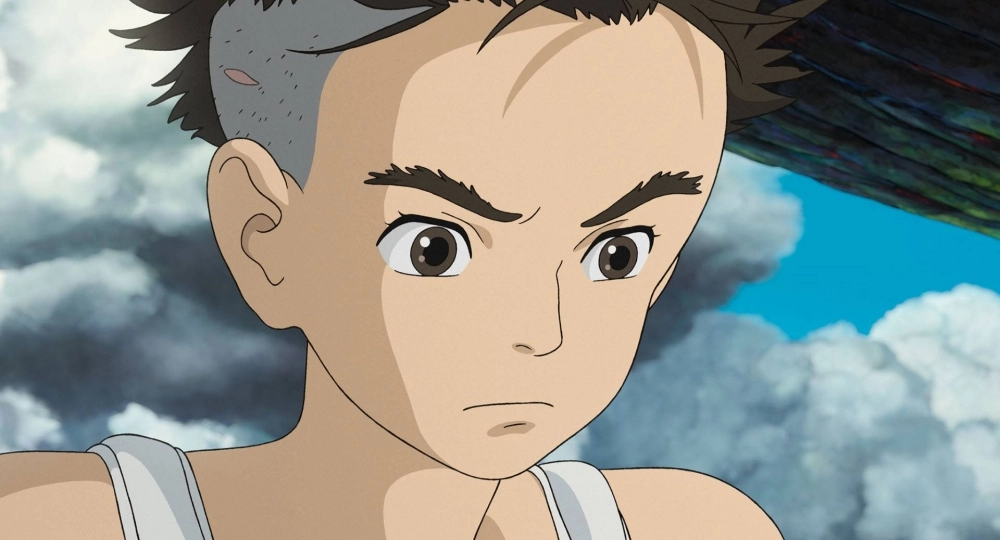

Many of the results from the 96th Academy Awards, such as the best picture win for “Oppenheimer,” had been widely predicted for weeks in advance. Not so for best animated feature, which analysts pegged as a toss-up between Hayao Miyazaki’s “The Boy and the Heron” and “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.” So when the latest film from the 83-year-old Japanese auteur was announced as the winner, even its biggest boosters were a bit surprised.

“I thought ‘Spider-Verse,’ with its distinctly contemporary and American preoccupations would be easier to approach and appreciate, especially among U.S. Academy voters,” says Susan Napier, author of “Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art.”

“‘Spider-Verse’ was huge in terms of box office, and is an incredible achievement in animation,” says David Jesteadt, president of GKids, which distributed “The Boy and the Heron” in North America and helped shepherd it to an Oscar nomination. Jesteadt, who was in attendance at the awards with several executives from Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki’s animation studio, calls the win “a beautiful moment.”

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.