Robert Moses, the civil servant who built the great park-expressway-bridge network in New York state during the middle of the last century, succeeded by gaming the system. Understanding how politics would make it difficult for him to fulfill his vision, he often started a public works project clandestinely. By the time it was presented to regulatory scrutiny, it was already partially done, so elected officials had no choice but to approve it.

This underhanded method lent Moses the reputation of a man who got things done, but it also allowed him to sidestep checks and balances, which is why he is blamed for the urban blight and full-time traffic congestion that afflicted the New York metropolitan area after World War II.

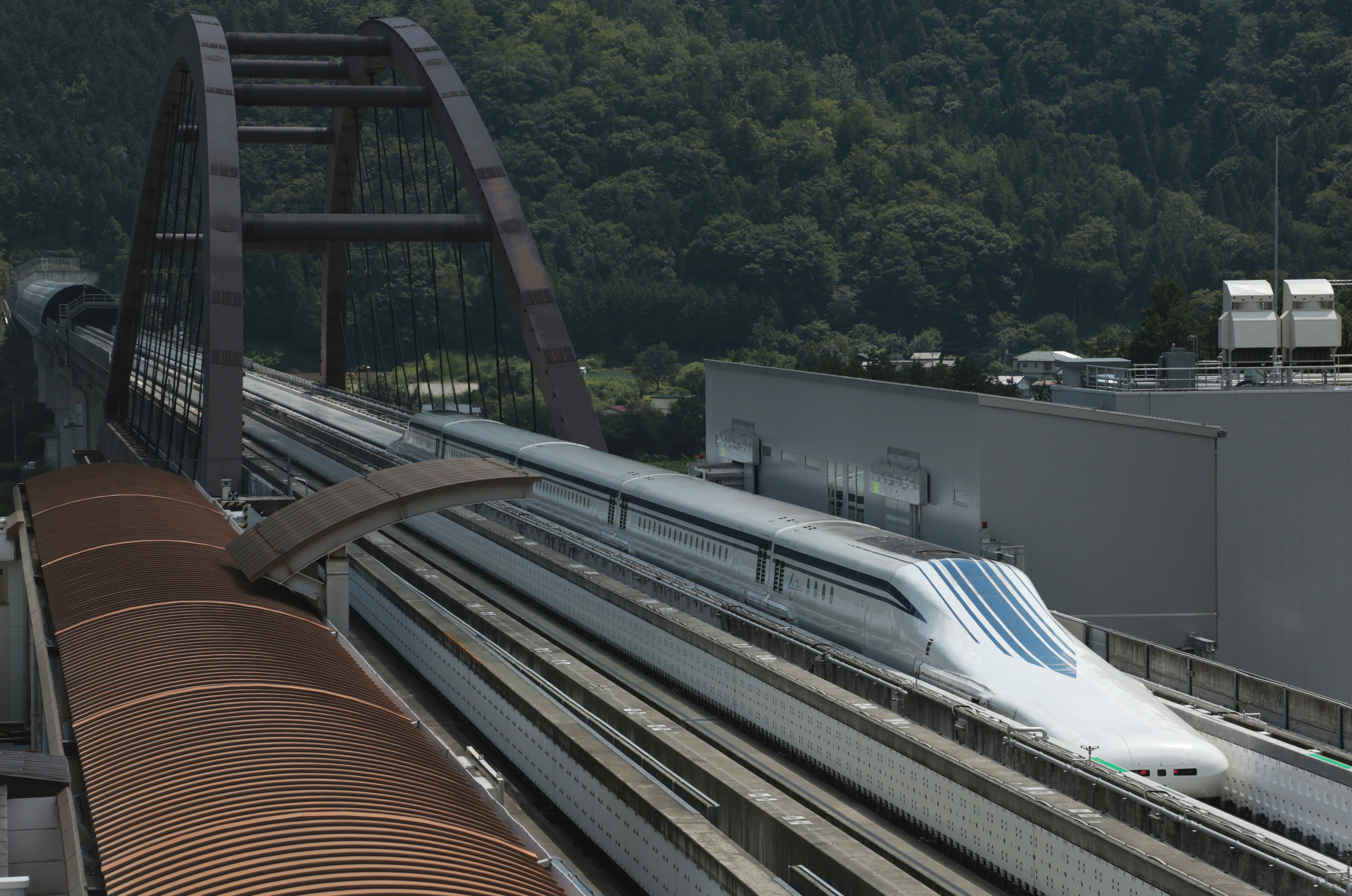

World-renowned management consultant Kenichi Omae doesn't mention Moses in his critique of JR Tokai's (Central Japan Railway Company) magnetically levitated shinkansen, published in the Aug. 4 online edition of the business magazine President; but when he describes the company's chairman, Yoshiyuki Kasai, it sounds like Moses' infamous arrogance. Omae imagines Kasai as saying, "We are paying for this, so the government and the bureaucracy don't have any say in the matter." Though the maglev is a massive public works project that will affect all of Japan, JR Tokai doesn't think it needs central government approval since it isn't asking for money. The ¥5.43 trillion needed to connect Tokyo and Nagoya will be borne by the company.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.