldest of the notes was the log of my first expedition into the High North of Canada in 1958. I was 17 when I went there that time, 18 when I came out; so that log is 48 years old.

Since then I have always kept field notes (which are written for yourself), and on expeditions and long field assignments I have also compiled detailed logs (which can be read by others). As well as these two "serious" records, I have also written "naughty notes" that might include risque poems, jokes and funny stories. With this latest windfall from Canada, I now have an almost unbroken 50-year collection of notes, which -- unlike video or electronic data -- are all perfectly legible, even after all those years.

Among the contents of that cardboard box, I also found the following account of the beginning of that first expedition, written in retrospect when I had just finished my third expedition at the age of 22. In part, I wrote it to make fun of myself, and with the editor's consent, I'd like to share it with you here.

"Thoughts on an Arctic Explorer's Need for the Rugged Look," by C.W. Nicol; Devon Island, Northwest Territories, Canada; July 1962.

My first real conscious attempt at acquiring an appearance of ruggedness was in the fabrication of a fur hat. It was a sort of tatty round brown thing with flaps that looked like spaniel's ears. I was horrible at sewing -- great big stitches and lots of knots -- but you can get away with a lot if you're sewing fur. When finished, the hat looked like an impoverished Cossack grandfather's gardening cap.

I took my fur hat up to the High North with me on that first expedition in 1958, along with my fur-lined anorak, string vest and dispatch rider's breeches -- and I wore it all the time. The hat looked as if a racoon in the terminal stages of mange had clung to the top of my head to expire. Never mind that though, to me at the time, it was the epitome of ruggedness.

Mum's horror

I'm jumping ahead of the story.

I got the fur at a junk shop on the High Street in Cheltenham [a lovely and rather refined small city in western England], and sewed it up at home to the horror of my Mum, who objected to what she said were dog hairs (or whatever) getting in the butter. We'd been squabbling a bit about me wanting to run off to the Canadian Arctic, and I retorted that she should consider a couple of hairs in the butter a better thing than to have her son's head freeze solid.

"Just imagine," I said, "the skull bursting open as the brains froze, all for the lack of a furry hat!"

I was going off on an Arctic expedition, come what may, and I intended to do it properly. In those days polar heroes were supposed to be rugged. Maybe some of them weren't really and truly rugged, some might even have been on the wimpy side, but at least they had to look rugged in photographs.

One must learn to strike up a rugged, heroic pose -- and that takes practice. This was crucial if one wanted to be considered a real polar hero. After all, it would be no good to have your picture taken when you were scratching your bum or sniffing your socks, so you just had to develop that sense to leap into a rugged pose any and every time a camera pointed at you.

Rugged poses are one thing, but they won't work without the right props. Can you imagine a polar hero waving a can of underarm deodorant spray? Or with an umbrella? A poodle? No, no, no! It's got to be a furry parka, rifle, harpoon, dog whip, sled, husky -- or perhaps a polar bear if you can get one that's amenable. I started off with the hat.

Protherough (we called him "Poxy" because his initials were V.D.) went with me to get the fur, and it was largely through his efforts that we dickered the junk shop man down from 3 shillings and sixpence to 2 bob [from around 18p to 10p, or 45 yen to 25 yen].

I think old Poxy would like to have had the hat himself, but he would have looked silly waltzing around Cheltenham in it. It's just not the milieu. Mind you, one could find some funny headgear in Cheltenham. There was one chap who wore a green bowler around, until somebody at a jazz dance peed in it.

"What do you think?" I asked, putting the hat on after it was finished.

"It looks as if your head's got a disease," Vernon David opined.

"What do you mean?"

"Well, look at it, it's sticking out in lumps!"

"That's a stupid thing to say. How can you have lumpy fur? Fur isn't lumpy, it's bushy, or frazzled or whatnot -- but not lumpy."

"Yours is mate" said Poxy. "It's lumpy." He stared at me for a bit longer. "In fact, your head looks like a mushroom with fungus growing out of it."

There was no point in discussing it further. After all, if a bloke can't tell ruggedness from a mushroom, it's his fault, right?

I did have one lady friend called Nel, who split her sides laughing when I was foolish enough to show her the hat. But she made it up to me by knitting me a pair of long johns, woolly, and striped in 13 different colors, all of them hues most hideous. I cut quite a sight in my striped woollies, fur hat and string vest.

I'd rather not go into my Dad's reaction to my hat. That's the kind of thing that can only be retold to one's psychiatrist. Nonetheless, I packed the hat away, along with the plans for the expedition, the sailing date out of Liverpool, and concentrated on other preparations for ruggedness.

On this first expedition I was to be the assistant of Peter Driver, later to be Dr. Peter Driver, but we all called him Peemd. The expedition was to Ungava Bay [in northern Quebec], and in his first letters from Canada, he told me that we would have to cross the Koksoak River. This name, on first reading, struck me as quite dramatic, perhaps because I had been memorizing some verses of "Eskimo Nell" and had this compelling image of rugged polar types, all lining up along the banks of the Koksoak River in order to cool their afflicted doodles by dangling them in the icy waters. When I got there, I learnt that it wasn't pronounced that way, not even in French.

Living off the land

Peemd was into ruggedness himself, with a notion about living off the land -- which meant we headed off into the wilderness with rather few items of grub. Flour, salt, baking powder, tea, sugar, powdered milk, powdered eggs, one can of fat bacon and four cans of jam. That was to last us for months. If you told that to your average Canadian or Alaskan polar hero, he'd probably giggle. I didn't mind though. Lichen can be quite nutritious, as long as you pass it through a caribou's gut first.

We traveled from Fort Chimo with a local Inuit guide called Jobi Snowball. Jobi operated an open clinker-built whale boat with a gasoline engine that was held together by string and wire and had a great big flywheel that he spun by hand to get the engine started.

The most vivid memory I have of that trip is of getting my bum colder than it had ever been before. Mum would have been horrified. For years she had been warning me about the perils of sitting on cold steps, and there I was, sitting in a wooden boat with my bum less than an inch away from water that had great big lumps of ice in it.

My head, mind you, was quite warm -- albeit a bit itchy -- for at last I felt that was a suitable environment for wearing my fur hat.

Peemd hunkered next to me, and I suspect his bum was chilled too because he was extraordinarily irritable. I reckon that cold bums are worse than cold feet for making people cross.

The journey took all day, down the wide Koksoak, out unto Ungava Bay, along the coast, then up False River to a campsite which Peemd had selected from looking at the map. All the way our two Inuit guides grinned happily and potted at every seal foolish enough to show its head within range. Neither of them hit anything, but they giggled each time they missed, which at the time shattered my illusions of silent, solemn hunters patiently wresting their food from the harsh Arctic waters.

Instead of seal that day, we had tea and bannock. Bannock, the staple of the High North, is a 2-inch-thick [5-cm-thick] pancake made of flour, baking powder, salt and water. It's heavy enough to weigh down tent flaps, and is very filling. Usually bannock is a platform for jam, marmalade, peanut butter or whatever, but on that day we ate the bannock as it was. As I said, it was very filling.

The hot tea cheered Peemd up a little, because he finally condescended to talk to me.

"You look idiotic," he said.

"Oh thank you," I replied, scathingly sarcastic.

"Well, you do, what with that silly hat and the way you grin all the time. You are always grinning when the Eskimos are around. (We didn't know at the time that the Inuit didn't like that name). They probably think you're weak in the head."

"Well I must be," I thought to myself, "hunkering in the bottom of a boat with a grouchy old fart, floating around an icy sea with my bum freezing and getting insulted like this."

I could have retorted in a similar fashion about his balaclava with the pompom on top, but I thought better of it because he was bigger than me, and, as I said, very irritable at the time.

Greeted with enthusiasm

Instead, I decided to play my harmonica. That made our guides grin and Peemd grimace. My rendition of "Momma's little baby loves shortnin', shortin' " was greeted with enthusiasm by Jobi, but Peemd pulled his parka hood over his head and tried to disappear into it. I didn't think it was fair; after all, he played trombone, even though he didn't bring it along on this trip.

Along the journey we saw seals, all kinds of birds, and lumps of ice, but we didn't see the aurora [borealis] because it was daylight all the time. Peemd pulled a piece of tarpaulin over himself, maybe to get away from my cheerful harmonica music and hugely grinning audience of two.

We were very glad to finally reach our destination, there to stay for several months. More rugged tales to come.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.