Unless you follow politics closely, you could be forgiven for thinking that Hillary Clinton has locked up the Democratic presidential nomination. This is not true. She still doesn't have the requisite number of delegates. That could, and probably will, happen next month when her lead in superdelegates puts her over the top at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia — when the superdelegates actually, you know, cast their actual votes.

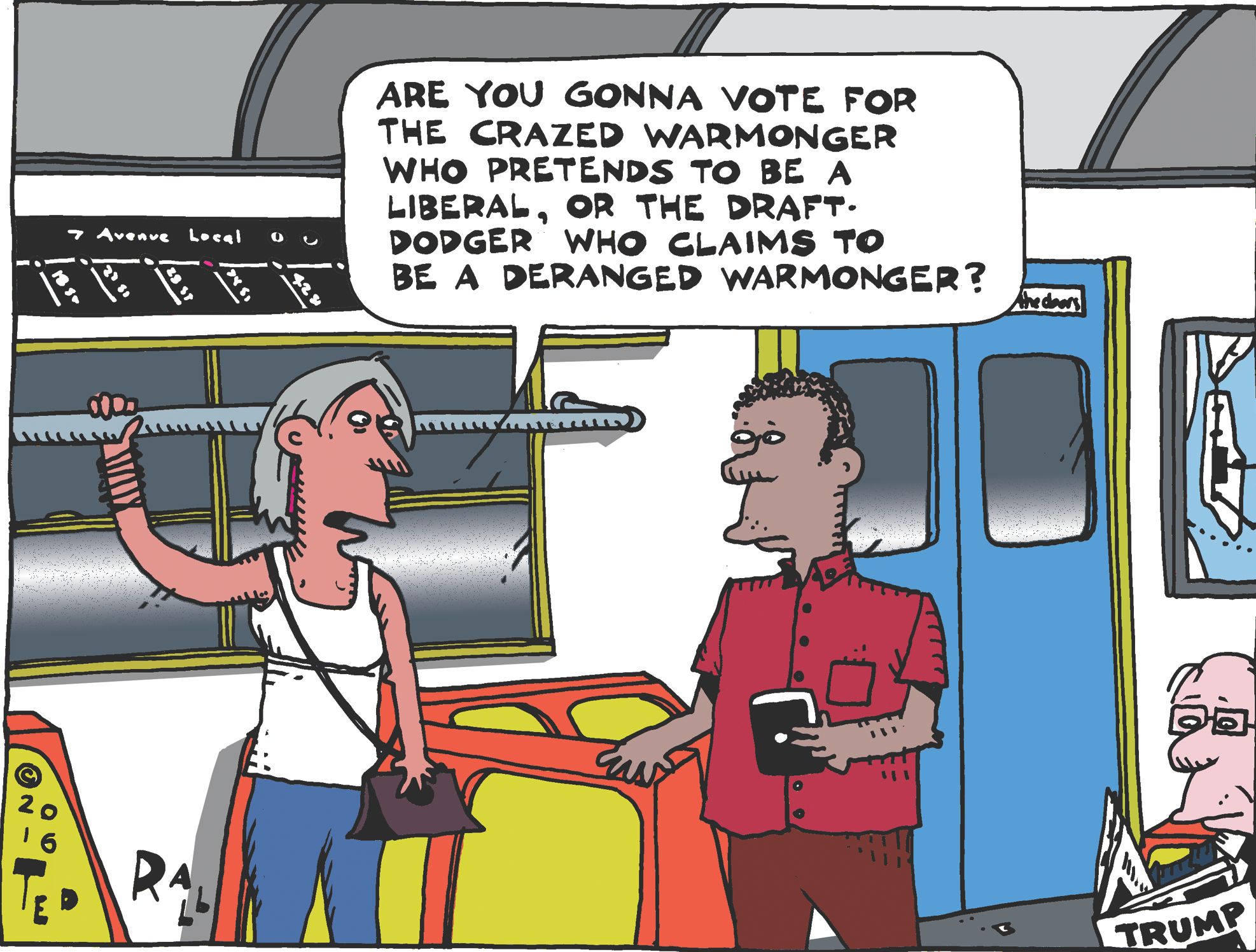

The media, however, doesn't want you to know that Bernie Sanders is still in the race. And so, based on that flimsiest of measures — an opinion survey of superdelegates who are allowed to change their mind at any point before July's DNC — they've called the Democratic race for Clinton. This completely illogical reasoning logically leads pundits to the question of the month: How can the Clinton campaign convince progressive supporters of Sanders — whose race was largely based on the assumption that Clinton is so far to the right that she might as well be a Republican — to vote for her?

Every four years mainstream political writers and commentators push Democrats to the right after the primaries, arguing that swing voters decide presidential elections. Like trickle-down economics, however, that doesn't seem to have been true any time in the recent past. Political parties seem to perform best when they motivate their base to turn up at the polls. Given the fact that Republican voters are congenitally more likely to fall in line behind their nominee, even if he turns out to be a proto-fascist, than Democrats, it's obvious that Clinton will need as many Sanders supporters as possible in November if she indeed becomes her party's nominee.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.