In the summer of 1281, Kublai Khan sent a massive fleet of over 4,000 vessels carrying more than 140,000 soldiers to invade the Japanese archipelago — the second such attempt by the Mongol ruler after a previous mission in 1274 failed.

Intense maritime battles ensued on the seas and islands of northern Kyushu, with fierce resistance from the Japanese eventually leading to a military stalemate. Legend has it that as the Mongol forces docked in Imari Bay, a monstrous storm stirred up hulking waves and devastated the ships. The typhoon has since been mythologized as kamikaze, or “divine wind.”

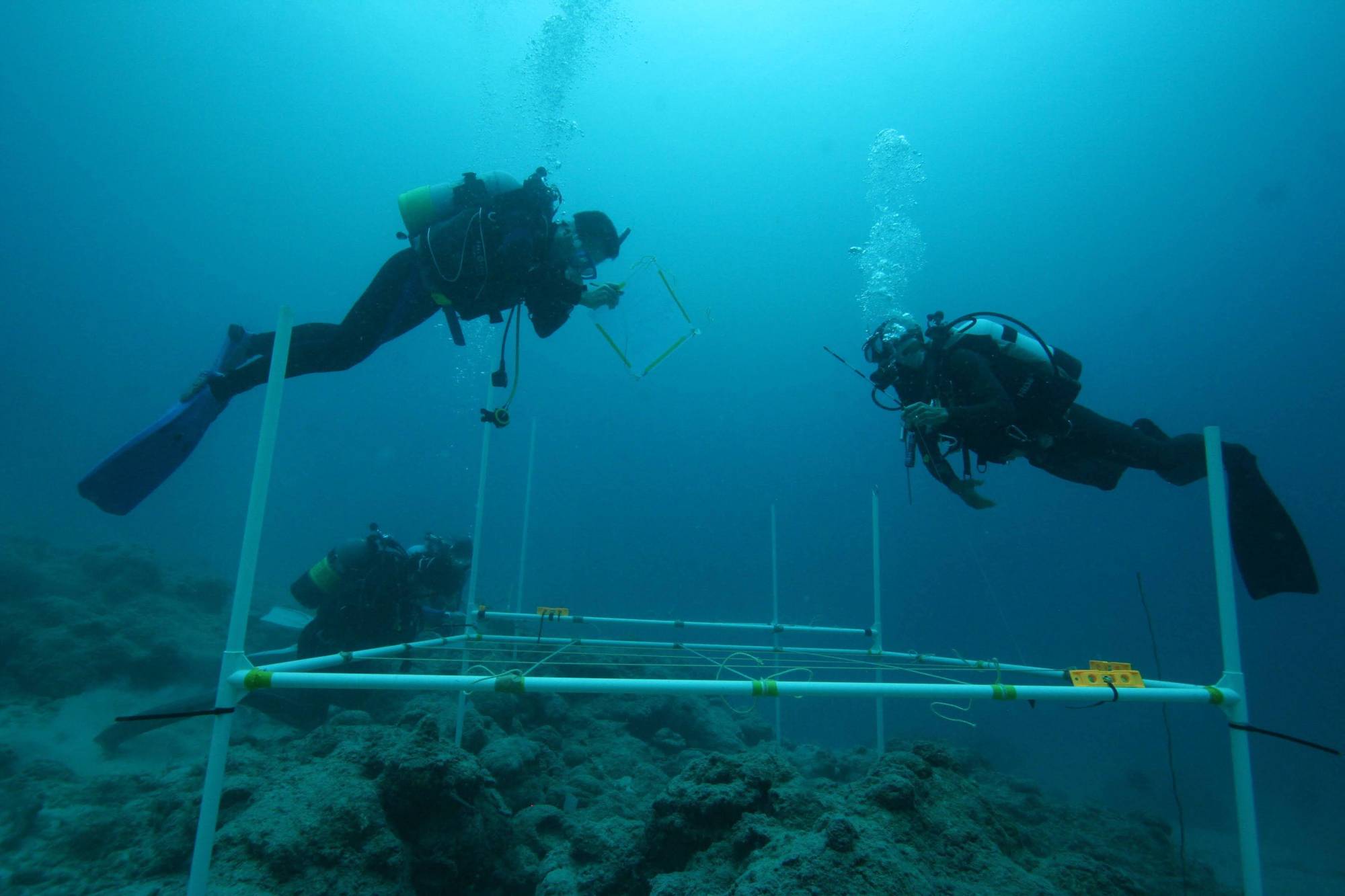

It is here, off the southern shores of the island of Takashima at the mouth of the bay, where ancient remains of the conflicts have been found, after being submerged in darkness for centuries.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.