Last week, officials from the highest levels of the Japanese and U.S. governments met in Washington.

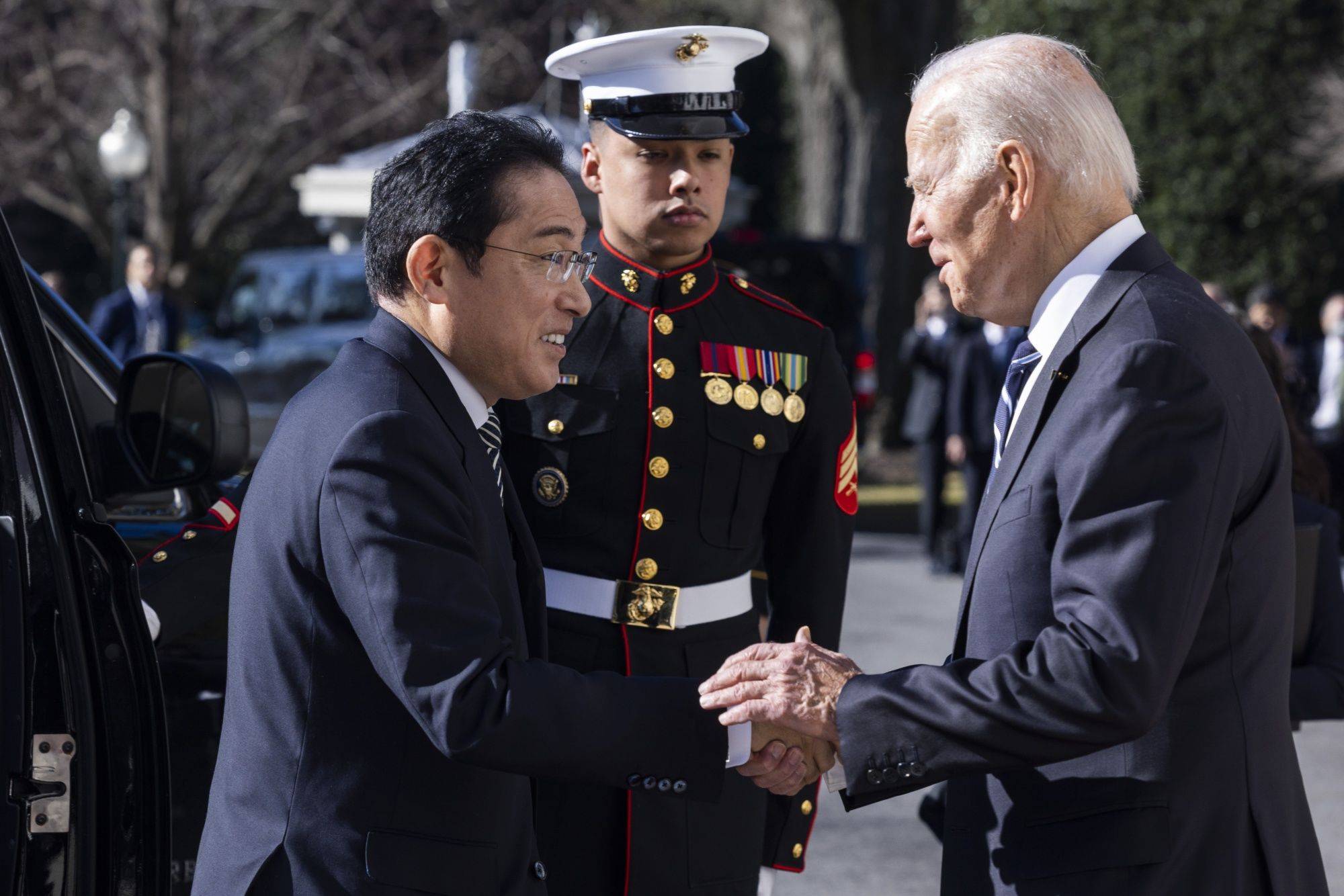

On Jan. 11, the two governments held a "two-plus-two” defense and foreign ministerial meeting and two days later came the summit between Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and President Joe Biden.

Sprinkled throughout the multiday visit were other political and social engagements, all centered on promoting Japan’s role in tackling global issues and advancing myriad Japan-U.S. initiatives. With so much activity going on during the trip, one may reasonably wonder what to make of it all. Was there any substance to it? What were the key outcomes? What does this mean moving forward?

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.