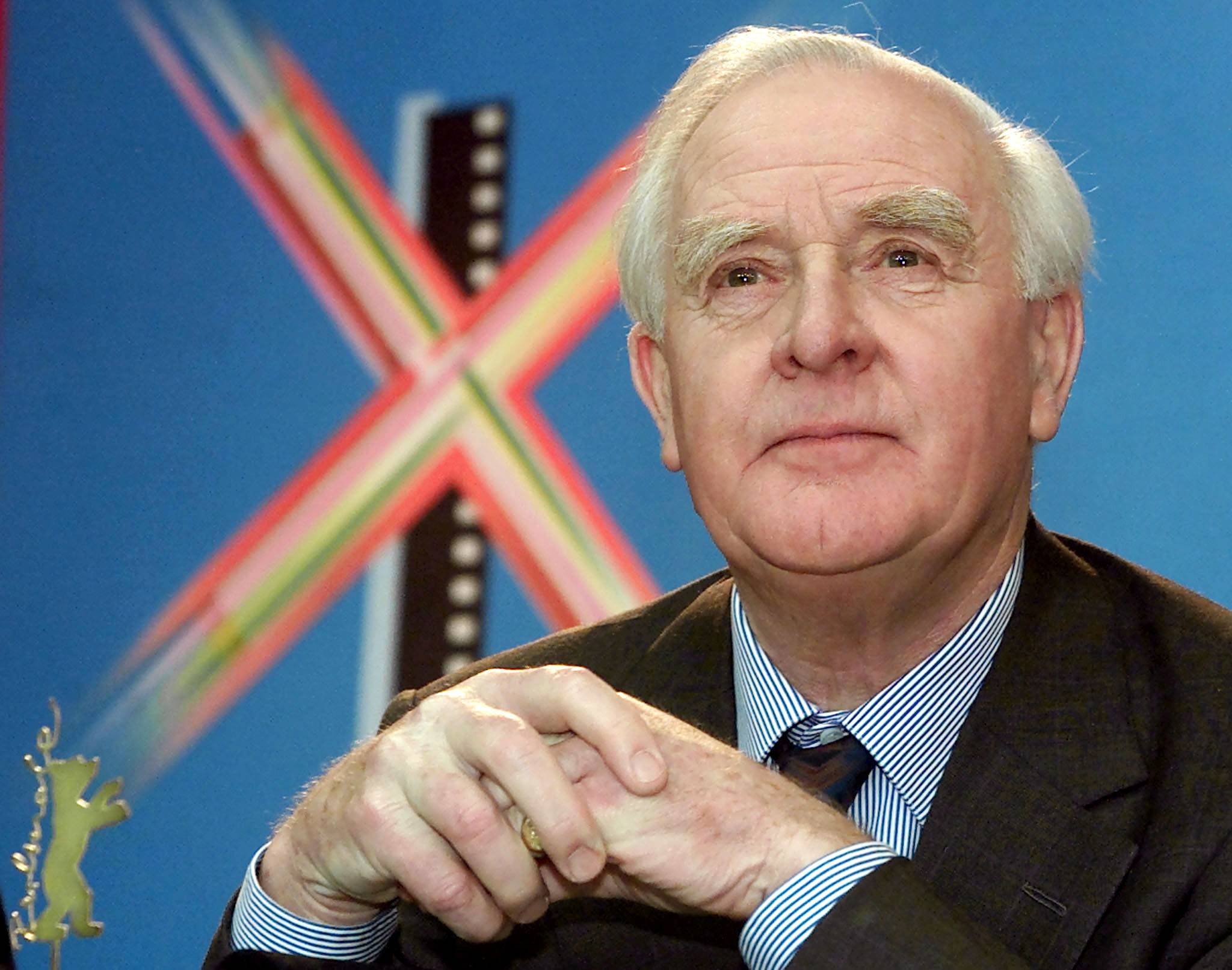

David Cornwell died last week at the age of 89. As John le Carre, Cornwell transformed the spy story. His New York Times obituary credited him with “Cold War thrillers [that] elevated the spy novel to high art by presenting both Western and Soviet spies as morally compromised cogs in a rotten system full of treachery, betrayal and personal tragedy.”

Le Carre’s "heroes" were the antithesis of the spies who dominated the popular and cinematic imagination. They weren’t cartoon action figures, whose shot and chaser was a bullet and a beverage. Instead, explained the Times, they were “lonely, disillusioned men whose work is driven by budget troubles, bureaucratic power plays and the opaque machinations of politicians — men who are as likely to be betrayed by colleagues and lovers as by the enemy.” While le Carre gets the credit, other writers — Len Deighton (my personal favorite) and Brian Freemantle, to name two — created similarly cynical, rumpled and gray characters, who were much more than they seemed and never failed to best their establishment “betters.” That was often a result of their insight into and understanding of the human condition, born of — or perhaps responsible for — that inferior social status. They recognized and knew each other in an encounter — unlike their superiors, who never saw the threat they posed.

To call these protagonists "heroes" requires some work. They are the good guys because they look like us; accordingly, we credit their intentions and dismiss their flaws. They are also British, which means that they plied their craft in the service of a country that was struggling to remain relevant — one that had, in Dean Acheson’s reckoning, “lost an empire and failed to find a role.”

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.