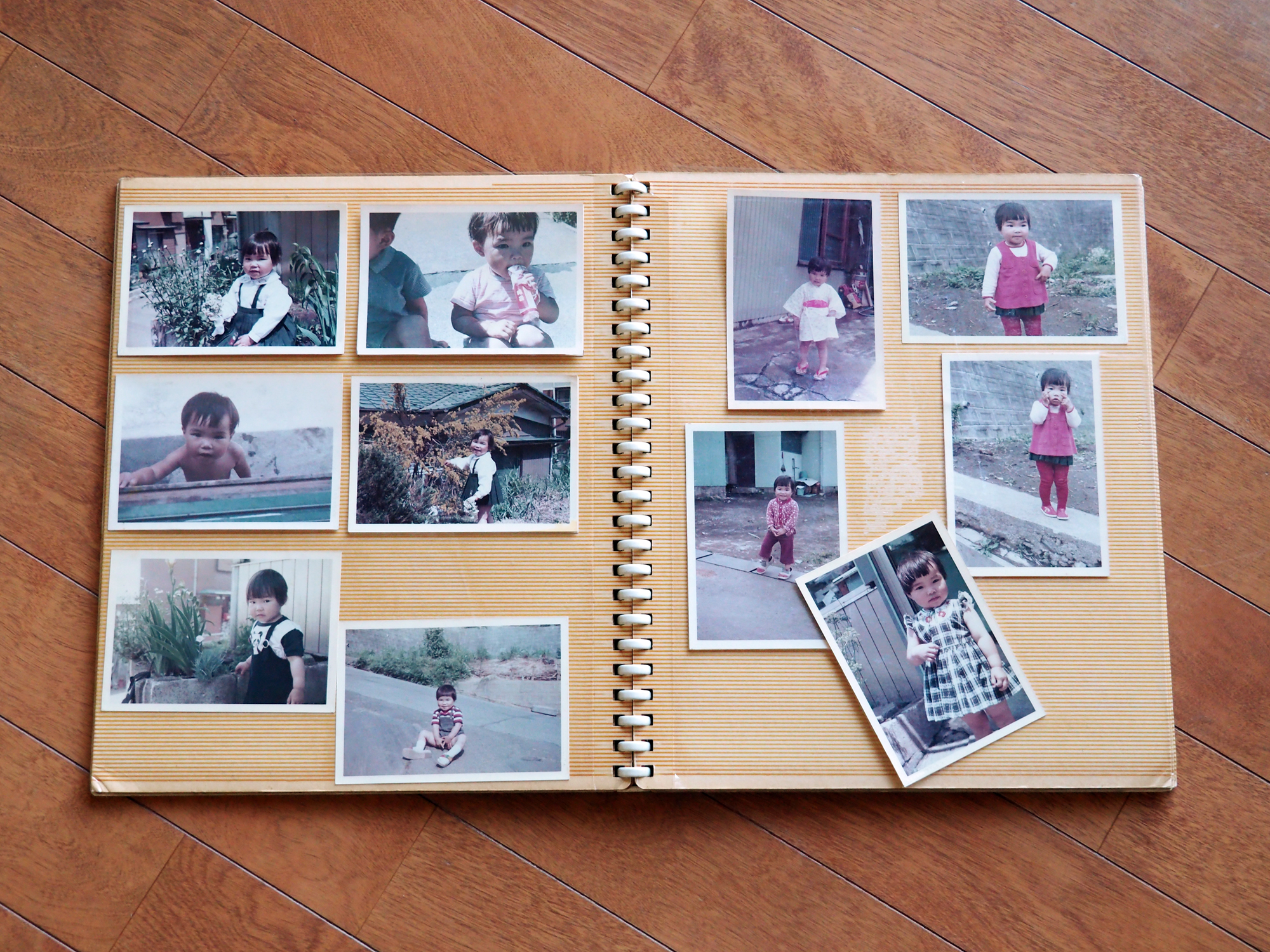

For many Japanese people, life is divided into two distinctly historical time lines: before and after the 昭和期 (Shōwa-ki, Showa Era, 1926-1989). 昭和の匂いがする (Shōwa no nioi ga suru, "This smells like Showa"), we say to each other, when talking about anything retro or 懐かしい (natsukashii, nostalgic).

Even the ゆとり世代 (yutori-sedai, "relaxed generation" — those in primary school during the education ministry's "relaxed education policy"), who were mere babies or weren't yet born dig Showa, as witnessed by their love of Showa dishes like スパゲッティナポリタン (supaggetti Naporitan, spaghetti Napolitan) and メンチカツ (menchi katsu, deep-fried minced meat patties), and 昭和ポップス (Shōwa poppusu, Showa pop music) from Keisuke Kuwata and Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Any discussion of Showa precludes the presence of Emperor Hirohito, who in early 1989 succumbed to illness after a 64-year reign. The nation then mourned the passing of a beloved but controversial icon who symbolized both Japan's ill-fated entry into World War II in 1939 and its exit in 1945.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.