Smoke curls into the sky from power plants, home heaters, factories and cars, poisoning the air. Rain runs in sheets off slopes stripped of trees, eroding valuable topsoil, sedimenting rivers, causing raging floods downstream, and later, droughts as land loses its capacity to hold water.

More than one-quarter of China has succumbed to desertification, the amount of waste produced doubles every nine years and the population continues to climb, albeit slowly.

China is a big country with big environmental problems.

As the world's most populous country undergoes the wrenching transition to modernity, it is struggling to balance environmental concerns with economic growth.

Increasingly, both the government and researchers in Japan are turning their attention to environmental problems in China.

Masayoshi Sadakata is one researcher visible in the debate. The professor from the University of Tokyo's Department of Chemical System Engineering is determined to clean up China's air while reclaiming land on the verge of desertification.

It is a tall order, but Sadakata and colleagues are nonetheless confident they can develop a sulfur-removal system that could cut China's sulfur oxide emissions, which cause acid rain, by more than 15 percent.

"Burning coal leads to acid rain, which encourages desertification and erosion that leads to runoff, poor water quality and floods," he said, indicating that China's environmental problems are intricately interrelated and also have ramifications for Japan.

Sulfur-removal technology is established in Japan but does not travel well. The Japanese technology is water intensive, while much of China is strapped for water.

"Japan has often transferred technology to developing countries, pushing it on them, only to find it doesn't put down roots," Sadakata said.

The technology he is fine-tuning with China's Tsinghua University uses one-tenth the water of conventional methods and combines sulfur emissions with calcium to make gypsum, which rehabilitates alkaline or acid soil.

Sadakata and company hope that with a little tinkering, the technology can be made commercially viable in China.

"Right now, in China everything is about money. If we can make this profitable . . . then (the technology) should spread."

If implemented on a large scale, enough gypsum could be produced to resurrect 7,000 sq. km of farmland a year, countering that gone barren, he said.

"It is important to meet the needs of the Chinese, supplying technology that they can use, not imposing it upon them," Sadakata said. He indicated that the lack of water and high operation costs have doomed previous efforts to failure.

Everyone's problem

Clearly, China's problems are the world's problems.

Air pollution is impacting Japan and others in the Asian neighborhood. Water pollution flushed down major rivers may already be affecting Asia's fishing grounds. Some even speculate that if China does not reconcile its economic growth with natural limitations, it could trigger a flood of environmental refugees.

"China is in a terribly difficult position," said Hideaki Koyanagi of the Environment Ministry.

The sheer variety of problems is daunting, said Koyanagi, who spent more than three years working at the Sino-Japan Friendship Center for Environmental Protection in Beijing.

"China faces major water and air pollution problems -- ones that Japan has already resolved -- while also having to deal with modern problems, like dioxins and global warming," Koyanagi said.

Echoing this view, Masato Watanabe, an official with the Japan International Cooperation Agency who has worked in China, maintains that helping China resolve environmental problems is in Japan's interest.

"Right now, environment is the key word in terms of ODA and will be for a while," Watanabe said.

The figures bear him out.

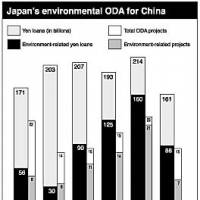

More than a quarter of the Japan Bank for International Cooperation aid projects in 2001, worth 161.4 billion yen, went to China. Seven of the 15 projects and 54 percent of the funding were environment-related.

China ranks only behind Indonesia in yen loans extended. Aid to China started in 1979 and the first environmental project was approved in 1988. Since then, there has been a major shift from infrastructure-intensive projects like railroads and ports to air and water improvement projects.

The Chinese government has also changed.

In the last few years, Beijing has started taking a more aggressive tack on approaching environmental threats.

A government reshuffle in 1998 upped the rank of the environmental chief to the equivalent of minister. In its new five-year plan released earlier this year for economic and social development, the government pledged an across-the-board cut in pollution by 10 percent and 20 percent in regions with heavy pollution.

Meanwhile, China has pledged to boost the nation's greenery from a paltry 13.9 percent in 1999 -- less than one-fifth the greenery of verdant Japan on a percentage basis -- to 18.2 percent.

China's leaders -- such as Jiang Zemin when he presented the ambitious plan to develop the nation's rural western region -- have even started to intone the sustainable-development mantra.

Conflicting interests

Pollution-related problems combined with economic development assistance has opened a new avenue for cooperation and cementing positive ties between Japan and China.

However, there is an element of ambivalence -- an emotional tug of war over supplying aid to an economic competitor viewed as ungrateful at times.

"There are things that China would like to do, and things that Japan would like to do. What we have to do is find programs that will be a plus for both countries," maintains Naohiro Kitano, director of Chinese development assistance at the Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

"Environmental items are meaningful for both countries and easy for both to understand because they help both countries," Kitano said.

But despite celebrating 30 years of normalized relations this year, the two countries have only just started to cooperate on the environment.

In 1988, leaders of both countries agreed to set up the Sino-Japan Friendship Center for Environmental Protection in Beijing. But it was sidetracked by the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 and other events, and it only got off the ground in 1996.

Earlier this month in Beijing, officials and researchers discussed ways of fighting scourges like desertification and yellow sand -- loose soil particles that get kicked up by the wind -- as well as newer problems, such as waste disposal.

Yet the upsurge in awareness that these countries need to collaborate on the environment is tempered by the independent interests of each and their blossoming economic rivalry. The scope of cooperation between the two countries is growing, but priorities differ.

"For Chinese people the water issue -- both quality and quantity -- is very important. It is a health issue. But for Japanese, air pollution and acid rain are of central interest," Watabe said.

Both sides hope that bridging these divergent interests could alter the trajectory of China's development and limit the environmental fallout on Japan and others.

Mutual benefits

Toward this end, bilateral collaboration between experts is increasingly visible as they work to think up schemes -- whether a satellite monitoring network or sulfur filtration technologies -- to help China avoid some of the pitfalls Japan has experienced.

For Japan, yellow sand, known to reach continents on the opposite side of the world, is likely the most poignant issue.

Last year was one of the worst on record as yellow sand measurably damaged air quality.

Akin to Sadakata and sulfur-removal his mission, Masataka Nishikawa and his research crew at the National Institute for Environmental Studies are tackling the slippery and diplomatically testy problem of yellow sand.

Frustratingly, is still not clear where exactly it comes from, how it reaches Japan, or how to stop it.

"The yellow sand that occurs in China is increasing annually," Nishikawa said.

And while the effects are becoming more visible here, it is Beijing and rural areas of China that bear the brunt of the blinding sand storms, killing hundreds annually, Nishikawa said.

"You can't take measurements in these (yellow sand storms). They are really scary," said Ikuko Mori, who works under Nishikawa.

Mori recently succeeded in "fingerprinting" sand from China for the first time. This could lead to identifying the origin of yellow sand and help determine where action, such as tree planting, should be taken, she said.

If the health of the citizenry is not reason enough to tackle the problem, the 2008 Olympics is. After failing to land the Games in the 1990s, Beijing rebounded with renewed vigor, pledging to clean up the city for 2008.

The Tianmo Desert is roughly 60 km from the capital and encroaching fast. It is not uncommon for sandstorms to force Beijing International Airport to shut down.

"Air pollution was a reason (that Beijing) failed to get the Olympics the first time, and cleaning it up has become a serious slogan for 2008," Nishikawa said.

China watchers liken the games to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics -- a coming-of-age event to catapult the nation into modernity.

At least as serious as air pollution, water is a grave, but largely domestic, concern.

Forty-four percent of sites where measurements were taken along the nation's seven major rivers showed water not up to the standard for agricultural use, let alone human consumption.

Erosion caused by deforestation has exacerbated the poor quality of the mighty Yangtze River, the world's third largest.

The Yellow River, which Motoko Hara, a professor in the economics department at Ryutsu Keizai University, said "was simply known as 'the river,' " earned its newer name when it became clouded with dirt due to erosion, overgrazing and runoffs upstream.

An expert on agriculture and Chinese civilization, Hara contends that it is only in the last 100 years that the soil has been ravaged, as traditional agriculture gave way to less sustainable crops.

She also believes that the government's plans -- such as subsidizing farmers in overburdened areas to put away the plow and plant trees -- are moving in the right direction.

If it plays its cards correctly, China could remedy many of the environmental ills plaguing it, according to Hara.

Unquestionably China will develop, increasingly impacting Japan. To what extent depends how the two work to resolve the dilemmas of the environment and development.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.