College students in China now face a daunting new reality: Their parents’ substantial investments in their education are less likely to translate into decent jobs upon graduation as the unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds in urban areas spikes in the post-COVID era.

The latest unemployment figures — a record 21.3% for the age group in June — have thrown a spotlight on this trend. Behind this number are the dashed dreams, increasing anxieties, readjustments of expectations and altered life paths of potentially millions of young Chinese.

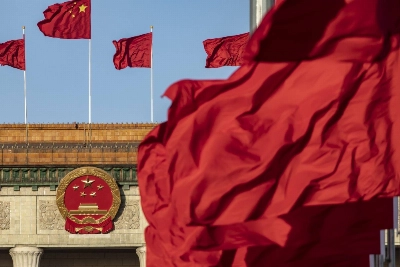

Last week, youth unemployment data for July was supposed to be announced together with other key figures in the country’s monthly economic activities report. But Beijing decided to halt the release of the data, citing “methodological optimization,” further fueling widespread data transparency concerns and heightening worries about the country’s economic slowdown.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.