Tucked away behind taller buildings on the southwestern side of Azabu Juban Station lies the small community of Koyamacho, a part of the Mita neighborhood in Tokyo's Minato Ward.

Or it did. The developers are moving fast, so by the time you read this, what little that remains of Koyamacho may well be gone.

A community that has existed for longer than any of us (it’s shown on a 1923 map of the city, lying within the boundaries of what was then Azabu Ward), Koyamacho still had, until quite recently, a tofu store, a dry cleaner, a handful of businesses and numerous houses — not to mention what was, in its heyday, apparently, a rather long-standing sentō bathhouse. Sources say the sentō dated back to the Taisho Era (1912-26), having used the same name and building up to its closure in recent years.

On a September walk through the area, some buildings still remained, but with notices of demolition pasted to their doors and windows, and marks left to indicate that the empty buildings had been checked over. Each was just as it had been before, only entirely devoid of life, waiting for the wrecking ball.

A real ghost town in the heart of Tokyo’s 23 wards. Now? Little more than cleared lots dotted with traffic cones, cranes and construction materials.

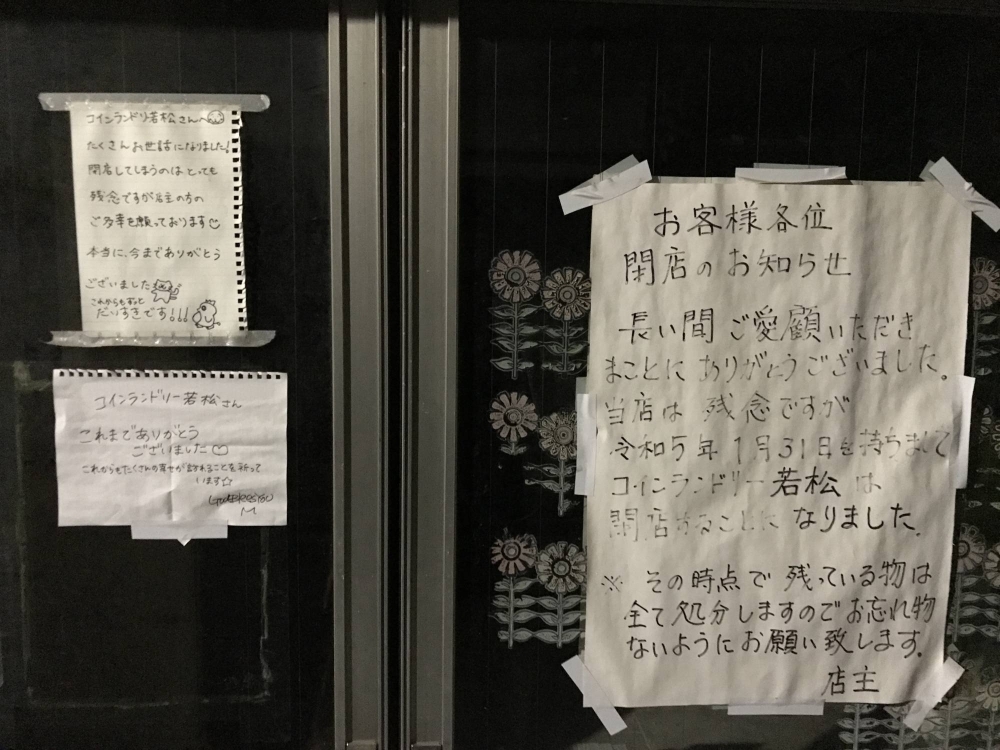

A few months ago, signs of what had been still clung to the empty buildings. The water utility and NHK badges adorned the doorways of wooden houses, intact shop signs still in place, and, in a rather touching gesture, letters of gratitude from former patrons pasted to the window of a coin laundry in response to the owner’s notice of closure.

So what’s behind it all? What will be replacing this little slice of a bygone Tokyo? Have a guess.

Of course — a gleaming 42-story residential edifice and two smaller residential blocks, along with office space, shops, a nursery school and a parking lot, no less. All scheduled to be completed by 2028, but with no coin laundry. No tofu shop. And presumably, given which part of the city we’re talking about, little to no affordable housing.

Money has to be amassed, people have to be housed, progress has to be made. But, like in many other parts of the capital, it comes at the cost of history, community and soul. A walk around any of these old neighborhoods is a walk through time and a chance to imagine a Japan of another era. But you’d better do it now before, like Koyamacho, they’re all gone.

In some countries, we’re spoiled for this sort of thing. In the village where I grew up in the United Kingdom, I could point out any number of buildings that are 100 years old or more. Most other villages in the vicinity are just the same. Even the U.K.’s cities, some of which underwent large-scale slum clearances, have still managed to retain an important slice of their past.

Not so in Japan, and certainly not so in Tokyo. Anything pre-Heisei Era (1989-2019) is disappearing fast, to be replaced with soulless glass towers that leave me feeling a little more empty down in the shadows below.

In the case of the Azabu Juban neighborhood and its surroundings, new buildings are popping up, ever higher, along the historic shōtengai (shopping street). Any trace of natural sunlight is fading fast, with the new Koyamacho development already dwarfed by the main monolith of the nearby Azabudai Hills project.

Adding yet another giant Mori “M” to the Tokyo skyline, the main tower is Japan’s highest building, having eclipsed the likes of Yokohama’s Landmark Tower and Osaka’s Abeno Harukas. Despite standing taller than the buildings around it, it manages somehow to look incredibly nondescript and, dare I say it, dull. This is perhaps because the area is already crowded with skyscrapers, unlike, say, Yokohama, where the Landmark Tower almost stands alone, looking over the city like a silent guardian.

But whereas the Landmark Tower lives up to its name as something of an icon for Yokohama, what structure in Tokyo can really be considered that kind of landmark now? Ten, 20 or 50 years ago, you’d have said Tokyo Tower. But with the famous red and white structure now standing just eight meters higher than Azabudai Hills’ Mori JP Tower and situated only a few blocks away, I’m not so sure.

Having safe, fit-for-purpose structures is absolutely crucial when planning the townscape, and the need to modernize is in our blood. But while the preservation of older history (think temples, shrines and other age-old sites) is vital, the death of Koyamacho shows that Japan as a whole desperately needs to begin preserving some parts of its modern history for future generations.