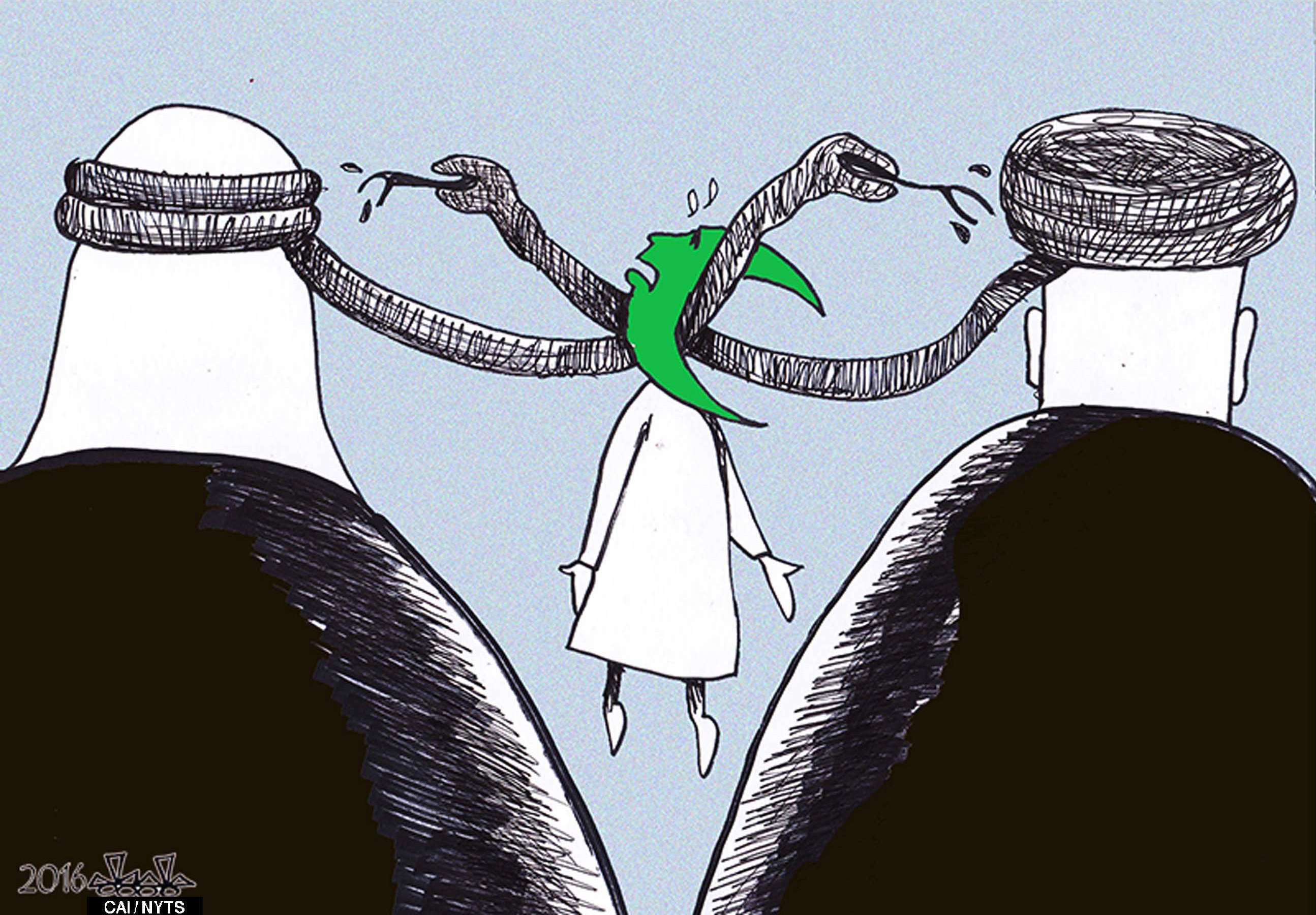

In Lebanon today, all the symptoms of the Middle East's current turmoil are visible. Newly arrived refugees from Syria and Iraq are joining Palestinian refugees who have long been here. The country hasn't had a president for two years, as rival political factions, reflecting the rising enmity between their Iranian and Saudi Arabian backers, are weakening domestic governance. Political corruption runs rampant. The garbage doesn't always get picked up.

But Lebanon also shows signs of resilience. Investors and entrepreneurs are taking risks to start new businesses. Civil-society groups are proposing and implementing useful initiatives. Refugees are going to school. Political enemies are collaborating to minimize security risks, and religious leaders advocate coexistence and tolerance.

Lebanon's resilience owes much to the memory of its painful civil war (1975-1990). By contrast, the rest of the region's experiences — which involve a long history of autocratic governance and neglect of long-simmering grievances — have fanned the flames of conflict. Syria, Iraq and Yemen are now riven by war. Meanwhile, the Palestinians' worsening plight is still a perennial grievance on the Arab and Muslim street. In this maelstrom, new radical groups with transnational agendas are blossoming.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.