“A priest who gives a sermon should be handsome,” wrote Sei Shonagon in her 10th-century classic “The Pillow Book.” “After all, you’re most aware of the profundity of his teaching if you’re gazing at his face as he speaks. If your eyes drift elsewhere you tend to forget what you’ve just heard, so an unattractive face has the effect of making you feel quite sinful.”

She was, at most, only half-serious. Tongue-in-cheek was her chosen mode. She’s been loved down the centuries for her sparkling, irreverent wit. She was a court lady in an empress’ service; she wrote for her fellow courtiers’ amusement and her own — not for ours; surely she never thought of surviving her own time; nor could she have even begun to conceive of life as we live it; but that’s neither here nor there; reading her today, we get the impression that religion in her day was more decorative than elevating, more frivolous than awesome.

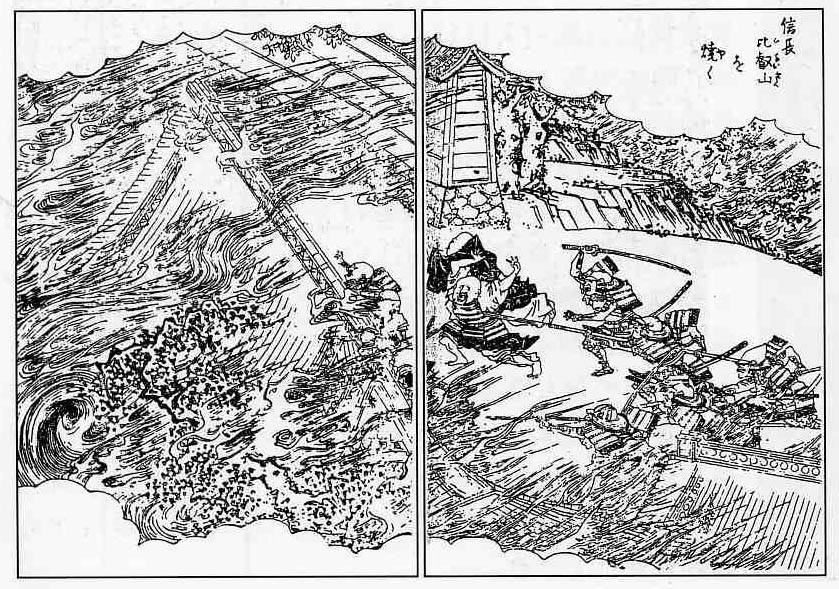

Other ages lived on a sharper edge, and produced priests to match. There is the priest Mongaku, a terrifying character, anything but handsome, who figures in the 12th-century epic “Tales of the Heike.” We first meet him deep in the practice of austerities only the god-inspired — or Buddha-inspired — can contemplate, let alone endure. Hunger and thirst are nothing to him; pain is pleasure; heat and cold torment the body but beckon the soul upward toward enlightenment. A well-meant attempt to save him from certain drowning under a freezing waterfall in mid-winter draws from him, when he regains consciousness, a withering rebuke: “I am under a vow to stand under the waterfall for thrice seven days and repeat the magic invocation of Fudo three hundred thousand times, and today being only the fifth day who has dared to pull me out?” On hearing which, “the hair of (his would-be rescuers’) heads stood up and they could say nothing.” What would Sei make of him?

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.