It’s been a whirlwind two weeks for Anthony Albanese, Australia’s new prime minister.

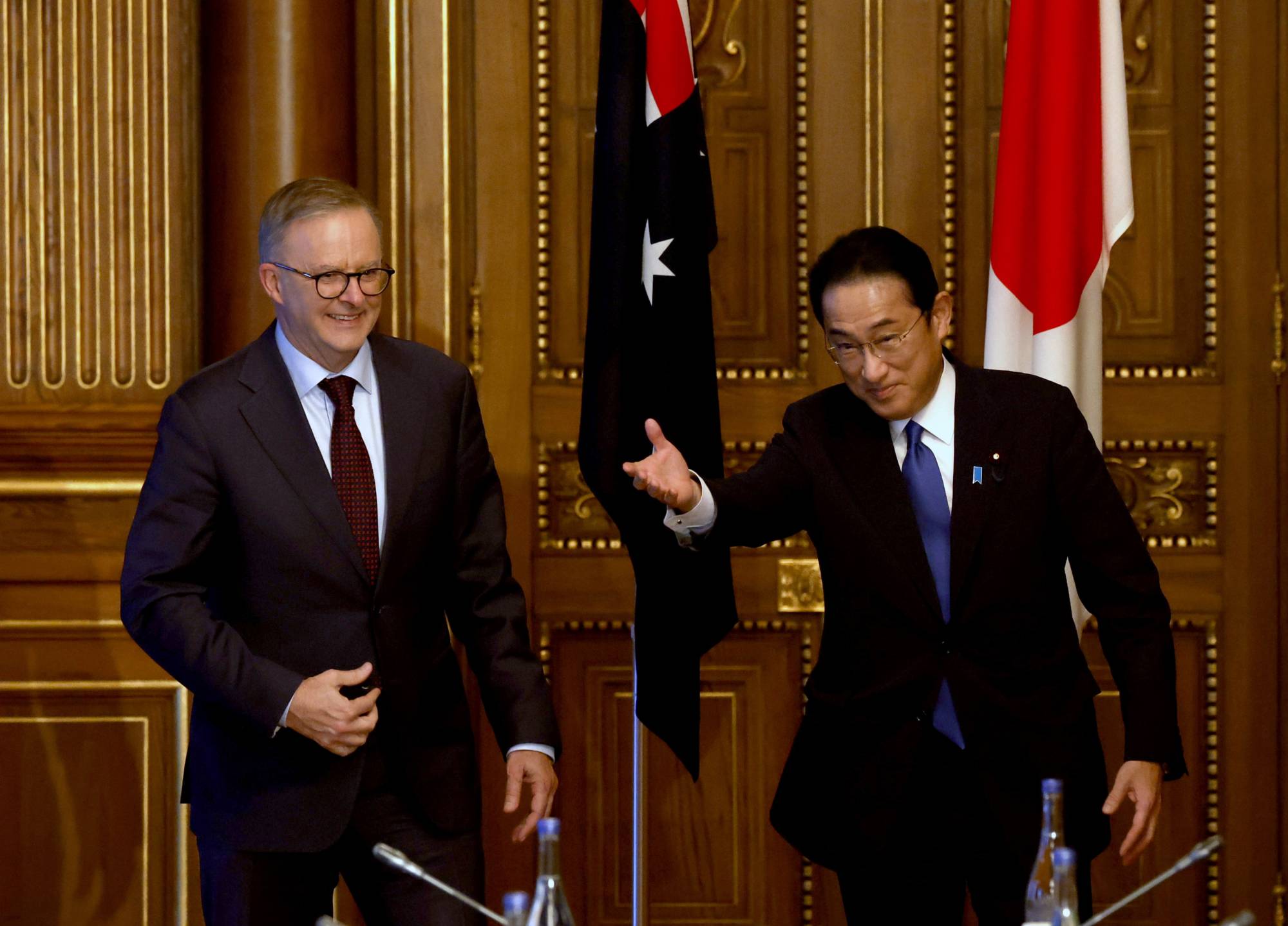

Just hours after he unseated incumbent Scott Morrison, he jetted off to Japan for meetings with Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and other world leaders. That visit sought to demonstrate the importance his government attached to Japan and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue — and foreign policy continuity in Canberra. While there will be some important shifts in Australian policy, they should facilitate still greater cooperation with Japan.

Albanese’s Australian Labor Party squeaked out a victory in last month’s ballot. As votes have trickled in, Labor is projected to hold at least 76 of the 150 Parliamentary seats, the minimum required to form a majority government. He may yet strike deals with smaller parties and independents on particular policies but an outright majority gives him some — but not much — room for maneuver.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.