Shinichi Gibo survived the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 at the age of 6, but he has lived with a persistent trauma ever since.

As a war orphan, he felt a deep sense of loneliness and inferiority. "There are no dreams, no hopes. Why is life so painful?" the now 86-year-old recalls thinking while growing up.

When Gibo was 3, his father died of illness, and his mother left him behind to work far from home. He was raised by his aunt and uncle, and together, they fled through the fierce battleground in southern Okinawa, stepping over corpses as they ran.

Eventually, the family was sent to an internment camp in the village of Ginoza, where his uncle and aunt died after consuming food contaminated with DDT, an insecticide sprayed by American soldiers.

With that, Gibo became one of the many children in Okinawa who lost their guardians to the war.

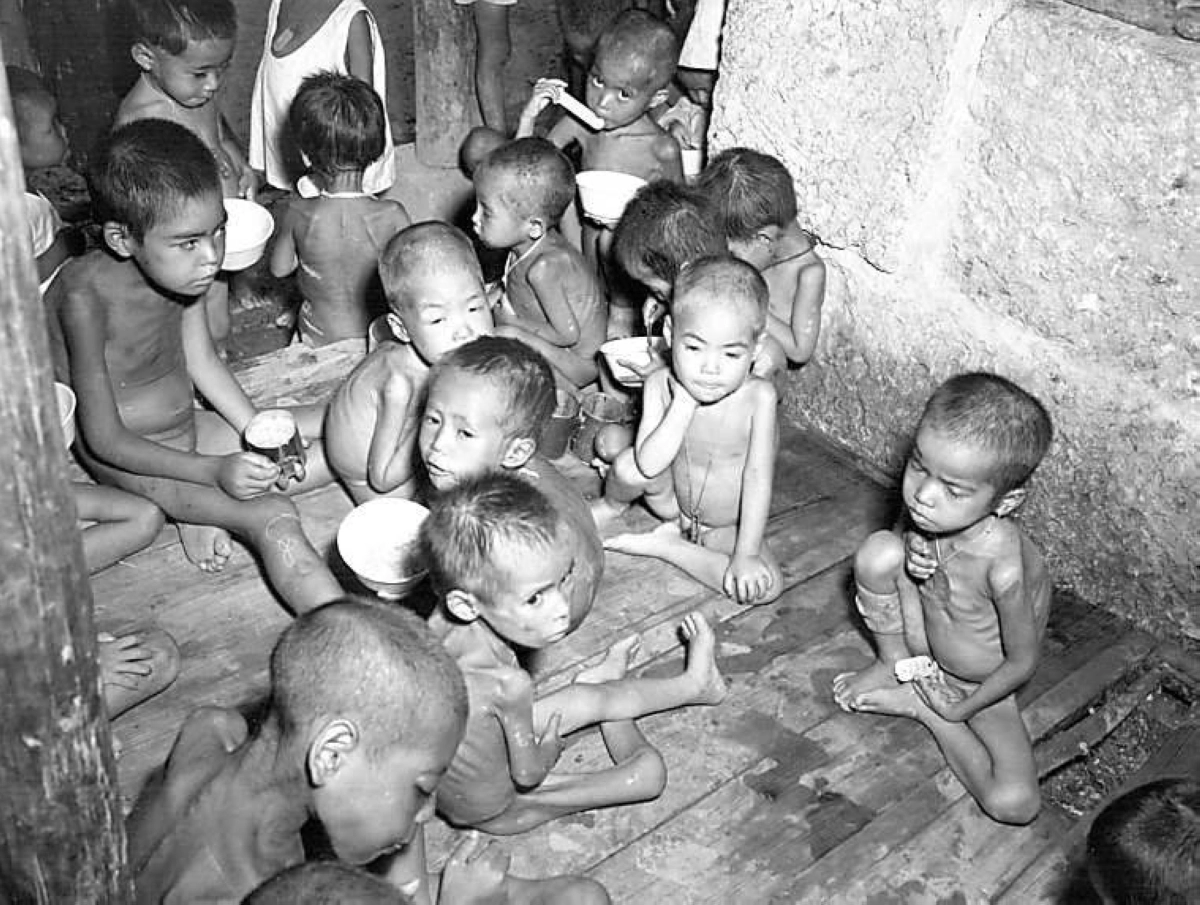

The U.S. military established 14 orphanages in civilian internment areas. However, these facilities merely provided shelter, and children were largely neglected. In dire conditions, many died from starvation or broke down with malnutrition or disease.

Even under such harsh conditions, Gibo managed to survive in an orphanage in Ginoza. He was later transferred from one child welfare facility to another. "There were so many children in every institution, but all I thought about was how to survive,” he said. “Everyone seemed like an enemy to me."

At age 18, he was forced out of the last welfare facility he lived in. Then he drifted, frequently changing jobs. Years after the end of the war, memories of the battlefield — women with their legs blown off, bloated corpses and the stench of death — still haunted him, often causing nightmares.

The experience of fleeing the battlefield and the loneliness in his childhood made him feel inferior, said Gibo, who now lives in Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture.

It was only in his 40s that he found some emotional stability. He discovered faith, built a family and found salvation. "I was alone for such a long time," he said. "I never want to feel that lonely again."

Marginalized

Akira Kawamitsu, 65, a lecturer at Okinawa International University, noted that war orphans like Gibo were either placed in orphanages, taken in by relatives or acquaintances, or wandered around as street children. “War orphans were pushed to the margins of society after the war," he explained.

Statistically, the number of such orphans decreased over time, and they became socially invisible. However, there was no thorough investigation, and the full extent of the situation at the time remains unknown.

Among the people who shared their experience as war orphans with Kawamitsu is a woman who was 7 years old at the time of the battle in 1945. She was taken in by relatives but was made to work as a laborer doing house chores such as cleaning and fetching water.

Another woman, also 7 at the time of the battle, told Kawamitsu that her experience of being mistreated by relatives felt worse than being bullied by strangers.

Many war orphans suffered from harsh living conditions and overwhelming loneliness, Kawamitsu said. “Their trauma of war was compounded by the trauma of postwar hardship."

The war left countless orphans and single-parent families not only in Okinawa Prefecture, but across Japan.

In mainland Japan, the Child Welfare Law was enacted in 1947 to help impoverished children. Mother-child shelters and child care facilities were established one after another.

Lagging child welfare

In contrast, Okinawa Prefecture remained under U.S. military rule for 27 years after the war. The prefecture’s own child welfare act was enacted in 1953 — six years later than in mainland Japan — but it was not until 1974 after Okinawa's reversion to Japan that the first mother-child shelter was established. After-school care facilities for children only appeared in 1978.

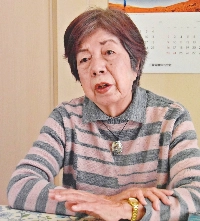

"Postwar Okinawa was not a society where children could grow up with a sense of security," says Yuko Yamauchi, 77, who worked for over 30 years in child consultation centers and other welfare facilities to help children and women in dire situations.

In Okinawa Prefecture, juvenile delinquency increased as child welfare policies lagged behind. According to Okinawa’s police history, 885 juvenile offenders were arrested in 1951, but the figure nearly tripled to 2,350 in 1967. The number of serious crimes rose from single digits shortly after the war to 253 in 1968, which broke down to 12 murders, 133 robberies, three arsons and 105 rapes.

Ryoji Aritsuka, 78, a psychiatrist who has treated Okinawa Prefecture's war survivors, says juvenile crimes may have been triggered by the stress children carried from the war, their postwar deprivation and the various societal difficulties they faced later in life.

Yamauchi, the child welfare expert, notes that emotional scars left in war orphans were particularly deep.

One woman that Yamauchi met at a women's consultation center in the 1980s was suffering from an identity crisis after being orphaned by the war.

As a child, the woman was taken prisoner by U.S. forces and was placed in an orphanage. She was later taken in by someone she didn’t know, but she could never feel secure.

The woman told Yamauchi that she would often look at passersby and wonder if they could be her parents or siblings. Throughout her life, she searched for her roots, wandering across Okinawa in hopes of finding her kin.

"Not knowing who you are means losing your identity," Yamauchi said, explaining the heavy emotional burdens carried by war orphans.

"The people of Okinawa, who were caught in a battleground, continued to be tormented by U.S. military bases after the war,” Yamauchi said. “Both adults and children were unable to heal from the emotional wounds inflicted by war."

Under U.S. military rule, Okinawa lacked the necessary social infrastructure. The fallout from the poverty experienced by many citizens in the postwar period still lingers in Okinawan society.

Yamauchi laments that, even today, poverty is often the root cause of social problems such as juvenile delinquency, child abuse, domestic violence and divorce. “Poverty takes shape in different ways behind various problems,” she said.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.