At its essential level, art is a battle between the eye and the hand; the first representing sensory input, the second artistic habit and convention. When the hand outweighs the eye, art can become over-stylized, clichéd, and eventually dead. Asian art has been particularly prone to this; with young artists faithfully repeating the themes and styles of their masters in unbroken chains without looking far beyond.

This is evident throughout much of the history of Japanese art and also in the nihonga (Japanese-style painting) movement that emerged at the end of the 19th century with its famous mantra of "kachō fugetsu" (a term that uses the kanji for flower, bird, wind and moon) by which it limited itself to a narrow range of subjects treated in a classical manner.

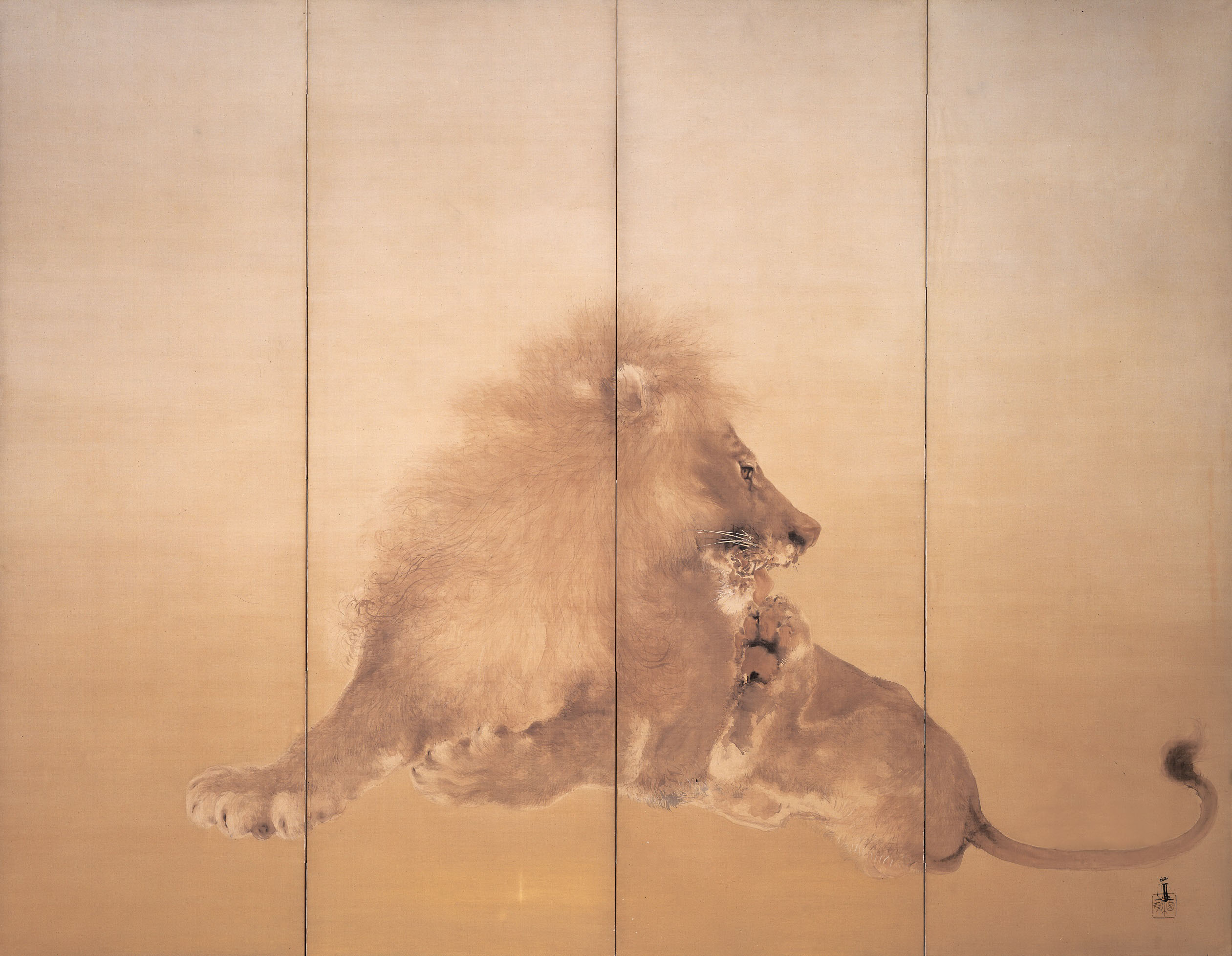

But, while the world of nihonga has often been guilty of blind veneration for artistic traditions, an exhibition of the works of Takeuchi Seiho (1864-1942) at the Museum of Modern Art Tokyo shows another side of the story, as the artist was a keen observer as well as an excellent brush man.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.