The last job I had that paid me a real salary was with the Canadian government's Environmental Protection Service in the mid 1970s.

Back then, as an Emergency Officer responsible for the Pacific west coast and British Columbia, I had a very fine office in Vancouver, with a view of the inner harbor, Stanley Park and the Lion's Gate Bridge; if I looked down, it was to the Capilano River, a clear, fast salmon stream.

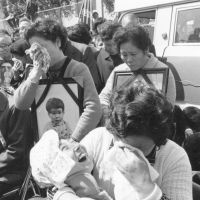

I had a black-and-white poster on the wall of that office, just one. It was a study by the acclaimed Magnum photographer Eugene Smith of a Japanese mother holding her crippled daughter in the bath — and it remains one of the most moving photos I have ever seen. Under it I had printed the words: "Remember Minamata."

There were some people who thought that image was inappropriate for the office of a Canadian government officer, but I disagreed.

I argued that the Minamata disaster was a lesson for the whole world, and that if we did not rigorously protect the environment, then untold suffering would be the result.

I became aware of a disease afflicting people in the Minamata area of Kumamoto Prefecture during my first sojourn in Japan in the early 1960s. It was a mysterious sickness of unknown origin that first affected cats, then humans, in that part of Kyushu — and which first become known to the public through an announcement made by a doctor at the company hospital of Shin Nihon Chisso Hiryo (New Japan Nitrogenous Fertilizer Co.), a major chemicals firm with a plant in the area. On May 1, 1956, that doctor, named Hajime Hosokawa, had reported an "epidemic of an unknown disease of the central nervous system."

Cats lost their sense of balance and twitched pitifully before dying, but it was among humans that the most awful sufferings began to present themselves. Victims would tremble uncontrollably, experience numbness in their limbs, tunnel vision, horrible convulsions and great pain.

In the early days some doctors postulated that it was a new kind of epidemic affecting the central nervous system, while others said it was a hereditary disease. There was terrible, and totally unjust, prejudice against victims. People could not change jobs, were refused marriage, were socially shunned. Even today, some of that prejudice lingers on.

I think that if I had been living in Minamata then, I would have soon found clues in the dead fish floating in the river and the bay, and in the filthy effluent being discharged from the chemicals factory, right where fishermen tied up their boats.

I have no doubt that both Shin Nihon Chisso Hiryo (whose name was changed to Chisso Corp. in 1965) and the Japanese government were fully aware of the real cause of the sickness from very early on, However, it wasn't until 1968 — 12 years after the first recorded case — that the government finally declared that the cause of the disease cluster around Minamata was pollution from the Chisso factory. All those years — and back since soon after World War II, in fact — the factory had been discharging methylmercury, which attacks the brain and the central nervous system, into Minamata Bay via Hyakken Harbor.

Minamata is situated on the beautiful Yatsushiro Sea, which is surrounded by the Kyushu mainland and several islands. The area was famous for the quality and variety of its seafood. Although the surface waters can get very warm in summer due to the mild and pleasant climate, cold, mineral-rich undersea springs of freshwater mingle at the bottom of the inlets and bays with the warmer saltwater, creating a marine environment very suitable for high-quality flounders and other flatfish.

My first Japanese mentor in creative writing, and the man most responsible for my settling where I have now long lived in Kurohime, Nagano Prefecture (because he settled here first), was the son of a doctor, born and raised in Minamata. Gan Tanigawa, the famous poet and critic, frequently boasted that the best fish in the world came from his home area. No small wonder that seafood was the major component of the people's diet.

The first patient recorded as presenting with what the textbooks now call Minamata disease was a child who was admitted to the Chisso company's hospital in 1956 with severe complaints such as the inability to talk, walk or eat. Soon, 54 more cases were admitted, and there were 17 deaths. As the disease spread, so the fear of a mysterious epidemic fomented that prejudice against sufferers and their families.

In 1959, professors from Kumamoto University made a formal announcement that the Minamata-area disease was a disease of the nervous system, caused by eating fish and shellfish from Minamata Bay. In their announcement they added: "Mercury has come to our attention as a likely cause of pollution in the fish and shellfish."

Although the Chisso company refuted this, experiments carried out on cats at the company hospital confirmed the suspicions.

A long, sad, disgraceful debacle followed, with countless protests and trials, all well documented. As an environmentalist, from afar in Canada I followed it as best I could, although every time I did so it stirred a helpless rage deep in my guts.

In 1970, when I was once again in Japan studying Japanese and fisheries (and when I first met Tanigawa), I started to hear rumors from Canada about a disease similar to Minamata disease affecting First Nations peoples in Ontario. Those people relied heavily on fish from the Wabigoon and English river systems for their livelihood.

It appeared that a company that had begun to operate a chloralkali plant there was using mercury cells dumping effluent into the rivers. Japanese doctors went to Ontario to compare notes and to study this Canadian outbreak of mercury poisoning.

Eventually, the Grassy Narrows and Whitedog First Nations sought compensation for loss of health, jobs and way of life. However, that legal quest is another long, sad, convoluted and highly disputational story — and the company responsible for the pollution closed down in 1976.

Mercury pollution is a worldwide and ongoing problem. Is there any hope? Can humanity learn from past mistakes?

Last month I was invited to Minamata to give the keynote lecture at a ceremony commemorating the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Minamata Disease Municipal Museum. That was my third visit to Minamata and I felt greatly honored.

The museum is set in a lovely park that is built on landfill that covered and contained the worst of the toxic sludge dredged from the bay. It is a place of ongoing research where the story of Minamata is laid out very clearly. It is also remarkable in that people who have suffered from the disease, and had their lives inexorably changed by it, regularly go there to talk to visitors and tell their stories. To hear these people is a very moving experience.

Monitoring for mercury pollution still continues in and around the area. From 1977 to 1988, a survey was conducted that involved testing the umbilical cords of 1,040 embryos and the hair of 288 infants for mercury. Based on those test results, in May 1990 it was declared that there was no longer any danger of infantile Minamata disease.

With the main source of pollution stopped and the toxic sludge contained, life seems to be returning to the seas around Minamata, where I was told corals, shellfish, fish and marine plants are thriving.

When I visited recently, my hosts again assured me that locally caught fish were safe to eat, so we enjoyed sashimi. Scenically the area is lovely, with a gentle sea (great for kayaking) in the near-landlocked bay surrounded by densely forested mountains and rolling hills.

Kyushu is a friendly place, and Minamata especially so. As might be expected, people there are very conscious of the environment and they actively promote clean industries, such as a plywood factory, recycling companies and so on. Also, a new Shinkansen bullet-train line opened in 2004, linking it with ease to Kagoshima in southern Kyushu and Hakata/Fukuoka — and then the whole of Honshu — in the north of the island.

It is a place I always want to go back to, and thankfully now with warmer memories.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.